The truth is that there is no pure race and that to make politics depend upon ethnographic analysis is to surrender it to a chimera.

Ernst Renan, What is a Nation? (1882)

A nation is like a fish. If we are merdeka [independent] we can enjoy the whole fish head, body and tail. At the moment, we are only getting its head and bones.

Sutan Jenain, Indonesian nationalist

This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe that keeps piling ruin upon ruin and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

Walter Benjamin, Ninth Thesis on the Philosophy of History

I am hampered by ignorance of conditions of the past.

Sir Harold MacMichael, Kings Special Representative to Malaya, 1945

CONTENTS

A Guide to Further Reading

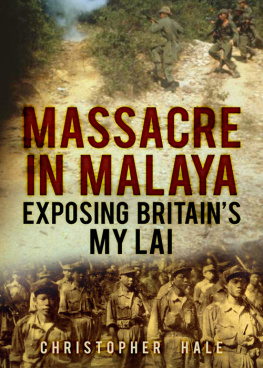

I first visited Malaysia at the end of the last century when I climbed Mount Kinabalu in Sabah on the island of Borneo to make a documentary film for Channel 4 television about Lows Gully, The Abyss. I returned in 2007 to make a documentary for National Geographic (Asia) about the coronation of the new Yang di-Pertuan Agong that would be broadcast as Becoming a King. I wanted to understand this fascinating and in many ways deceptive Southeast Asian nation that our colonial forebears did so much to shape. This book should be regarded as an extended essay rather than a textbook or academic historical study. For that reason I have not encumbered the text with a blizzard of reference numbers and have made minimal use of footnotes. I thank Peter Robinson for encouraging and refining the project at an early stage. I must acknowledge a number of books that profoundly influenced and informed my account of Southeast Asian history and the Malayan Emergency. Benedict Andersons classic study of nationalism Imagined Communities (first published in 1983) opened up the vista of political thinking in Southeast Asia. Andersons brilliant essays on Southeast Asian history and culture in The Spectre of Comparisons: Nationalism, Southeast Asia and the World (1998) and Under Three Flags (2005) offer dazzling insights into the nature of Asian political thought. Anyone writing about the Japanese occupation of Southeast Asia and its aftermaths must acknowledge a huge debt to Forgotten Armies (2004) and Forgotten Wars (2007) by Christopher Bayly and Tim Harper. Harpers earlier academic study The End of Empire and the Making of Malaya (1999) is rich with ideas. Anthony Stockwells edited collections of British Documents on the End of Empire: Malaya (3 volumes, 1995) and Malaysia: British Documents on End of Empire series (2004) proved invaluable. Cheah Boon Khengs Red Star over Malaya: Resistance and Social Conflict, During and After the Japanese Occupation of Malaya (1983), The Masked Comrades: A Study of the Communist United Front in Malaya, 194548 (1983) and Malaysia: The Making of a Nation (2002) are classic accounts by an important Malaysian historian. A groundbreaking study of the Emergency period is Kumar Ramakrishnas Emergency Propaganda: the Winning of Malayan Hearts and Minds (2002). Dr Ramakrishnas penetrating and subtle unpicking of how the British waged a war of ideas is an essential study. Ronald Spectors In the Ruins of Empire: The Japanese Surrender and the Battle for Postwar Asia (2007) provides a gripping account of the volcanic struggles that erupted across Southeast Asia in 1945. The work of Karl Hack, listed in the bibliography, had a profound influence on the development of the historical narrative in this book. Dr Hacks generous email correspondence, as well as snatched conversations at the National Archives in Kew and at the Royal Courts of Justice in May 2011, clarified many issues and opened intriguing new research pathways. I am grateful to Dr Andrew Mumford for sending me the manuscript of his important study The Counter-Insurgency Myth: The British Experience of Irregular Warfare. Mark Ravinder Frost was generous with his time and comments. I have tried to build on the pioneering research of Ian Ward and Norma Miraflor exposing the bloody events that took place at Batang Kali in December 1948, and published in Slaughter and Deception at Batang Kali. I am grateful to John Halford of the legal firm Bindmans and Quek Ngee Meng for responding to my many questions before and after the 2012 Batang Kali trial in London.

