Copyright 2018 Alic ia Malone.

Published by Mango Publishing Group, a division of Mango Media Inc.

Cover and Layout Design: Elina Diaz

Mango is an active supporter of authors rights to free speech and artistic expression in their books. The purpose of copyright is to encourage authors to produce exceptional works that enrich our culture and our ope n society.

Uploading or distributing photos, scans or any content from this boo k without

prior permission is theft of the authors intellectual property. Please honor the authors work as you would your own. Thank you in advance for respecting our author s rights.

Alicia Malone received permission to publish the included essays by: Jamie Broadnax, Monica Castillo, Jacqueline Coley, Roth Cornet, Aline Dolinh, Grae Drake, Marya Gates, Aisha Harris, Jenna Ipcar, Miri Jedeikin, Sumeyye Korkaya, Tomris Laffly, Moira Macdonald, Jessie Maltin, Merritt Meacham, Amy Nicholson, Carla Renata, Piya Sinha-Roy, Farran Smith Nehme, Danielle Solzman, Tiffany Vazquez, Holly Weaver, Clarke Wolfe, April Wolfe, Alana Wulff, and J en Yamato.

For permission requests, please contact the pub lisher at:

Mango Publis hing Group

2850 Douglas Road, 3rd Floor

Coral Gables, FL 33134 USA

inf o@mango.bz

For special orders, quantity sales, course adoptions and corporate sales, please email the publisher at sales@mango.bz. For trade and wholesale sales, please contact Ingram Publisher Services at customer.service@ingramcontent.com or +1.800 .509.4887.

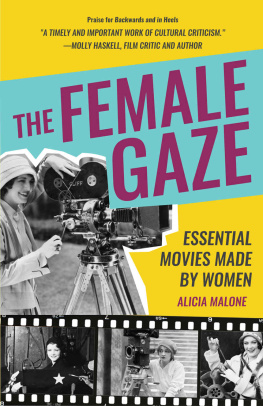

The Female Gaze: Essential Movies Mad e by Women

Library of Congress Cataloging

ISBN: (print) 978-1-63353-837-5 (ebook) 978-1-6 3353-838-2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018959944

BISAC category code: BIO022000 BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAP HY / Women

ART057000 ART / Film & Video SOC010000 SOCIAL SCIENCE / Feminism & Femin ist Theory

Printed in the United States of America

Dedicated to all the film lovers, supporters of women in film,

and aspiring filmmakers out there

Contents

Introduction

One might simplify this by saying: men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an objectand most particularly an object of vision: a sight.

John Berger, Ways of Seeing

In 1973, film critic Laura Mulvey wrote an explosive essay called Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. In it, she used examples from Hollywood films to explore how the perspective of the camera lens (the types of angles, editing, and lighting used) is masculine, with the women onscreen looked at as passive sexual objects. There are many examples of this throughout film history, from the way Lana Turners character is introduced legs first in The Postman Always Rings Twice to Megan Fox leaning over a car engine in Transformers . These two movies are very different, but in both cases the camera directly mirrors the hungry gaze of the male c haracters.

Mulveys piece quickly became famousand contentiousand her ideas continue to be dissected today. To put it simply, Mulvey was interested in what happens to us when the majority of the films we watch are made by men and seen through this male gaze. This gaze places the male characters in a position of power. In film, men are almost always doing the looking , with women left in the weaker position of being looked at . This not only contributes to the slew of passive female characters we see onscreen, but also affects how each of us view womenand how women view th emselves.

There is a very good argument to be made that an equivalent female gaze simply cannot exist, because society is not set up that way. The male gaze is a byproduct of our imbalanced world, one where men hold the majority of the power. While the term the female gaze is used throughout this book (and as its title), this is not intended to imply a narrow view of gender or an ignorance of the structure of our world. It is a phrase used here to open up a conversation about the experience of seeing film and being seen in film for those who dont identify with being white, cis , or male.

What happens, for example, when we look at the world from a female point of view? How do women see themselves? How do women see other women? What makes a movie essentially feminine? What can audiences of any gender identification gain by looking at film through a female lens? These and other questions are at the heart of t his book.

With conversations about womens experiences in Hollywood currently at fever pitch, I am often asked how to best support women in film. The answer? Watch movies made by women. Every click, download, or DVD purchase helps to send a message that we want more. That is why I wanted to write the book you now hold in your hands: to provide an easy, accessible list of some of my favorite movies made by womenmany of whom have been overlooked or forgotten, despite their important contributions to the history o f cinema.

Each of the fifty-two films in this book is made by a woman and features stories about women. Though the focus is mainly on narrative and drama in films, each of the movies you will discover here is unique in tone and genre, and they are drawn from across very different time periods and locations. Some of my criteria in choosing the films was intended to ensure that there was a representation of diversity of era, country, race, and sexual orientation; and that each film is readily available to watch on streaming servic es or DVD.

As a way to include voices other than my own, I asked a group of established and aspiring female film critics to write short odes to movies they love made by women. This book represents a wealth of perspectivesand while at times their choices mirrored my own, at other times they helped to introduce even more films to this packed little guidebook. From dreamlike portrayals of turn-of-the-century matriarchal families to unapologetic explorations of sex work and complex female friendships, there is something here for everyone.

For each film chosen here, you will find the production details, a short synopsis, and some interesting backstory about the film and its filmmaker, along with what the uniquely feminine perspective does for the story. The idea is to give you the flavor of what each film offers and why I feel it is worth redi scovering.

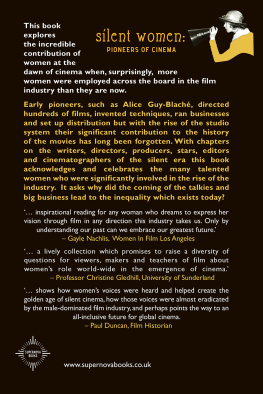

As you move through these chapters, there are several things to note; first, the sparseness of female-directed films at the beginning of the twentieth century and how that changed starting in the 1970s. Youll also note how its not until the 1990s that I include a female director of color, and how many of these filmmakers only made one feature film. There are also quite a few directors who eschew the modifier of female or who have rejected the notion of their films being called feminist. And the quotes used from critics and authors mainly come from white men. All of this demonstrates how female filmmakers (and our experiences of film as a whole, including who has historically written about film) have been limited by the barriers of gender, race, and sexual or ientation.

It can be frustrating to wonder what kinds of stories we might have experienced if a wider variety of people had been allowed to tell them. But its important to celebrate what we do have, because despite the odds, women have been making movies from the beginning of cinema itself. And there is much more to discover than what I have included. My selection here represents only a small sample of the many wonderful movies that have been directed by female filmmakers. I capped the list at fifty-two in case you wanted to watch a film a week for a year and use this book as part of the #52FilmsByWomen challenge started by the Women in Film organization. But of course, you can simply dip in and out of this collection at your own pace and use this guide to explore those titles that most take yo ur fancy.

Next page