Table of Contents

Imperial Oil Company Financial Statements, 189298

Imperial Oil Production, Sales, and Net Earnings, 191220

Imperial Oil Ltd., Income Received and Dividends Paid,

192147

Imperial Oil Sales, Production, Earnings, and Dividends,

194780

Canadian Oil Companies, Comparison, 1947

Canadian Oil Companies, Comparison, 1994

PART TWO

before leduc 19171947

4

Adventures in the Tropics

The Genesis of International Petroleum

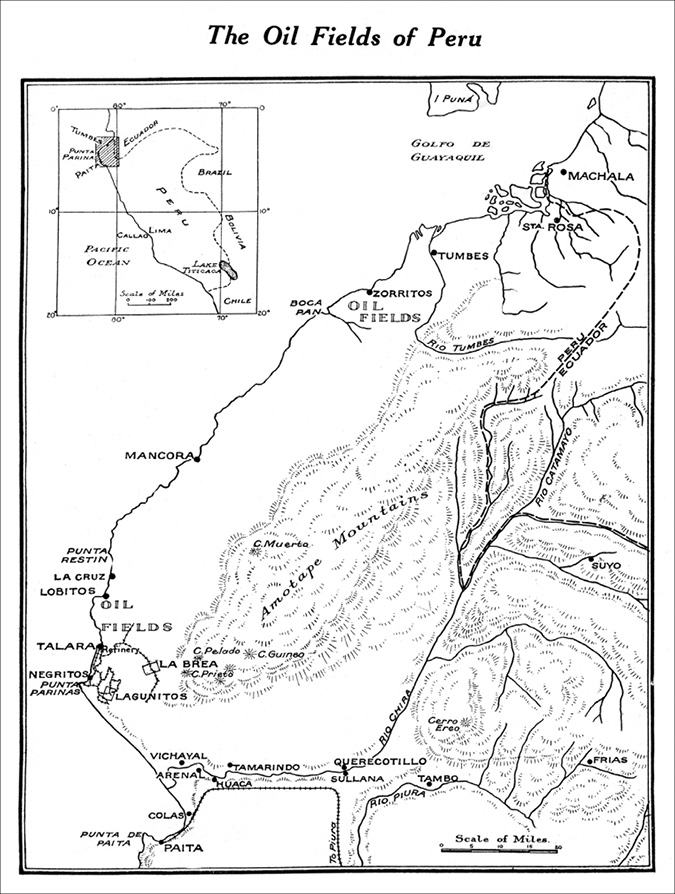

Early in 1913, Sir Archibald Williamson and Kenneth Mathieson representatives of the heirs of the late William Keswick of Londoncontacted Walter C. Teagle, the vice president and member of the board of directors of Standard Oil of New Jersey, with a proposal to sell the shares owned by Mr. Keswick in the London & Pacific Petroleum Company to Standard. London & Pacific had been established in 1889 by partners in the merchant houses of Jardine Mathieson and Balfour, Williamson, to develop oil fields on the La Brea y Parinas Estate on the northern coast of Peru, based on a ninety-nine-year lease of the mineral rights of the estate. Keswick had been the major investor in the company, and the shares offered would effectively transfer ownership of London & Pacific to the American company.

Over the next few months negotiations ensued and Jersey Standard dispatched a mission headed by John H. Carteralso a Standard director and a veteran of the oil business going back to the development of the Pennsylvania fields in the mid-nineteenth centuryto survey the potential costs and benefits of taking over the Peruvian venture, which up to that point had exhibited limited success, producing at most 400 bbl./day by 1913although that still made Peru the second-largest contemporaneous oil exporter in Latin America, following Mexico. Carters report was positive, indicating that with the kind of technical and management capabilities that Jersey Standard could provide, production from the proven reserves could be substantially expanded. Teagle advocated a more ambitious plan, which involved acquiring not only the La Brea estate but also the assets of all the other companies operating in the area under sub-leases from London & Pacific.

The parties reached an agreement that took effect on November 2, 1914. The company that acquired these assets, however, was not Jersey Standard but a new entity, the International Petroleum Company Ltd., which was to be a subsidiary of Imperial Oil Ltd. A major issue for both Imperial Oil and Jersey Standard was access to oil reserves. Imperials output from the Petrolia fields had declined to the point that by 1912 its Sarnia refinery was increasingly dependent on supplies from Cygnet, Ohio. Jersey Standard had a huge refining capacity after the breakup of the Standard Oil Trust, but few new producing fields, and it needed to find alternative sources to serve the East Asian markets. Wearing both his Imperial and Jersey Standard hats, Teagle set out to find new sources. Consequently, the London & Pacific offer was particularly attractive. But for several other reasons, from Teagles viewpoint orchestrating the acquisition through Canada was useful.

The issue of nationality was a factor, as the British shareholders in London & Pacific preferred to deal with a British company rather than the American behemoth.

