Contents

Guide

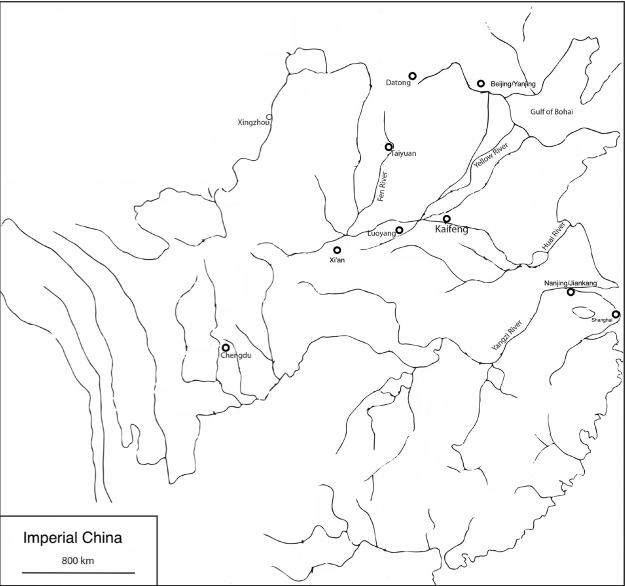

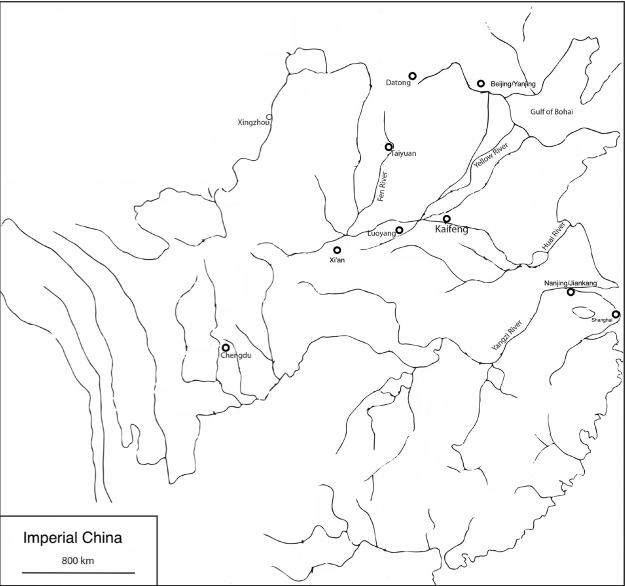

Imperial China

A Beginners Guide

Imperial China

A Beginners Guide

Peter Lorge

A Oneworld Book

First published by Oneworld Publications in 2021

This ebook edition published 2020

Copyright Peter Lorge 2021

The moral right of Peter Lorge to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78607-578-9

eISBN 978-1-78607-579-6

Typeset by Geethik Technologies

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London WC1B 3SR

England

Stay up to date with the latest books, special offers, and exclusive content from Oneworld with our newsletter

Sign up on our website

oneworld-publications.com

This book is dedicated to the memory of my father, Bernd Lorge (19332016), who I hope would have appreciated my efforts to speak to a larger audience

Contents

A Timeline of the Dynasties of Imperial China

Qin | 221206 BCE |

Han | 202 BCE220 CE |

Former/Western Han | 202 BCE23 CE |

Xin (interregnum) | 923 CE |

Later/Eastern Han | 25220 CE |

Wei, Jin, Nan-Bei Chao | 220589 |

Three Kingdoms | 220280 |

Wei | 220265 |

Han (Shu Han) | 221263 |

Wu | 222280 |

Jin | 265420 |

Western Jin | 265316 |

Eastern Jin | 317420 |

Six Dynasties | 222589 |

Sixteen Kingdoms | 304439 |

Northern and Southern Dynasties (Nan-Bei Chao) | 420589 |

Southern Dynasties | 420579 |

Liu Song | 420479 |

Qi | 479502 |

Liang | 502557 |

Chen | 557589 |

Northern Dynasties | 386581 |

Northern Wei | 386534 |

Eastern Wei | 534550 |

Western Wei | 535556 |

Northern Qi | 550577 |

Northern Zhou | 557581 |

Sui | 581618 |

Tang | 618907 |

Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period | 907960 |

Northern Dynasties | 907960 |

Ten Kingdoms | 907979 |

Song | 9601279 |

Liao (Kitan) | 9161125 |

Jin (Jurchen) | 11151234 |

Yuan (Mongol) | 12791368 |

Ming | 13681644 |

Qing (Manchu) | 16441912 |

Introduction

Imperial Chinese history began with the first ruler of China to call himself emperor (huangdi) and ended with the last person to do so. This period, from 221 BCE to February 12, 1912 CE, was immensely diverse, spanned vast cultural change, and saw ruling dynasties lay claim to a varied territory. The same could be said of many other historical constructs, yet the image of China stands apart in human civilization precisely because of its claims to coherence and continuity. This is partly the result of a long and unbroken written tradition, and partly due to the perspective of outsiders, most importantly those in the West who sought a distinctive other against which to define themselves.

Modern Chinese scholars, statesmen, and thinkers have been heavily influenced by outside perspectives on China, and reacted in their own way to this construction of their culture. In large measure, Western perspectives have simply been accepted, if sometimes only as a starting point from which to rebel, and have framed the discussion. This isnt surprising given that the current rulers of China hold to a Western ideology, Communism. Imperial Chinas encounter with Europe and modernity from the late sixteenth century on was not always pleasant, and the ensuing history of misunderstandings, slights, exploitation, and mistreatment on all sides marks how we see the past.

Western Eurasian traders originally went to China, following in the footsteps of previous generations, to exchange goods. But the nature of that interaction shifted in the sixteenth century, when Jesuit missionaries traveled east to convert people to Christianity. Given how few men were actually on the ground proselytizing in China, they were remarkably successful, but it was clear to many of those early missionaries that it would be very difficult to convert the educated elite. Chinese education was closely tied to its own classics and its own ideology. Until well into the nineteenth century Chinese elites were confident of the superiority of their own culture. For most of imperial history, China had been open to outside influences without feeling compromised by foreign cultures. It was only in the middle of the nineteenth century that Chinese attitudes toward Chinese and foreign, really European, culture began to change. That the imperial house of the last dynasty, the Qing (16441912), was Manchu, not Chinese, only served to complicate things further.

Imperial China is therefore very hard to understand when seen only from the perspective of the late Qing dynasty, after Europe had finally surged ahead of the rest of the world technologically. Qing elites, whether Chinese or Manchu, saw themselves as the inheritors of a great civilization. Western technology was interesting and even useful, but Western culture and religion were far less attractive. For their part, Westerners were baffled by the resistance in the nineteenth century to what they believed was an obviously superior culture. Modern technology proved the value of Western culture more generally and, retrospectively, the correctness of its path of historical development. In Western eyes, China was backward in the nineteenth century because it failed to follow the Western course of development. Indeed, China was imagined to have been static over the millennia, fixed in its conservativism. There is a significant danger in writing a history of imperial China that generalizations over two millennia emphasize its cultures ideal or normative image of itself, or at least an outsiders view. In the case of China, this is particularly ironic given that there is more history here than anywhere else.