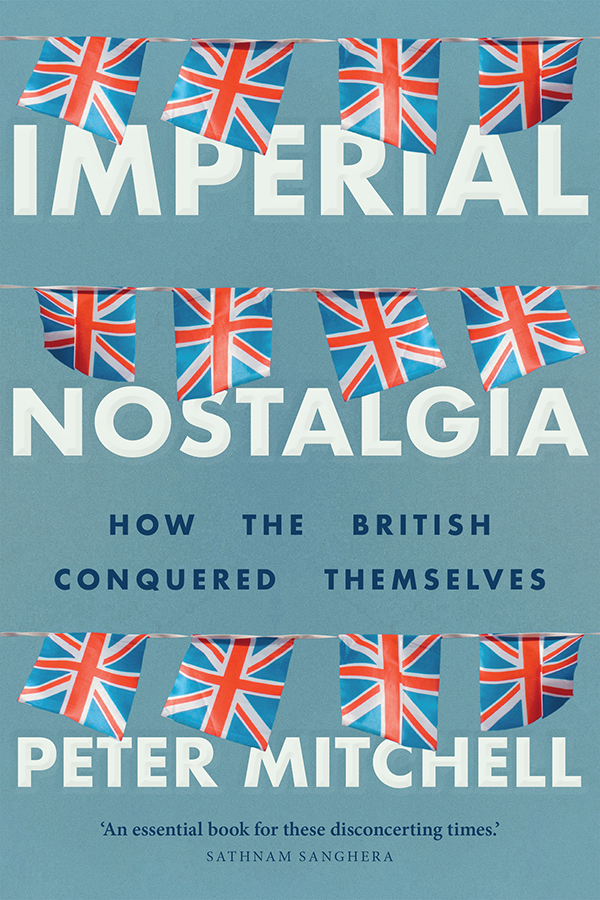

Imperial nostalgia

Imperial

nostalgia

How the British conquered themselves

Peter Mitchell

Manchester University Press

Copyright Peter Mitchell 2021

The right of Peter Mitchell to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 5261 6131 4 hardback

ISBN 978 1 5261 4620 5 paperback

First published 2021

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Cover image: opuscule / Alamy Stock Photo

Typeset By Newgen Publishing UK

For my teachers

Non Omnis Moriar[I shall not wholly die]

Horace, Ode 3.30; written above the

doorway of Cecil Rhodes House, Oxford

Sploosh

Edward Colston (John Cassidy, 1895, bronze casting)

Contents

In 2016, I was employed on an academic project studying the British empire. This project was based around one ambitious idea, which was to try to understand how the British empire worked on a day-to-day basis and on a global scale: as we put it, everywhere and all at once. Approaching the empire as what geographers call an assemblage in this case a vast and intricate structure of steamships, jails, territory, grammar books, memoranda, people, ideology, hydrocarbons, laws, food, files and violence we hoped to come out with some idea of how, across the nineteenth century, the interlinked parts of the global imperial state held together, or didnt. In practical research terms, this meant settling on a few short snapshots of time across the nineteenth century, locating the records of what passed in and out of the agencies of colonial government during those short timescales, and reading every single last one of them.

It was hard work, mostly tedious and occasionally thrilling. Either way, I wasnt very good at it; and, outside the archive doors, certain developments were making it very hard to concentrate. It wasnt just the obvious events of that humid, miserable early summer in which it was always getting hotter but never seemed to get properly light but also the sense behind them of a strange and long-brewing crisis that was assuming everything, piece by piece, into its widening gyre. I knew that this crisis had, somehow, a lot to do with the papers I was ploughing through; that this improbable global tissue of steamships, memoranda, jails etcetera had not only shaped the world I inhabited in a multitude of ways, but was exerting a specific pressure on the present.

One particular morning, only days before the Brexit referendum, I sat down in an unusually good mood. It was Bloomsday, the day on which aficionados of James Joyces Ulyssescelebrate that novels cosmopolitan universalism, its mistrust of the codes of nation, empire and masculinity, and its generous, if merciless, examination of kind, common, troubled, despairing, persistent humanity. I ordered up a volume of papers Id been working through from about the middle of the 1857 Indian uprising, and began to take notes. Then the news began to happen, in hourly increments. The first item of the morning was English football fans taunting migrant children on the streets of Lille; the second the unveiling of Nigel Farages Breaking Point poster, with its photograph of a column of refugees moving inexorably towards the camera. By lunchtime, Jo Cox MP had been murdered by a white supremacist. I looked down at the documents I was supposed to be studying: troop requisitions and tables of payments to P&O for their transport, interdepartmental bickering, breakdowns of the speed of telegraph communication from Suez via Trieste or Marseilles, all the peripheral logistics of a colonial war; and I felt that some violence coded in these documents had somehow found its way back out into the world and begun to wreak havoc again.

Historians since Michelet have written about the moment at which the dead material of the archive comes alive with the shapes of those whose lives are recorded there. This is usually presented as a quasi-miraculous moment: the dead have been made to speak, their voices recovered and their suffering borne witness to. Fewer have written about the sense that, as a scientist might say, their specimens have escaped from the lab. This probably has to do with embarrassment, since historians are supposed to know better than to be surprised. The violence of the past is ongoing in the present; not only structurally, in that it is built into the foundations of the society in which we live, but in more subtle, more constitutive ways: in the words we use, the images we attach to things, the ways we imagine ourselves and each other.