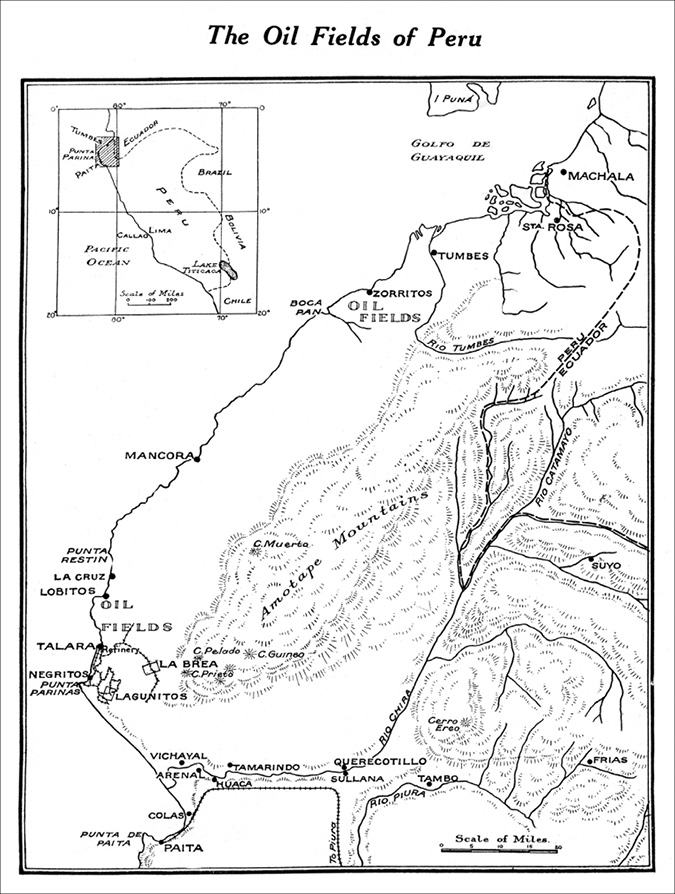

Map 4.1 . Oil Fields in Peru, Imperial Oil Review , June 1922, p. 5. Courtesy of the Glenbow Archive, Imperial Oil Collection.

But Teagles ambitions extended well beyond the acquisition of an oilfield in Peru. In the aftermath of the antitrust suit, and the election of Woodrow Wilson as President (he had been the governor of New Jersey when the states corporate reform act was passed), there was widespread distrust in the halls of 26 Broadway, Jersey Standards headquarters, about the future intentions of US government policies toward big business, in particular the possible extension of the Sherman Act to monopolies in foreign nations. Although International Petroleum did not become the vehicle for all of Jersey Standards foreign ventures, for Teagle it was a handy device when needed.

In December 1914 Imperial Oil approved the establishment of International Petroleum Company as a subsidiary, acquiring all the La Brea estate and most of the associated enterprises. The companys authorized capital was $20 million (CAD), of which $5.2 million in common stock and $500,000 in preferred shares were issued in early 1915. Teagle was the president, and G. Harrison Smith (who would succeed Teagle as president of IPC in 1917 and later became head of Imperial) was vice president. In its public communications the new company emphasized that IPC was to provide crude oil from Peru to Imperials Vancouver refinery for western Canadian markets.

Teagle dispatched petroleum engineers and drillers to develop the La Brea fields, most of them Americans since Imperial had no producing staff at that time.

IPCs relations with the government of Peru, however, were not developing as smoothly as production in the fields. By the second decade of the twentieth century, there was increasing tension throughout much of Latin America over the rapid growth of foreign direct investment in the region, directed both at the foreigners and at the politicians who were perceived as working for them. Admittedly British, French, and German capitalists were very much a part of these developments; nevertheless, a decade of Big Stick diplomacy by the United States had encouraged particular animosity toward American business. And although IPC was a Canadian subsidiary, it was largely perceived in the countries where it operated as an arm of the Standard Oil octopus.

Revolutionary nationalism and anti-American sentiments were most prevalent in Mexico and Colombia, but Peru was also experiencing political turmoil. In 191415, while Jersey Standard and Imperial Oil were setting up IPC, Peru was convulsed by civil strife, a military coup, and eventually the election of a new president, Jos Pardo y Barreda. Although no radical, Pardo found it politic to cater to the nationalist sentiment that focused on the threat of this new foreign behemoth.

The Pardo government brought forward a series of tax measures, beginning with a revision of the original La Brea concession that increased the mining tax to cover all lands in the estate regardless of whether or not they were developedthis was based on the view that London & Pacific had consistently understated the extent of their development in order to avoid taxation. Next, taxes were proposed on production and exports, both specifically to be imposed on IPC. The company responded in a variety of ways: seeking to negotiate a compromise on the concession issue (which proved fruitless), lobbying against the bills, challenging the proposals in court, demanding that the issue be subject to international arbitration (through Britain, and later the Hague), and threatening to curtail production.

The confrontation reached a critical point in 1918 when the IPC announced that the Canadian government had requisitioned its tankers to serve with the convoys in the Atlantic carrying supplies to Britain. This was in response to Germanys vigorous U-boat campaign, and Imperial Oil had already contributed its own tankers to convoy duty. But to the government of Peru, the move appeared to be another pressure tactic by IPC, which closed down operations for several months, leaving Lima stranded with a limited supply of oil. Many Peruvians viewed IPCs moves with skepticism, since from their perspective the real parent of IPC was the American company Standard Oil. Several accounts of this episode indicate that these suspicions were not without substance and that the Canadian government did not specifically requisition two of the IPC tankers.