I thank Dr Yin Shao Loong, a brilliant young social historian and environmentalist and the esteemed Professor Farish Noor for endeavouring at least to put me right on the many aspects of Asian culture and history. I had many enlightening conversations with Gus and Enyd Fletcher. Tim Hatton corresponded with me about his visit to Batang Kali in December 1948.

I would like to thank Christopher Humphrey and Michele Schofield at AETN All Asia Networks, Singapore for permission to use extracts from interviews conducted for two History Channel (Asia) documentaries about the Emergency and the Japanese occupation of Malaya produced by Novista TV in Kuala Lumpur. I am especially grateful to Lara Ariffin, Harun Rahman and Tan Sri Kamarul Ariffin for such stimulating conversations and unstinting generosity over the last few years. It goes without saying that none of the authors or individuals mentioned here or in the bibliography bears any responsibility for factual mistakes in the text or advocates any of the views and opinions expressed herein. I am enormously grateful to David Robson for reading the manuscript and eliminating many infelicities of style and expression.

At the History Press I would like to thank Mark Beynon for his unstinting support, Lindsey Davis, Lauren Newby and our meticulous copy editor Richard Sheehan, who eliminated a number of howlers.

Readers are referred to my blog for more information and a selection of maps: http://malayanwars.blogspot.de

The Batang Kali Massacre of December 1948 took place not in the predominantly Malay town of that name but on on the Sungai Remok Estate, which is about 5 miles (8.29km) distant. Before 1957, Malaya was part of the British Empire but was never a unitary colony. British Malaya, the term used in this book, was a composite colonial territory that encompassed the Straits Settlements of Singapore, Penang and Malacca and a number of Malay sultanates in both the peninsula and northern Borneo. These were subdivided into federated and unfederated states. These Malay states were nominally ruled by sultans (or rulers) but governed as protectorates by the British through the appointment of Residents. The British imposed semi-centralised federal rule across Malaya after 1945 though Singapore remained administratively separate. In 1957, the British granted independence, or merdeka, to the Federation of Malaya. The British retained control of Singapore and Crown Colonies in northern Borneo Sabah and Sarawak. Kalimantan, the southern region of Borneo, was part of Indonesia. In 1963, Malaya was enlarged to include Singapore, for a short period, and the Borneo states of Sabah and Sarawak as the Federation of Malaysia. Singapore left or was ousted from the federation (depending on your point of view) in 1965. It is now an independent city republic. I have used Malayan to refer to all the non-European peoples (Malays, Indians and Chinese) of both colonial and independent Malaya who became Malaysians after 1963. It has been necessary, for reasons that will become clear to the reader, to refer to the Chinese, the Indians and the Malays. It would be wearisome to insert inverted commas for these catch-all terms throughout the text of this book but they are implied. Race was a pseudo-scientific idea imported to Asia by the European colonial powers and imposed through census operations and other administrative devices across a diverse ethnic landscape. Modern biology has shown that, in scientific terms, these old ideas of immutable racial differences can no longer be regarded as useful. There is some controversy about terminology used to refer to the indigenous people of the Malayan Peninsula. Aboriginal is a common term in anthropological publications and was used by the British during the colonial period but Orang Asli (meaning original people) is now preferred. Some regard the term aboriginal as confusing and derogatory. In the past, Malays referred to Sakai, which definitely is pejorative since it means slave. Throughout the book I have used the most accessible or familiar spellings of Chinese and Malay family and place names consistent with documentary sources. The history of currency in colonial Malaya is complex, as explained at http://moneymuseum.bnm.gov.my. In the text that follows dollars generally refers to Straits or Malayan dollars unless otherwise stated.

Next page