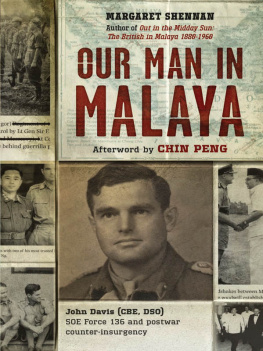

Pai Naa

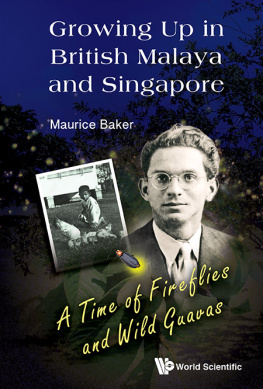

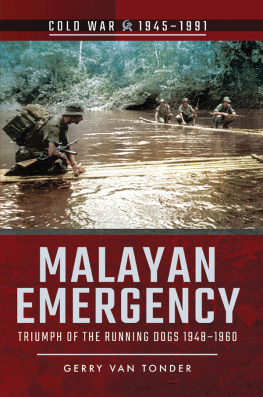

The true story of Englishwoman Nona Baker's survival in the Malayan jungle during WWII

Dorothy Thatcher and Robert Cross

Monsoon Books

Burrough on the Hill

Published in 2017

by Monsoon Books Ltd

www.monsoonbooks.co.uk

No.1 Duke of Windsor Suite, Burrough Court,

Burrough on the Hill, Leics. LE14 2QS, UK

First published in 1959 by Constable and Company Ltd.

ISBN (paperback): 9781912049066

ISBN (ebook): 9781912049073

CopyrightDorothy Thatcher and Robert Cross, 1959

The moral right of the authors has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Cover design by Cover Kitchen.

The publisher wishes to thank the families of Nona Baker and Robert Cross for their assistance with the publication of this book, in particular Caitlin Truman-Baker.

Contents

No more moving picture of jungle hardships has ever been painted than that in this book and no more authentic picture of Malayas Chinese guerrilla bandits. If it were fiction such an intensely vivid record of human endurance would be dismissed as quite incredible. But it is true.

Sir Richard Winstedt, K.B.E., C.M.G., F.B.A., D.LITT.

After living and fighting with the Chinese guerrillas for three years in the jungle near Kuantan, Pahang, Miss Nona Baker, the only English girl guerrilla in Malaya, has returned to civilization.

The Straits Times, 7 October 1945

MY FATHER, WHO was rector of Dunstable, had nine children and I was the youngest; having run out of names by then, my parents called me Nona, which was changed to Nin by my brothers and sisters. Coming at the end of a long line, I had to learn to fend for myself and I seemed to spend a large part of my early days wrestling on the nursery floor with the two brothers nearest to me in age; I have vivid memories of wriggling out from under a mass of flaying arms and legs. There was no rigid discipline in the rectory and, within reason, we were allowed to be as noisy and barbaric as we wanted: the exception to this was the stern rule that there must be complete peace in the neighbourhood of my fathers study.

I did not see much of my parents in the nursery days as they were both busy with parish work. I can remember standing on a chair by the nursery window, with the firelight dancing on the pale yellow wall, watching for a glimpse of my mothers scarlet cloak as she rounded the street corner on her way back from visiting the sick. My favourite occupation when I was allowed to see her in the evening was nestling up against her and breathing in the scent of violets, which always seemed to cling to her. My father spent long hours in his study, ostensibly writing sermons; he was a large, silent figure with a deep voice, and I found him rather frightening when I was young. Every morning he would summon the family to prayers in the dining room and, as we knelt down on these solemn occasions, I used to stare with fascination at the camels woven into the seats of the dining room chairs and count the steps on their humps.

Sometimes, when the tussles on the nursery floor became too hard to bear, the door would open and my eldest brother, Vin, would come in and rescue me from the fray.

I was a great favourite of his and he would spend hours playing with me when he was at home. He was seventeen years older than I and, a naturally big man being just over six foot with very broad shoulders, he seemed a giant to me in those days when he would sweep me up and carry me on his shoulder at an enormous height from the ground. I adored him and all my imaginary heroes and knights in shining armour were Vins in disguise. At this time he was studying at the Camborne School of Mines in Cornwall and was very seldom at home because even in the holidays he would be away in Wales or Cornwall studying mining, which had become his absorbing interest. When he left the School of Mines, he went to Australia and, to my sorrow, I did not see him for over ten years, but I never forgot my childhood picture of him as my hero and protector.

The rectory was a long low house with a corridor on the first floor, which ran the full length of the building. This long expanse of brown linoleum became a familiar route for me to the schoolroom, which was over the stables beyond the house and was reached by a bridge, which my father had built, connecting the two buildings. Each member of the family in turn had been taught by Miss Whitworth, our governess, who was such a good teacher that she had no difficulty in filling the schoolroom to capacity with other children from Dunstable as we grew up and went to boarding schools. A complicated system of hot-water pipes, which gurgled and rumbled alarmingly from time to time, kept the schoolroom warm in winter; the water was heated by an ancient stove in a small, dark, cave-like room, known as Readings cubby-hole, near the stables below, where the old gardener cleaned the knives and shoes. Reading hoarded there an amazing collection of odds and ends, which he was convinced would come in handy sometime, and he drowsed there over a succulent pipe when the bitter weather drove him to take refuge.

In the holidays the house was full to bursting as the headmaster of the local grammar school and my uncle, a housemaster at Fettes, used to send boys to us, often of various nationalities including Austrian and Chinese, whose parents lived abroad. Among our favourite activities was hiding in a sycamore tree whose branches spread out over the pavement, and waiting for the policeman to pass underneath on his way to point duty, so that we could drop stones on the silver top of his helmet. In the stables the remains of my grandfathers old carriage were kept, and another game of ours was climbing in and out of it and jumping up and down until it was a wonder it did not disintegrate into a thousand pieces. When I was five, my two younger brothers went away to Kings College Choir School and I was left alone: it was never quite the same again after that, as even during the holidays they preferred to ignore their baby sister, who could not possibly understand their games: either I spent a great deal of time hammering on the schoolroom door for admittance or, as a great favour, I might be allowed to count out nuts and bolts for their Meccano constructions. Sometimes when they were feeling bored with playing together, they would turn to me to help amuse them. In this way they taught me to ride a bicycle on the lawn at the back of the rectory, and to make sure that my training was complete they would spring surprises on me: on one occasion a garden roller was suddenly dragged across my path and, swerving to miss it, I rode straight through the plate-glass window of my fathers study. Fortunately he was too surprised to be angry.

One of my sisters had died at boarding school and my parents decided that I should be educated entirely at home; as most of my brothers and sisters were away, I began to see much more of my parents and grew closer to them, and when two of my brothers were killed in the first war, I felt something of their anxiety and sorrow. My father would take me for long walks through the parish and beyond, and I soon ceased to be frightened by the silences, which prevailed in his company; if I asked him a question, he would often take so long to reply that I had forgotten what I had said in the first place. One of his great interests outside the Church was in the bloodstock world, and it was impossible to mention a racehorse of any note whose pedigree he did not know off by heart.