Pagebreaks of the print version

THE VIKING AGE

THE VIKING AGE

A TIME OF MANY FACES

by

CAROLINE AHLSTRM ARCINI

With

T. Douglas Price, Bengt Jacobsson, Maria Cinthio, Leena Drenzel, Bibiana Agust Farjas and Jonny Karlsson

Illustrated by

Staffan Hyll

Published in the United Kingdom in 2018 by

OXBOW BOOKS

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford, OX4 1JE

and in the United States by

OXBOW BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083

Oxbow Books and Caroline Ahlstrm Arcini 2018

Paperback Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-938-8

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-939-5 (epub)

Kindle Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-940-1 (mobi)

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018939501

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

For a complete list of Oxbow titles, please contact:

UNITED KINGDOM

Oxbow Books

Telephone (01865) 241249

Email:

www.oxbowbooks.com

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Oxbow Books

Telephone (800) 791-9354, Fax (610) 853-9146

Email:

www.casemateacademic.com/oxbow

Oxbow Books is part of the Casemate Group

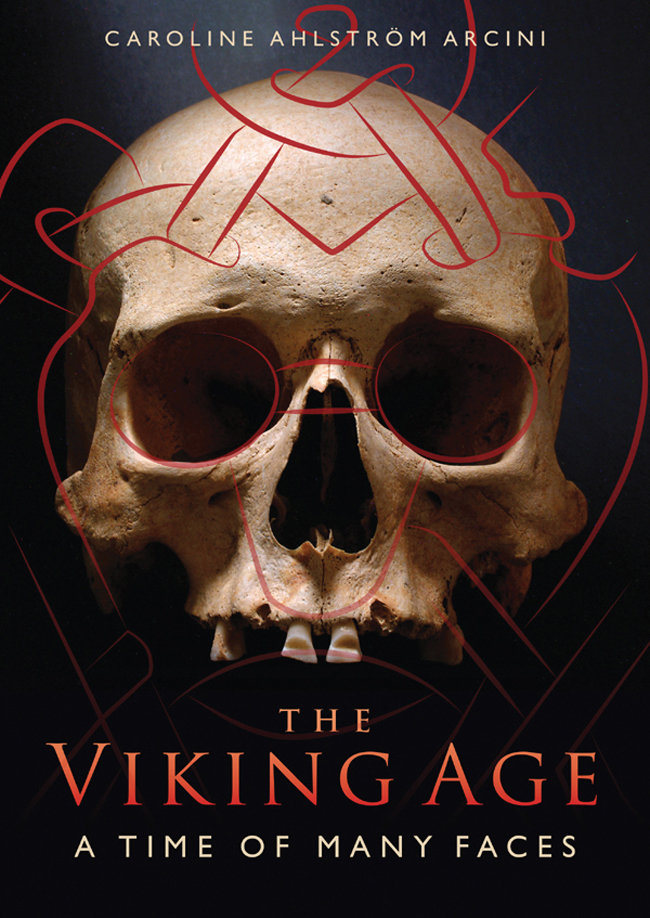

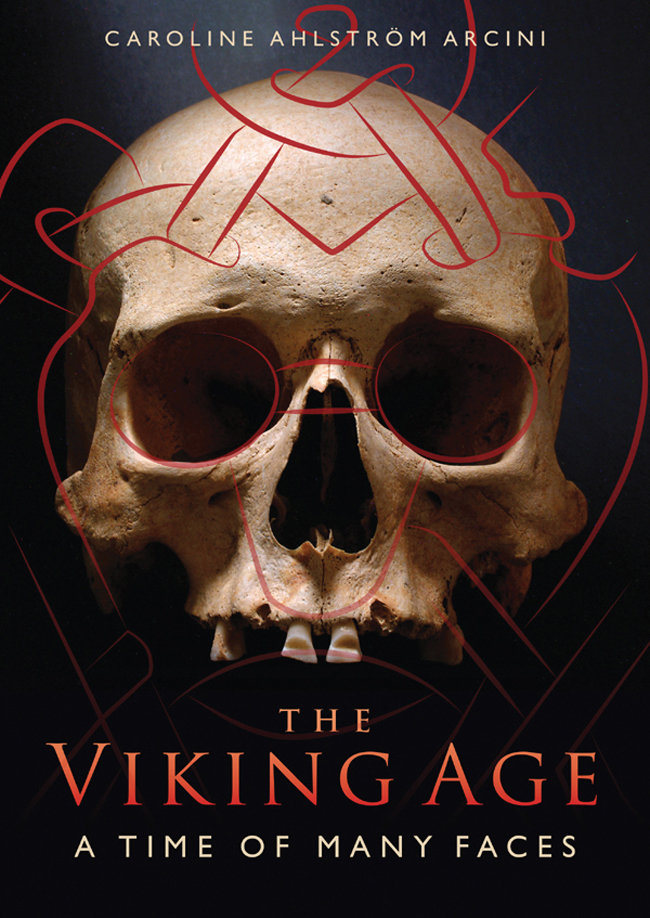

Front cover: A male skull with filed teeth from the Viking Age cemetery in Fjlkinge, north-east Skne in Sweden. Superimposed on the skull is a mask from a runestone in Lund, Lundagrsstenen DR 314. (Photo Staffan Hyll)

Preface and acknowledgment

Suffice it to say, the Viking Age represents the most exposed period in the prehistory of Scandinavia, with many academic texts as well as representations in popular culture. Too often, however, the descriptions about this period concentrate on death, violence, raids and fear. However, archaeological and osteological studies have delivered, and continue to deliver, other perspectives regarding Viking Age society. This book is one such example, where the everyday life of people is in focus. It is via the skeletons that we present the life history of children and adults during the Viking Age. As an osteologist working in the field of archaeology I regularly work with human skeletal remains from the Viking Age. The material presented here is based on excavations from the twentieth century. The purpose of the project was to synthesize what the skeletons tell us about the living condition for people during the Viking Age.

