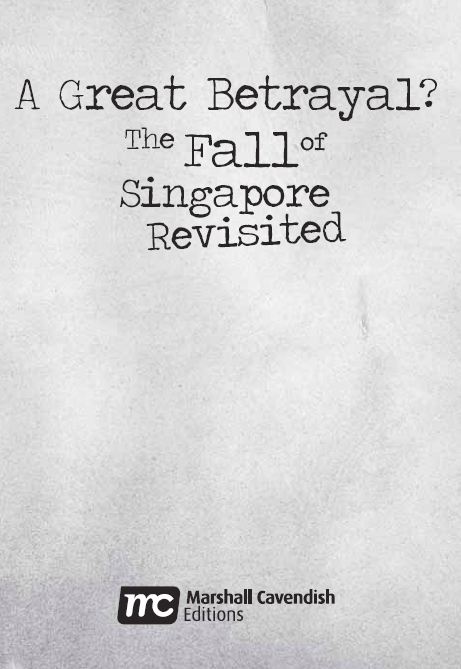

2010 Marshall Cavendish International (Asia) Pte Ltd

Published by Marshall Cavendish Editions

An imprint of Marshall Cavendish International

Times Centre, 1 New Industrial Road, Singapore 536196

Tel: (65) 6213 9300 Fax: (65) 6285 4871

E-mail:

Online bookstore: www.marshallcavendish.com/genref

Cover design: Rachel Chen

Marshall Cavendish is a trademark of Times Publishing Limited

Other Marshall Cavendish Offices

Marshall Cavendish Ltd. PO Box 65829, London EC1P 1NY Marshall Cavendish Corporation. 99 White Plains Road, Tarrytown NY 10591-9001, USA Marshall Cavendish International (Thailand) Co Ltd. 253 Asoke, 12th Flr, Sukhumvit 21 Road, Klongtoey Nua, Wattana, Bangkok 10110, Thailand Marshall Cavendish (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd, Times Subang, Lot 46, Subang Hi-Tech Industrial Park, Batu Tiga, 40000 Shah Alam, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Requests for permission should be addressed to the publisher.

National Library Board Singapore Cataloguing in Publication Data

A great betrayal? : the fall of Singapore revisited / edited by Brian Farrell and Sandy Hunter. Singapore : Marshall Cavendish Editions, c2009.

p. cm.

Includes index.

eISBN : 978 981 4435 46 8

1. World War, 1939-1945 Campaigns Singapore. 2. World War, 1939-1945 Campaigns Malay Peninsula. 3. Singapore History Siege, 1942. I. Farrell, Brian P. (Brian Padair), 1960- II. Hunter, Sandy, 1939

D767.55

940.5425 -- dc22 OCN462535579

Printed in Singapore by Times Printers Pte Ltd

The editors wish to thank Marshall Cavendish for proposing to rework and reissue this book to make it available to a wider readership, as well as their colleagues and contributors for making their essays available for that purpose. Particular thanks go to Melvin Neo for his vision and support for the project, Cheryl Sim for project management and indexing, and Rachel Chen for the striking cover. The Imperial War Museum kindly granted permission to reuse the photographs included in the book. Lt.-General John Coates (retired) kindly granted permission to use the excellent maps reproduced on pages 179 and 203, drawn from his seminal work Australian Centenary History of Defence Volume VII: An Atlas of Australias Wars, Oxford University Press, 2001. NUS Press agreed to host the endnotes for the book on their server, preserving them for interested readers, for which we are grateful.

GREAT EVENTS do not always have great drama, nor great participants. This can not however be said about the fall of Singapore to the Japanese in 1942. The most famous Briton of the last century, Winston Churchill, did more than anyone else to place a label on that eventover which he presidedthat still shapes how it is perceived. The fall of Singapore in February 1942 was, to the hard-pressed Prime Minister, the greatest disaster in British military history.1 That perception is one of two enduring things about the fall of Singapore. The other is apparently endless controversy. Controversy over how it happened, why it happened, above all whose fault it was. But around those two fixed points, our understanding of this seminal event of the Second World War and the twentieth century has been anything but static.

People from a dozen modern states were directly involved in the fall of Singapore: the United Kingdom, Japan, Australia, India, Pakistan, Nepal, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Indonesia, China, and above all Malaysia and Singapore. Perspectives on the event have been as numerous. From Churchills greatest disaster came the response by some Australians that it was a great betrayal. To the Japanese it was a great victory, but one certainly overshadowed by all that followed. To Singapore, it remains a defining moment in national memory. The verdict of scholars extended as far as calling it the battle that changed the world.2 In February 2002, the Department of History at the National University of Singapore hosted an international conference of historians to bring together scholars, students and veterans, to reflect on the ongoing controversies surrounding the fall of Singapore and learn from each other. The conference was held from 15 through 17 February, coinciding with the anniversary of the end of the campaign and the Allied surrender of Singapore Island. The venue, the university campus, was itselfappropriately enoughthe site of the one of the last significant engagements in the campaign. More than 600 people of all ages, from many nationalities, ranging in age from 15 to 85, heard papers presented by historians from Singapore, the United Kingdom, Japan, Australia, Canada and the U.S.A. on various topics related to the central theme: Sixty Years On: The Fall of Singapore Revisited, in the largest such gathering of scholars ever devoted to this subject. The theme had a special focus, one influenced by the large literature on the event published after the waritself influenced by what happened during the rest of the war. For most participants, the experience of captivity or occupation under the Japanese lasted a great deal longer than the campaign, and made a deeper impression. While that is understandable, it was time, we thought, to look again at the problem of how and why these people became captives or occupied in the first place. The conference was oriented around these questions: why and how did war come to Malaya and Singapore? Why did they fall as and when they did?

The book you are now reading first appeared in a different edition, in late 2002, as the published proceedings of that conference in Singapore. The conference was an attempt to pull together reassessments of arguments of very long standing about major issues such as the Singapore strategy, with fresh contributions to our knowledge such as a discussion of how Japanese soldiers experienced the fighting on Singapore Island. The objective was to provide a well-rounded, state of the art discussion of the central issues, and some of the shadows, relating to the fall of Singapore. The book met this objective, influencing a wave of publications that appeared in 2005 to coincide with the anniversary of the end of the Second World Warincluding my own volume The Defence and Fall of Singapore 1940-1942as well as appearing on reading lists at both staff colleges and civilian undergraduate courses in military history. It was influential enough to prompt the publishers to decide to reach out to a wider audience by releasing this revised edition, which focuses more directly on the event in question rather than working through the prism of the conference that spawned the collection of essays.

The trail followed by scholars trying to understand the fall of Singapore was in fact laid out in full, albeit in secret, by some of those responsible for it. In a secret session of Parliament in April 1942, Prime Minister Churchill intimated that when the dust settled and time was less pressing, an official inquiry would be held regarding the causes of the loss of Singapore. This was never done. Official papers retained for 50 rather than the customary 30 years by the National Archives in London reveal why. In January 1946 that wartime speech by Churchill, by now Leader of the Opposition, was published in a collected volume of speeches. This prompted a query by the Australian government, which in turn prodded now Prime Minister Clement Attlee to direct his military advisers, the Chiefs of Staff, to examine whether or not it was in the public interest to hold such an inquiry. They in turn passed the task on to their Joint Planning Staff, who in due course advised against an inquiry. Their argument laid out the broad trails scholars have pursued ever since:

Next page