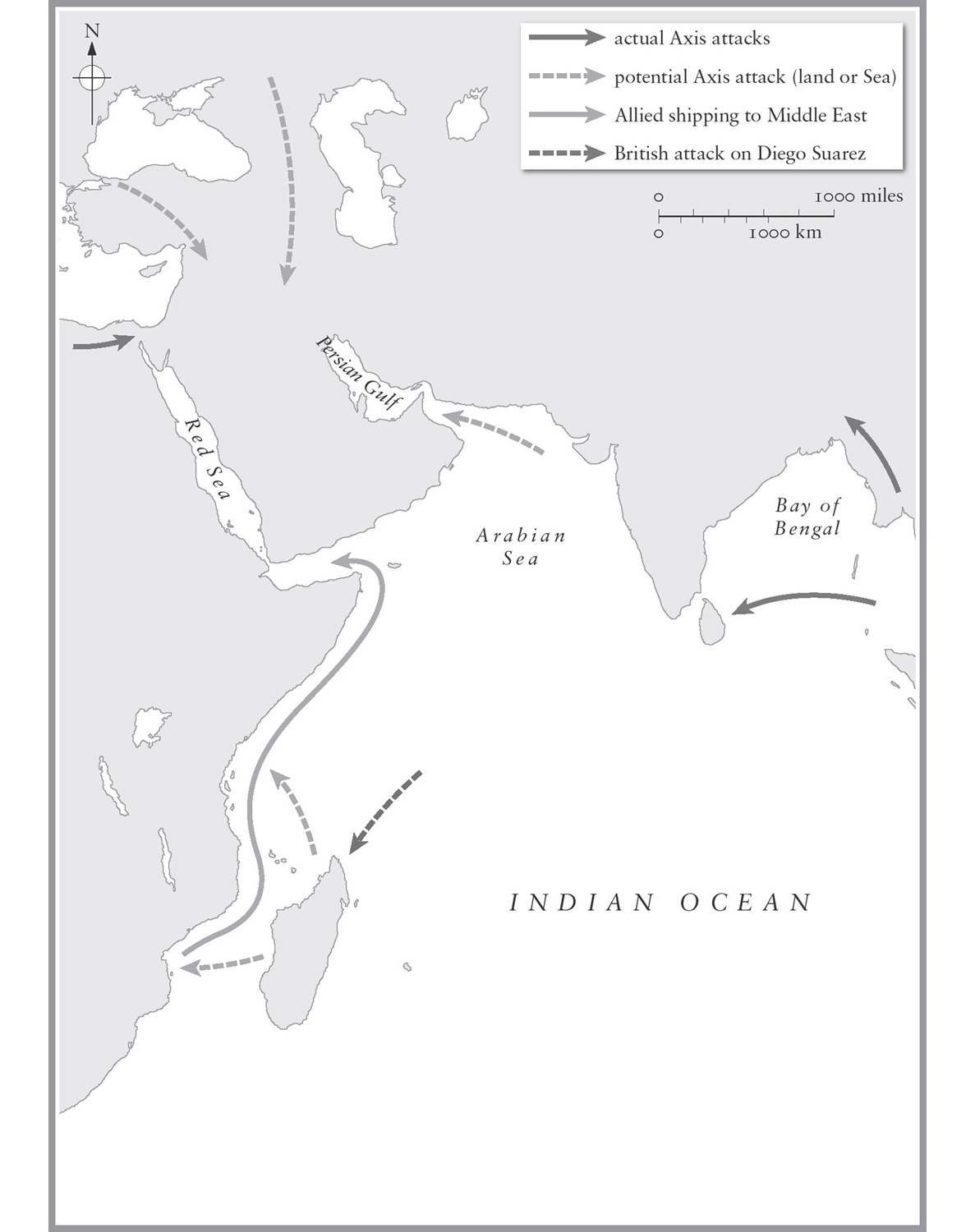

2. The Indian Ocean and the Middle East, 1942

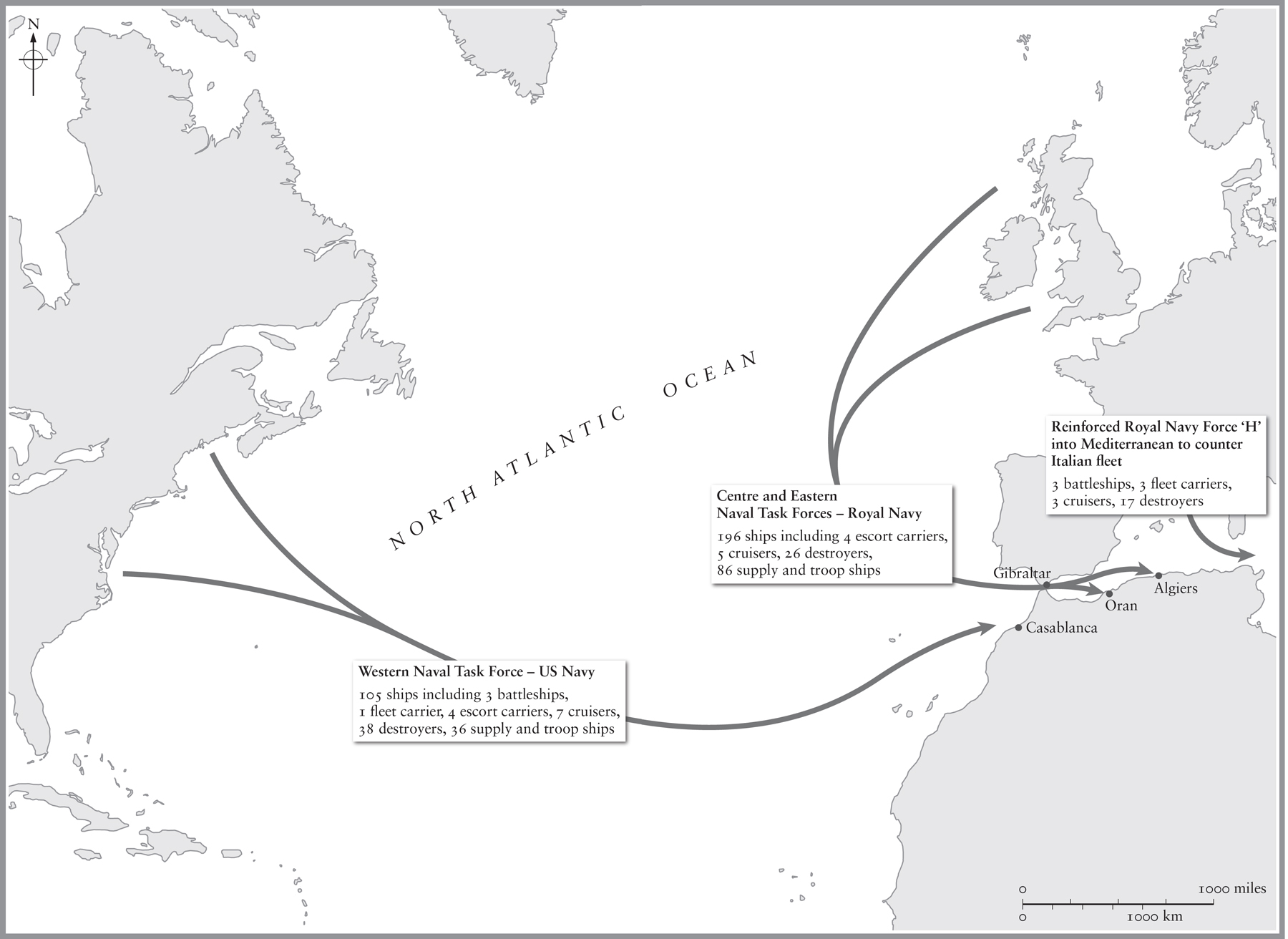

3. Movement of Naval Forces to Launch Torch Invasion, OctoberNovember 1942

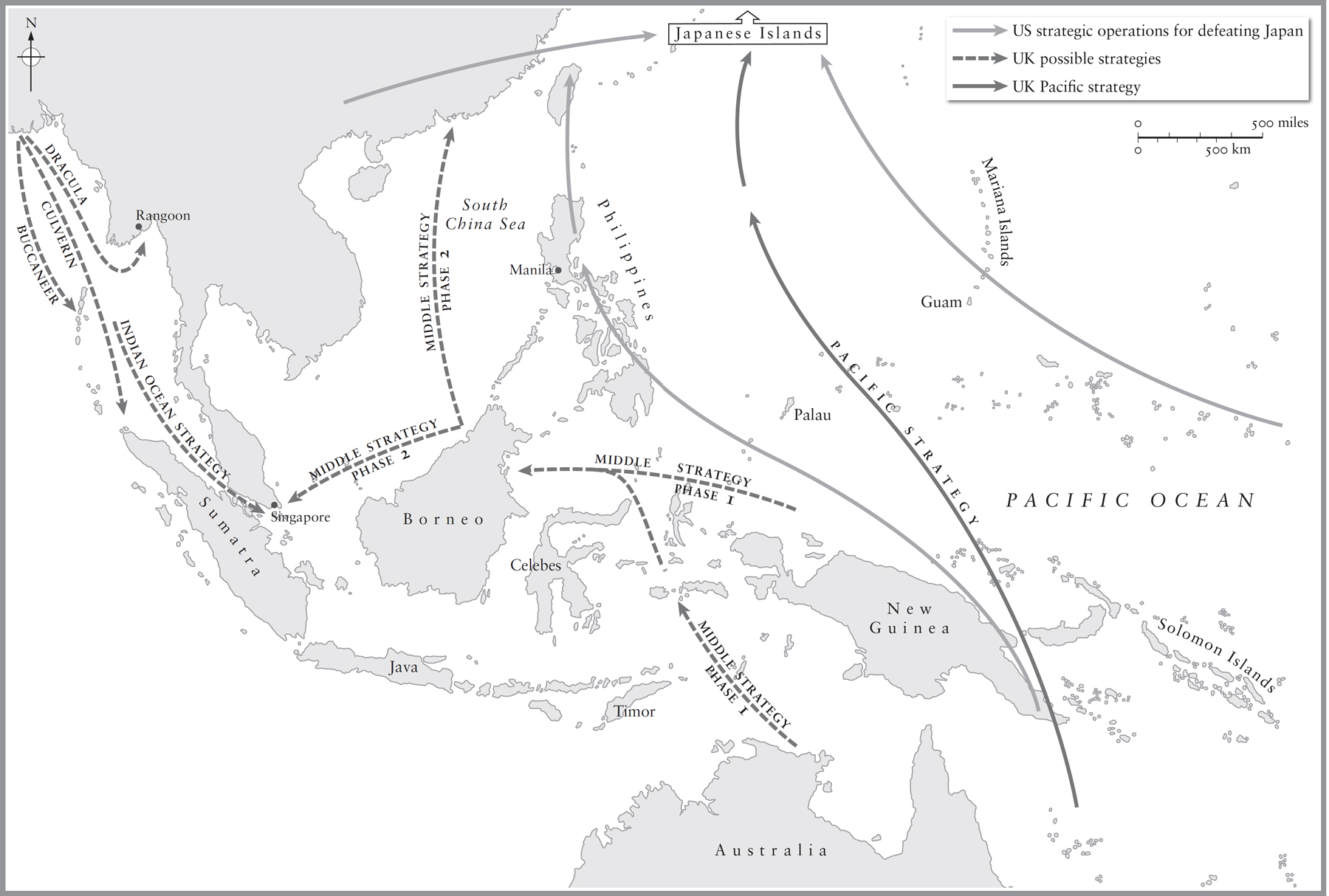

4. British Strategic Options in Southeast Asia/Pacific, 1944

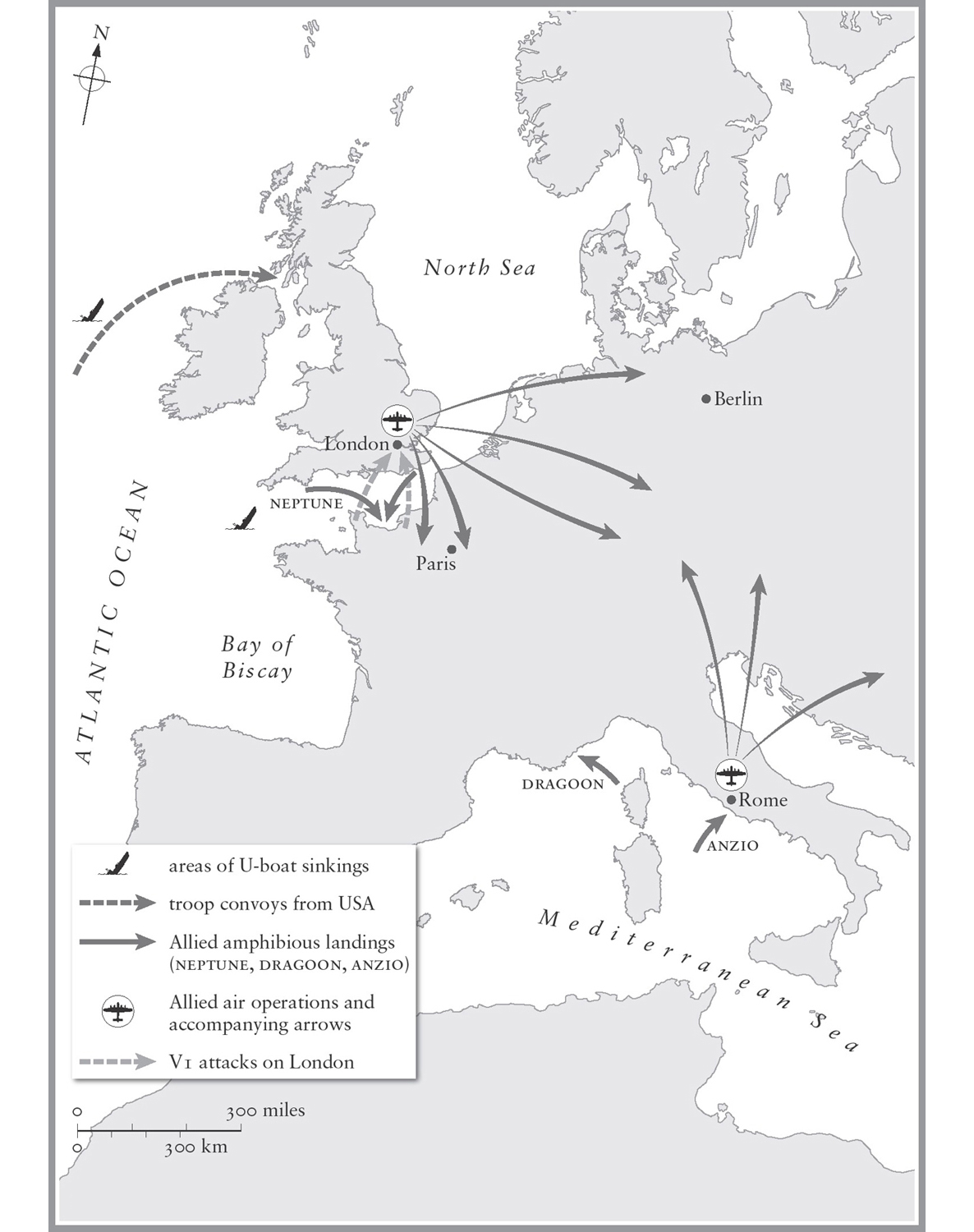

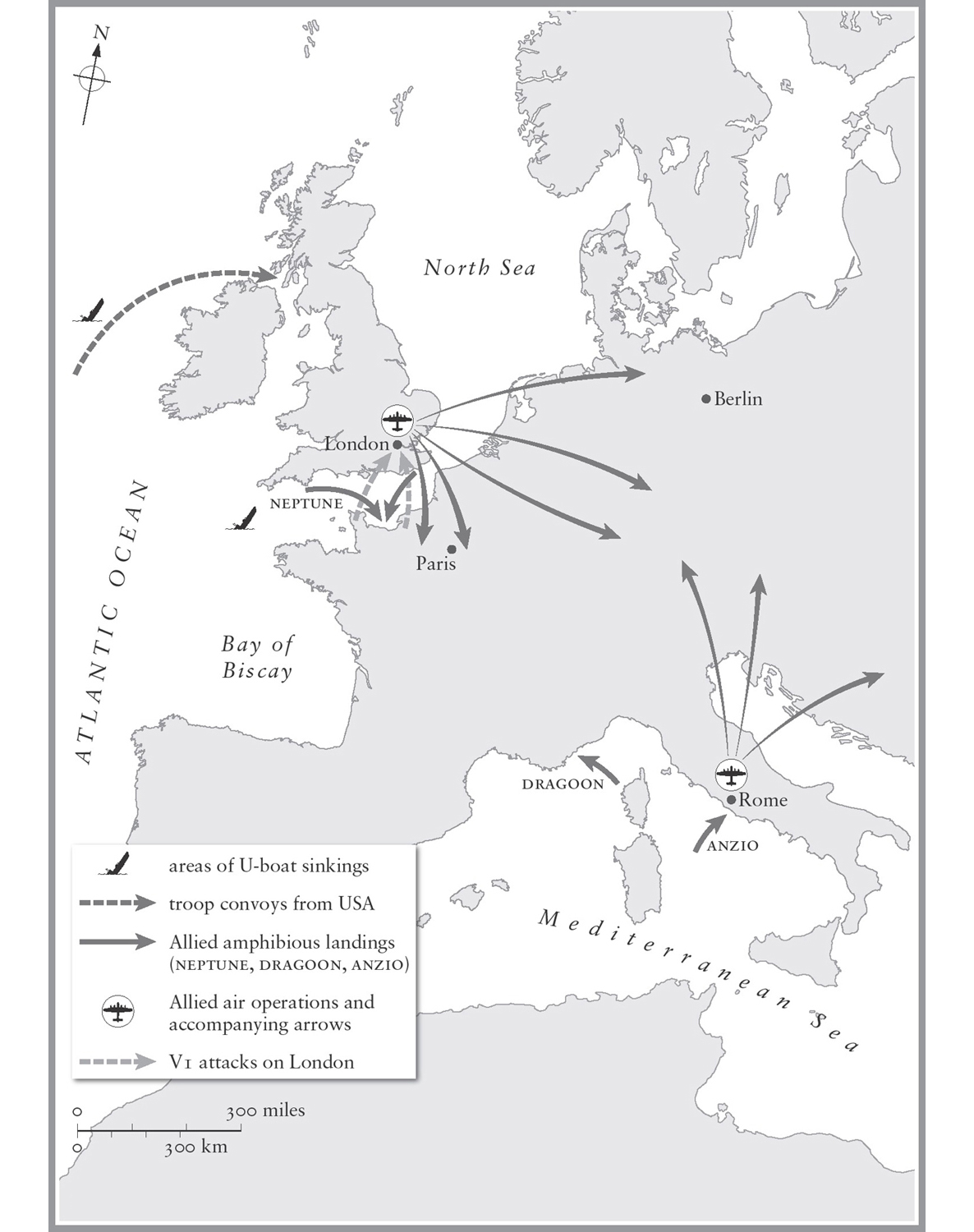

5. The Battle for Western Europe, JanuaryAugust 1944

This is a book about how Britain fought, endured and won a total war, what it cost (and to whom), and how the country emerged into a much changed world a very different place. It covers the period from the fall of Singapore in 1942 until the first negotiations over Marshall Aid in 1947. Like the previous book in this duet, Into Battle, this one combines military, political, economic and social history to help explain not only why events