Several colleagues have in various ways contributed to this publication. My husband Torbjrn Ahlstrm, Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Lund University, suggested already at the beginning of this project that we should use strontium isotopes to map mobility in Viking society. Douglas Price, University of Wisconsin, with his knowledge and experience of this method, has contributed not only to this publication, but also through other studies showing the variation in mobility in Scandinavia during this period. Leena Drenzel, National Historical Museum, Stockholm, has spent several weeks with me in the museum depot in Tumba, where teeth were studied under the magnifying glass. Jonny Karlsson, National Historical Museum, Stockholm, Bibiana Agust Farjas, Insitu S.C.P. Arqueologia funerria, preventiva i patrimoni cultural Begur/Centelles/Sant Feliu de Guxols, and Torstein Sjvold have delivered discoveries of new cases of modified teeth in Sweden. I also thank Johan Calmer and Ingmar Jansson for communicating contacts in Russia and Ukraine in search of possible traces of the phenomenon of modified teeth. Bengt Jacobsson, Riksantikvariembetet UV Syd, and Bertil Helgesson, Sydsvensk Arkeologi AB, first introduced me to grave materials from the Viking era. Together with Maria Cinthio, I have had intensive and constructive discussions about Viking burials in a Christian context and especially in Lund. Dan Carlsson, Arendus and Lena Thunmark-Nyhln have been valuable discussion partners regarding the Gotlandic surveys. Together with Per Frlund, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, I have worked with the graves from Skmsta. Rita Larje has provided valuable osteological information about the graves from the cemetery in Kopparsvik, Gotland. With Mattias Toplak, Eberhard Karls Universitt, Tbingen, I have had several interesting discussions regarding the phenomenon of prone burials. Gunnar Andersson, National Historical Museum, and Ingrid Gustin, Department of Archaeology, Lund University, have contributed information regarding Birka. I have had interesting discussions regarding strontium with Ola Magnell and Mathilda Kjllquist, The Archaeologists, National Historical Museum, and Helene Wilhelmson, Sydsvensk Arkeologi AB. I have discussed the difference between Slavic ceramics and Baltic ware with Mats Roslund, Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Lund University, and Torbjrn Brorsson, KKS. I want to thank Gran Possnert, Tandem Laboratory at Uppsala University for radiocarbon dates. I have received valuable comments on the text, especially from my good friend Annica Cardell. The translation into English was made by Alan Crozier. I also want to thank Helene Borna-Ahlkvist at The Archaeologists, National Historical Museum, for support during the whole project. Funding has been provided from the Birgit and Gad Rausing Foundation for Humanistic Research, Ebbe Kock Foundation, Berit Wallenberg Foundation, Gotlandsfonden, ke Wibergs stiftelse and DBV. I also want to thank Gotlands fornsal in Visby, National Historical Museum, Stockholm, Historical Museum and Kulturens Museums in Lund and Trelleborg Museum in Trelleborg. Finally I will thank Staffan Hyll who has a fantastic ability to visualize my ideas as comprehensible illustrations.

I dedicate this book in memory of my tutor, colleague and good friend Pia Bennike, who followed and supported this project from the beginning but alas, did not see the final book.

1

The bare bones

Vikings . Say the word and we think of robbery, rape and pillage, assault, battles, kings, chiefs, mercenaries, and colonization. Vikings . We think of ships, long-distance travel and connections, runes, buried hoards of silver, and trade in both goods and people. Vikings . We think of the meeting between paganism and Christianity. Vikings . We think of the Icelandic sagas, of European settlers in Greenland and Vinland and ibn Fadlans descriptions of the Norse traders in the east, Rus as tall as palm trees, with blond hair and tattooed bodies and young female slaves following their masters into death. But there is much more to tell.

Some scholars believe that the Viking Age is not a correct designation because the word Viking mainly denotes a pirate and describes only that part of the population who set off on plundering expeditions.

Although the word Viking is mainly associated with the more violent activities of this period, precious metals in different shapes and labour in the form of slaves were brought home and thus also benefited the more sedentary part of the Norse population. In other words, the results of the actions performed by the Vikings were deeply integrated in the society of the time. The traces of the period we today call the Viking Age, AD c . 7501050, represent both those who travelled on raids and military expeditions, and those who peacefully pursued trade and made their living from what the farm yielded. Representatives of the different groups were, in all probability, intimately associated with one other. So, is it really possible to distinguish between those who are called Vikings and the rest of the population?