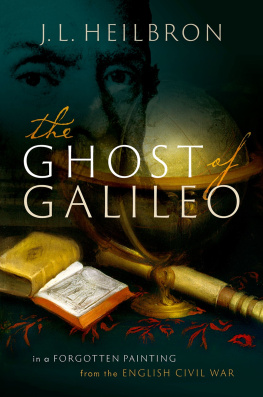

The Ghost of Galileo

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox 2 6 dp , United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

J.L. Heilbron 2021

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2021

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020938749

ISBN 9780198861300

ebook ISBN 9780192605559

Printed in Great Britain by

Bell & Bain Ltd., Glasgow

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Contents

It is a pleasure to thank my wife, Alison Browning, for her capital formative ideas, help in bibliography and transcription, and perfectly tempered enthusiasm; my friend and colleague Moti Feingold for the strength of his scholarship, gentleness of his corrections, and generosity in encouraging trespass into the fields he can call his own; and my editor at Oxford, Latha Menon, for her ever wise and informed advice. Since much of this book is composed of mosaics, I have a particular debt to those who have helped me to the quarries: compilers, indexers, librarians, archivists, and curators, and, among them, I must thank especially members of the staffs of the Bodleian Library in Oxford, the British Library in London, the Dorset History Centre in Dorchester, the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, and the National Trust at Kingston Lacy. Books may be written by their authors but are seldom produced by them. Among those at Oxford to whom I am indebted are Jenny Nuge and Guy Jackson, who coordinated the production, Debbie Protheroe, who gathered the high-resolution images, and Hilary Walford, whose impeccable copy-editing has removed inconsistencies in dates and format that proliferated during the decade this work has been under construction. Finally I must acknowledge the many friends who have listened to me describe the mystery of the painting that makes my story. Among them are Dan Kevles, Adriana Turpin, and the patient regulars at the Rose and Crown in Shilton, West Oxfordshire.

The age of hieroglyphs is not dead. Pictograms direct road traffic, point us to exits and toilets, and invigorate trademarks, logos, and the computer world. A little experience also makes familiar the emblems of nationhood (flags, anthems), professions (uniforms, insignia), religion (crucifix, star of David), other perils (skull and crossbones), sex (readers choice). With more knowledge, we can identify personifications of such abstractions as Justice (with her sword and scales), War (Mars), Love (Venus, Cupid), the Seven Liberal Arts, and the Five Senses. In early modern Europe, educated people who spent most of their quality time with ancient authors could read the iconography of the old myths and Bible stories as plain text. They understood the power of icons. Francis Bacon: Emblem reduceth conceits intellectual to images sensible, which strike the memory more.

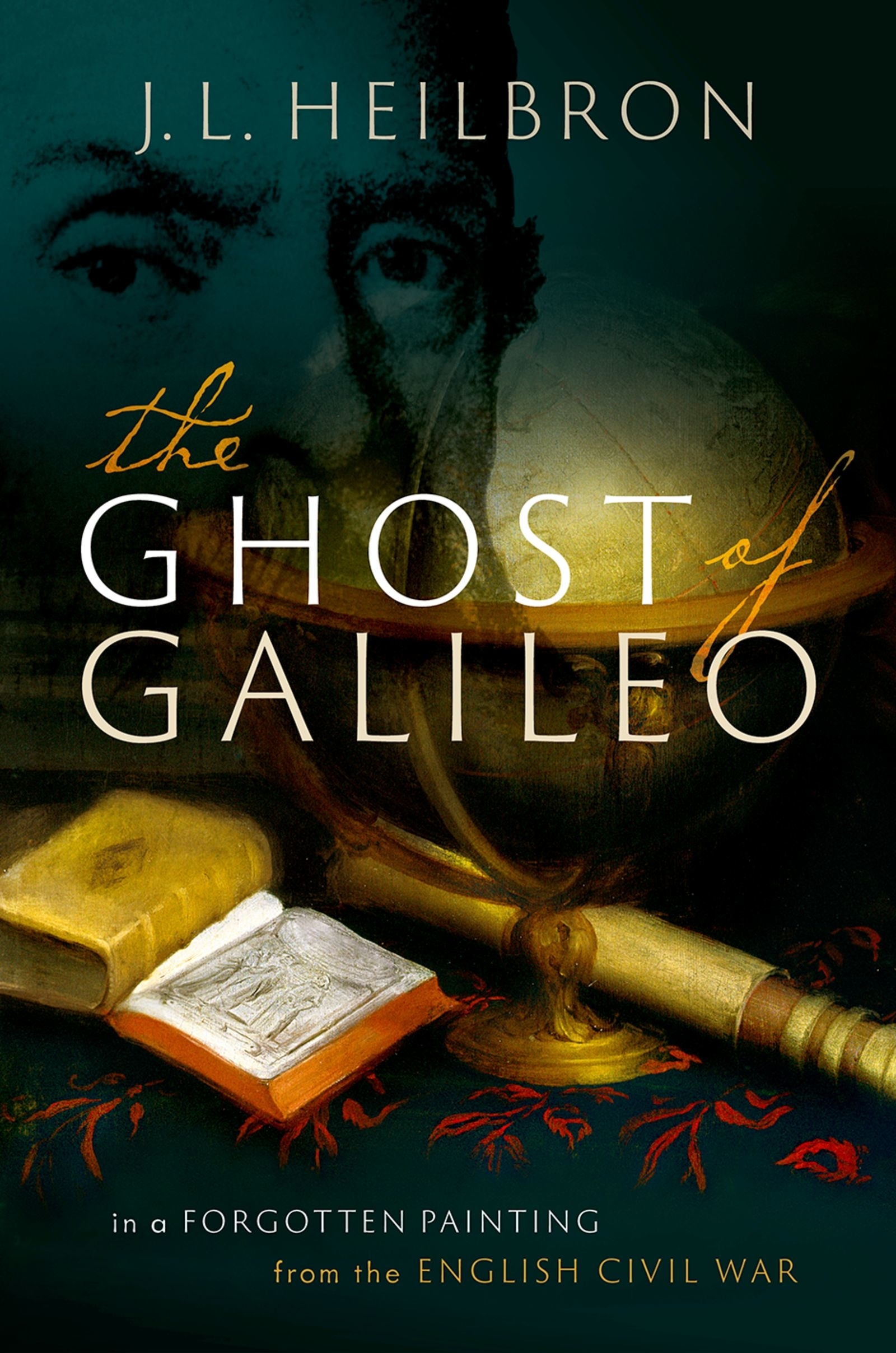

The hieroglyph whose elucidation frames this book hides in a painting made in Oxford in 16434. The painting presents the unhappy young heir of Corfe Castle, John Bankes, and his concerned tutor, Dr Maurice Williams (see ).

Figure 1 Francis Cleyn, Our Painting (1643/4): Dr Maurice Williams (standing, with hand on globe) and John Bankes.