took the course they did, but how they were represented and understood at the time. They are the first books to offer the total history that the war, and its continuing place in the national discourse, deserves.

Like its predecessor, this book takes an essentially chronological approach to the war. This is not simply a narrative device, but a means to convey a fundamental point. Wars have their own dynamic, and they change as they go on. Britains Second World War changed more than most. This was obviously true strategically, as the European conflict that began in 1939 merged with its Asian counterpart and became a truly global war from December 1941. It was true in terms of weaponry, with the final campaigns fought with a new generation of munitions brought into being during the war, including, crucially, the atomic bomb. But it was also true in terms of attitudes and experiences. Responses to military conscription, for example, the extent of rationing on the British home front and the way in which the war was reported on the radio, all changed between 1939 and 1945. The way the conflict itself was understood was reconfigured during its last year, thanks to the rapid increase in British military casualties, the liberation of the concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen, and a growing sense of resentment at the rise of American power.

Wartime was not, therefore, an invariant condition. Understanding that helps us to appreciate the contingency of events that, in retrospect, seem so inevitable that they often determine how the history of the war is told. One obvious example is the general election of 1945, knowledge of the outcome of which has traditionally structured much of the political history of Britain during the war. Another one, even more important, was the question of when exactly the wars against Germany and Japan would end. Significantly, the end result of the conflict was known from a comparatively early stage. In this war, as in the previous one, the overwhelming majority of British people always expected they were going to win a crucial but often overlooked element in maintaining morale. In notable contrast to 191718, however, from the end of 1942 (and arguably earlier) there was no real sense of national jeopardy among leaders or populace that the enemy might stage a last-minute comeback. It was what would come next that was the problem. Determined to preserve as much national power as possible but looking forward with apprehension to what they knew would be a very difficult period after the war, British leaders tried to judge the moment and extent of maximum mobilization and the timing