Contents

Guide

Pages

Foreword

....................

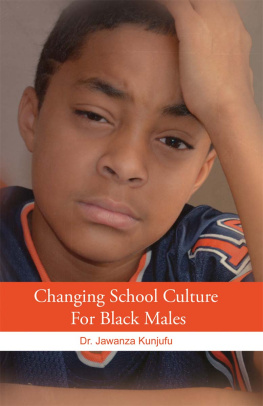

In America, Black and Latino males are overrepresented in categories typically associated with hardship and defeat. They experience disproportionately high rates of unemployment, incarceration, and homicide, and many of them are so disenfranchised (approximately 34 percent of Black males between the ages of 16 and 34) that they are literally "missing" from key census data because they are neither working, in school or college, or in the criminal justice system (Patterson, 2015).

In most schools and districts throughout the United States, Black, and in many cases Latino, males are overrepresented in educational categories typically associated with failure and subpar academic performancedropout and suspension rates, special education placements, and college readiness programs. However, on indicators associated with successenrollment in honors, gifted classes, and advanced placement courses, matriculation to college, and degree attainmentBlack and Latino males tend to be vastly underrepresented. With few exceptions, these dismal patterns are evident in urban, suburban, and rural school districts throughout the United Stateseven in communities with relatively small minority populations.

These patterns are pervasive throughout the United States, and they have been in place for many years. Rather than urgency, there is a profound and disturbing sense of resignation about our ability as a nation to counter these dismal trends.

Becoming the Educator They Need provides clear and practical guidance to educators and others on what can be done to support boys and young men of color. Drawing upon his life experience and his work as an educator and advisor to schools throughout the country, Jackson outlines strategies and practices that can be helpful in countering the negative trends and altering the life trajectories of young Black and Latino males.

For those in search of solutions and who seek to make a difference in the lives of young men, this book will be an insightful resource.

Pedro Noguera

August 2019

Introduction

....................

When I was 16 years old, my best friend, Tony Binion, was murdered. I remember how he laid there while people stood around staring intently at his body (which, at the insistence of the police, remained uncovered so as not to disturb the crime scene). I remember people, including family members and close friends, screaming and crying. We were so young. Neither of us had even begun to grow facial hair. Prior to the incident, Tony was at a party from which another young man, who was being disruptive, had been thrown out. After a time, the young man returned and began randomly shooting into a crowd of people, among them Tony and a few of his friends. As people scattered, Tony was shot in the chest and died at the scene.

The next morning, the headline on the front page of the newspaper read, "Shooting Victim, Good Kid," and a photo of Tony accompanied the article. I was sick to my stomach. Tears rolled down my face. The hurt I felt that day and after was excruciating. It seemed as though the rest of the world was able to move on, but my life stopped for a moment that day. This was not how Tony's and my story was supposed to end. Tony and I were going to be roommates in college, each other's best man at our weddings, and godfathers to each other's children. We had dreams of going to the prosTony to the NBA and me to the NFL. Like too many other young Black and Latino males, Tony's life was cut short before it could truly begin.

When I returned to school on the Tuesday following Tony's funeral, one of my teachers said something that fueled both my anger and my will to prove her wrong. She said that I was wasting my time [by coming back to school] because kids from my community didn't succeed in life. Her comment made it clear to me that she found no fulfillment in educating me. Her perception had become her reality. She was convinced that her implicit biases about young Latino males and young men who looked like me were right. I checked out of her class mentally for the remainder of that semester because I knew she didn't want me to succeed. I knew that she was just there to, as she would often state, "pass the time and get her paycheck."

When students know you don't care if they succeed, it's tough for them to focus and push themselves. I knew my teacher had her mind made up about the Black and Latino males in my class. When she interacted with us, she was distant, and when she spoke to us, it was only to scold us or make sarcastic comments. She didn't even try to hide her true feelings. I knew her perceptions of me were wrong, but as a 16-year-old with low self-esteem who was living in poverty, socially and economically disadvantaged, and living in a stressful situation at home in a violent neighborhood, I wondered if her opinion of me was right. However, regardless of her opinion of me, I wanted to be successful.

Fortunately, I also had teachers who supported and inspired me while growing up. The one I recall most fondly is my elementary teacherDr. Delores Sangster.

Mrs. Sangster exemplified discipline and accountability. She set high expectations for all her students, and my classmates and I understood that she expected us to do well. When we heard her heels clicking up the hallway, we immediately began to assess our behavior and adjust it accordingly. All talking ceased, and we would find our seats and sit at attention. Mrs. Sangster wasn't the one who you wanted to upset or disappoint by breaking the rules; there were consequences for that, and my classmates and I tried to avoid them at all cost.

One of my classmates, Glenn Dillard, and I just didn't get along with each other. We fought often, and Mrs. Sangster would take us into a small room and give us each three whacks with the paddle. (Mrs. Sangster's discipline was tougher than some of the hits that I took as a football player for 20 years). After she paddled me, she would always sit me down to talk. Though, with my bottom stinging, I had to struggle to focus and remain attentive; it was worth the effort because Mrs. Sangster would tell me how great I was and how much potential I had to be greater in life. She told me I was a success story waiting to happen. She saw the value in the fact that I loved to talk and told me that one day I would be speaking in front of thousands of people. Guess what? That's exactly what I do for a living today. Mrs. Sangster "spoke me" here.

Educators must use their words wisely because words affect students both positively and negatively. When students are coming from tough circumstances, a positive word can give them hope. Some of the young men in your class are extremely broken and need a positive voice.

When I was in elementary school, I was extremely hurt on most days. My stepfatherwho had been physically, verbally, and mentally abusive, would walk around our house for weeks and not say two words to me, but Mrs. Sangster both spoke to me and saw something in me. I didn't know or have a relationship with my biological father, whom I strongly resemble. Even though I at times didn't like who I was or know who I was, Mrs. Sangster called me a kingand meant it. She said it so often that one day I started to believe it. One day, a young man "called me out of my name," and I told him, "I don't care what you call me. Mrs. Sangster said I was a king." Her words resonated with me. She spoke positive words to me and my classmates every day; some of us received them and some of us dismissed them.