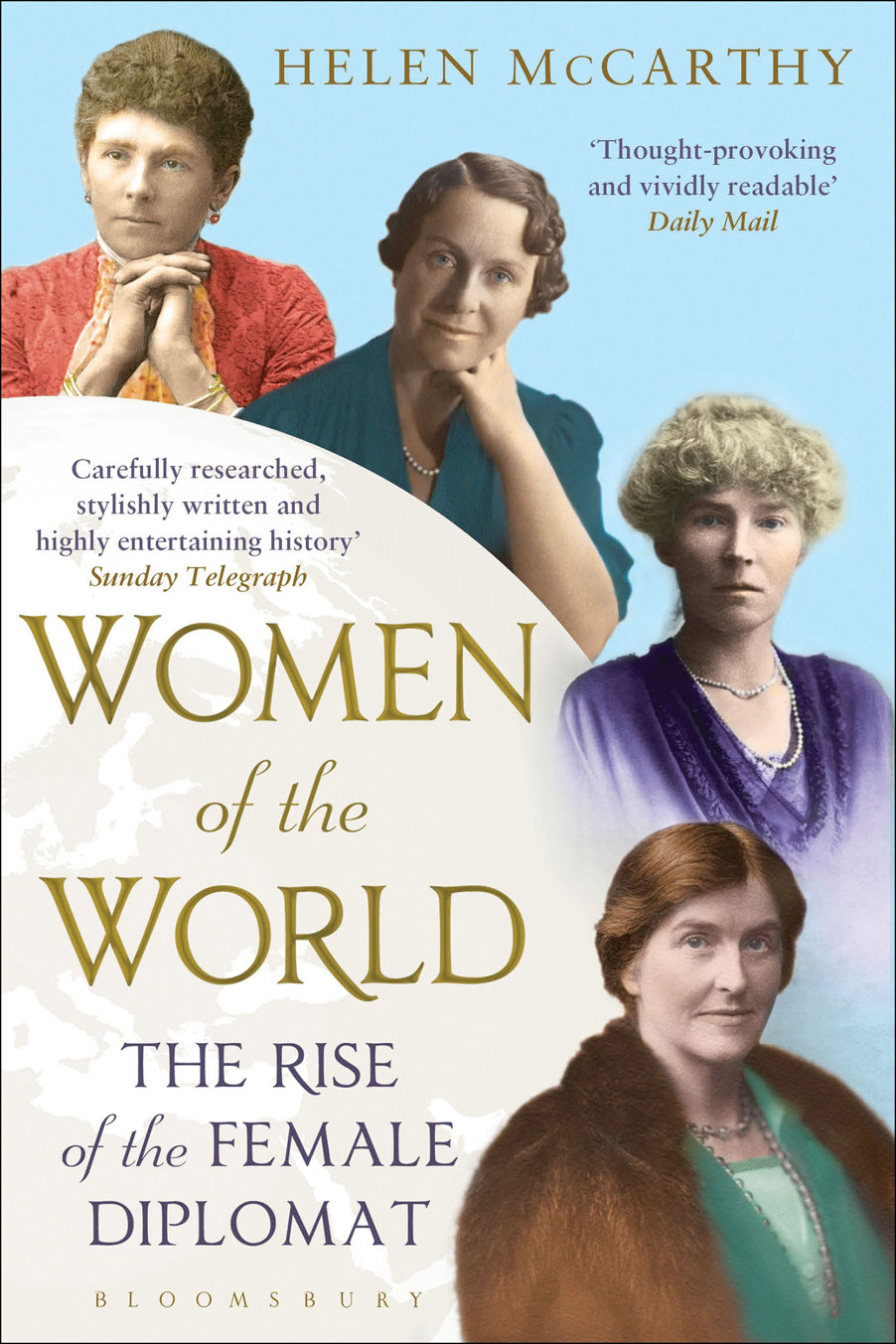

Helen McCarthy - Women of the World: The Rise of the Female Diplomat

Here you can read online Helen McCarthy - Women of the World: The Rise of the Female Diplomat full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2014, publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Women of the World: The Rise of the Female Diplomat

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Women of the World: The Rise of the Female Diplomat: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Women of the World: The Rise of the Female Diplomat" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Women of the World: The Rise of the Female Diplomat — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Women of the World: The Rise of the Female Diplomat" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

For James, Florence and Beatrice

One generally did not meet many diplomats growing up in a lower-middle-class family in suburban Essex. With its grammar schools, fine Norman castle and weekly roller disco, Colchester was as pleasant a place as any in which to pass ones childhood. But it was not frequented much by members of Her Majestys Diplomatic Service. I did not know anyone who knew a diplomat, and nor did any of my friends or relatives.