of the reconversion to a civilian economy. The unexpectedly drawn out defence of Germany after September 1944 posed some problems for this process, but not as many as the unexpectedly rapid defeat of Japan in summer 1945.

A history of the war that ended with VJ Day would be incomplete. Most of the significant consequences of the war for the UK were resolved only after August 1945, and the conflict itself endured in the absence of still-to-be demobilized soldiers, in the violence arcing across Southeast Asia and the movement of displaced persons throughout Europe, and in the rationed austerity that continued to define British civilian life. To understand what had happened, we need to look forward to the point where the confusion had begun to clear, and the new Britain that would emerge from the conflict had become apparent.

As that suggests, this books structure is determined in part by its arguments. It is divided into four parts, each focused on a different period of the war. the focus on the security of the Indian Ocean and Middle East. This was a much more immediate and concrete concern that had to be balanced against the alliance shadow play of potential cross-Channel operations. Bearing in mind how early ideas about post-war reconstruction took root in Britain, and how much contemporaries wanted a positive vision of what they were fighting for, I argue that Churchill missed an important trick in the summer of 1942. His unwillingness to engage with the political difficulties of the post-war world meant that he did not take the opportunity to seize control of the narrative around reconstruction, with long-term consequences for his party. It is impossible to imagine David Lloyd George, his First World War predecessor, committing the same error.