I was aware, of course, that such people existed. One read about them in novels and history books, or saw them in films and TV programmes, usually depicted as silver-tongued bullshitters or eccentric fools (Lord John Marbury, the unhinged British ambassador to Washington featured in The West Wing, is perhaps the perfect epitome of the latter). But I did not encounter my first real, flesh-and-blood British diplomat until after I had left university and was midway through a gloriously self-indulgent year attending classes at Harvards Kennedy School of Government. Included in the schools regular events programme was a series of seminars on the theme of contemporary diplomacy, one of which was addressed by a youngish British diplomat called Carne Ross from the UKs Permanent Mission to the United Nations in New York. His subject was the negotiations surrounding the drafting of an important Security Council Resolution concerning sanctions on Iraq. To be honest, I do not remember much about what was said; it seemed to hinge upon the placing of a comma in the crucial clause of the resolution. But I remember a great deal about Carne Ross. He was everything I expected a diplomat to be: handsome in an unflashy way (think Boden catalogue rather than Calvin Klein billboard); authoritative without being abrasive; principled but not pious; owner of an understated but unmistakeably steely intellect, and oh-so-slightly diffident in overall demeanour.

A few months later I attended another Kennedy School seminar, this one addressed by Carnes boss, Sir Jeremy Greenstock, then Britains ambassador to the UN. Again, the substance of his remarks eludes me (much talk of Britain punching above its weight I seem to recall), but Greenstocks elegant conversation loaded with silken vowels and lightly freighted with purring consonants only reinforced my growing conviction that Britains diplomatic corps were a really rather special breed.

And as if just to prove that diplomats are like buses (you spend a lifetime waiting for one and then three come along at once), soon after I found myself rather serendipitously invited to a function at the British embassy in Washington hosted by the then ambassador, Sir Christopher Meyer. As he addressed the assembled guests, Meyer struck me as rather more of a leg-puller than Greenstock or Ross, more of a hail-fellow-well-met kind of character, but no less impressive for it. As the sun set behind us on the embassy lawn and we were summoned to dinner by an immaculately dressed butler, I came to an important conclusion: diplomats were bloody brilliant people.

There was, nonetheless, no question of my ever becoming one. I had a terrible ear for languages and found travel outside the UK mildly stressful, even in Anglophile Massachusetts. I was, for instance, totally discombobulated by the discovery that ATMs in the US spit your cash out before theyve returned your card, a minor detail which I imagine anyone seriously cut out for diplomacy would take in their stride, but which for me became a near-daily reminder of my outsider status which I could never quite shrug off.

This low-key, rumbling sense of cultural alienation was a far greater deterrent to joining the Foreign Office than anything to do with being female, although I remember thinking at the time how it was almost certainly no coincidence that my first three contacts with the diplomatic world had all come in masculine form. The reasons, it seemed, were not difficult to fathom: the brash, macho world of politics was a pretty unkind place for women full stop; and diplomatic careers, with the endless string of overseas postings and round-the-clock entertaining, appeared to lie at the tougher end of the spectrum, particularly for women wishing to balance work with family life.

It was only some years later, while researching my doctorate on internationalism in the 1920s and 30s, that I began to reflect more deeply on the reasons behind womens historic under-representation within the diplomatic world. This, I discovered, was not simply a function of their traditional absorption in childrearing and homemaking; nor was it a straightforward analogue of the broader feminist struggle to win civil, political and economic equality. Womens admission to the diplomatic profession in Britain was not achieved until 1946, almost thirty years after the vote was won, and some twenty years after female candidates had become eligible for top grades of the Home Civil Service, as well as most other high-flying professions. Why so late? What was so special about the representation of national interests abroad that only men were believed capable of doing it? And what happened in 1946 to make the government change its mind?

As I mused upon these problems other questions presented themselves: were women really entirely absent from diplomacy before mid-century? Were there other ways in which they might have influenced foreign affairs, perhaps as wives, patrons or confidantes? And what about after the bar was lifted? How many women joined the Diplomatic Service in the post-war years? Who were they? How did they survive in what was hitherto an exclusively masculine profession? Did they shake things up or try to fit in with the existing culture? Has the presence of women changed the way diplomacy is done?

On further probing, I discovered that there was practically no existing research on this subject, save a few light-hearted books on diplomatic wives, some biographies of well-known figures such as Gertrude Bell and Freya Stark, and a preliminary research note produced by the Foreign Office back in the 1990s. This was despite the availability of an extraordinarily rich treasure trove of archival material personal papers, diaries and memoirs not to mention the as yet unrecorded testimony of those members of the post-war pioneer generation still living. Plenty of male diplomats had written their memoirs or set down their thoughts for posterity in interviews, but as for their female colleagues: one was met only with silence.

As a subject for a book, it seemed tantalising, but I foresaw problems. Was I the right woman for the job? I knew practically nothing about the history of diplomacy. I was not one of those scholars who could navigate the Foreign Office files housed at the National Archives in Kew as if it were their local supermarket. I had no personal connections to the Diplomatic Service, and could not tell a charg daffaires from a chef de protocol, let alone explain the difference between a memorandum and a minute. Yet on further reflection, it struck me that my outsider status could bring advantages, as I would be studying this intriguing, alluring world with fresh eyes and an open mind, free from any fixed notions of how diplomacy works, what diplomats do, or indeed how diplomatic history ought to be written. If that was not sufficient inducement, there was the additional knowledge that if I did not write this book, someone else eventually would a thought too awful to contemplate. So I decided to take a deep breath, muster my courage, and jump in. The result is Women of the World.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Women of the World: The Rise of the Female Diplomat»

Look at similar books to Women of the World: The Rise of the Female Diplomat. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Women of the World: The Rise of the Female Diplomat and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.