Contents

For Laura and Joe

PROLOGUE

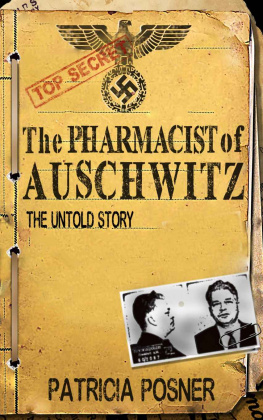

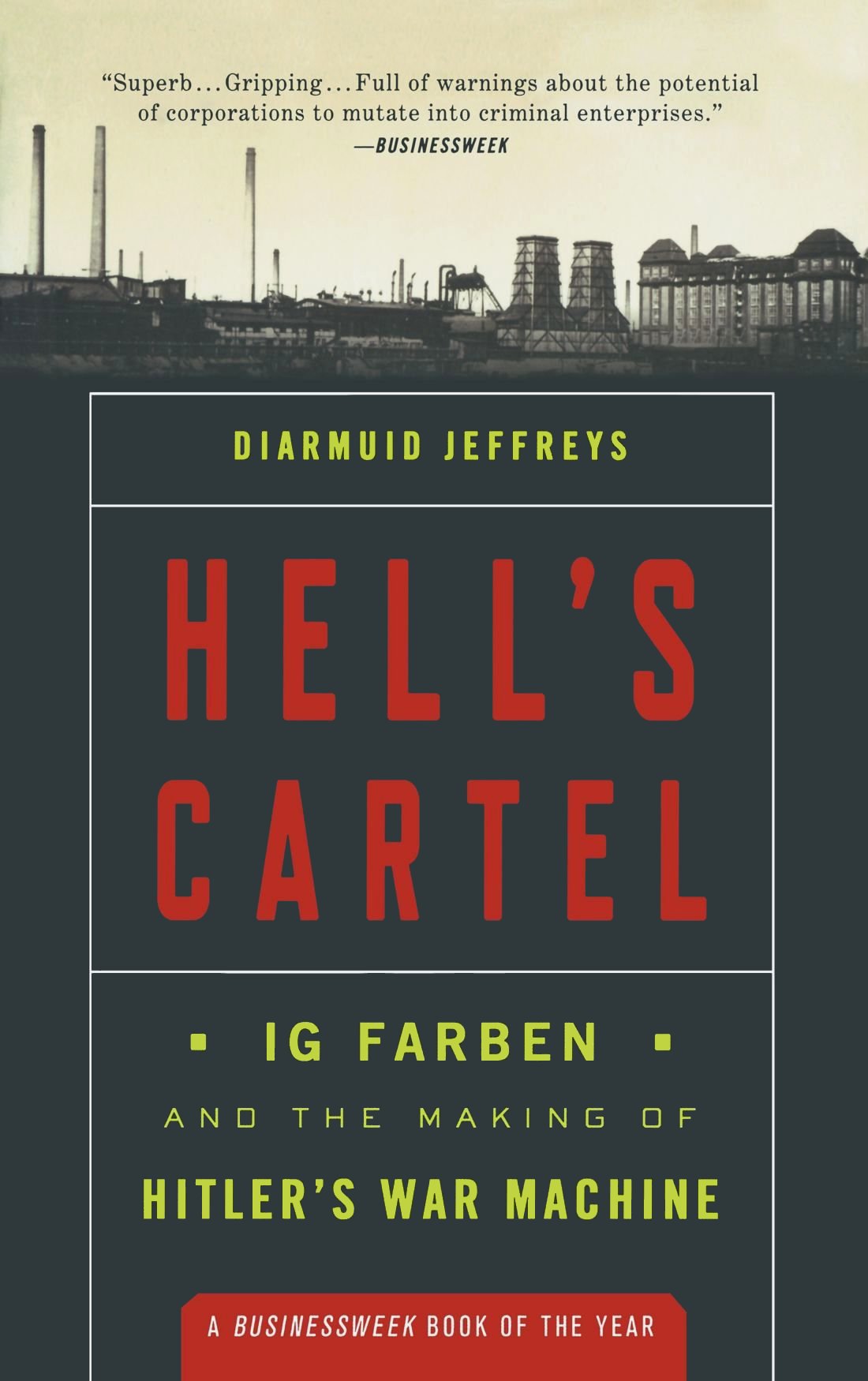

The courtroom was eerily familiar. Most of those in attendance had already seen the chamber in the newsreels or heard it described on the radio or read about it in the newspapers and photographic magazines. This was the place, after all, where only twelve months before, the most famous trial in history had been concluded, where twenty-one leading officials of Adolf Hitlers Third Reich had been called to account for crimes so unprecedented and dreadful that new legal definitions had to be found to describe them. Those men were now all gone, of course; gone to suicide, or to the executioner, or to long prison terms, or even, in the case of three of them, to acquittal and freedombut their names continued to echo through the building and probably always would: Gring, Hess, Speer, Sauckel, Dnitz, Ribbentrop, Streicher, Frank, Jodl, Keitel, Rosenberg, Schacht, Kaltenbrunner

Now another tribunal was getting under way at the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, a new drama that, like its more famous precursor, promised to address many important questions and consequently, on this first day at least, was attracting almost as much attention. The court was packed. Three hundred spectators had been squeezed into the public gallery and demand for places in the press section was so fierce that reporters had to draw lots for a seat or else retire to an adjoining corridor to listen to the proceedings over a loudspeaker.

Those who remained gazed down on the full cast assembled in the wood-paneled chamber below. For much of the morning the many supporting players had been the most active: the functionaries, clerks, translators, technicians, and military police of the war crimes trial administrative staff who would be responsible for the smooth running of things in the weeks and months to come. Although it wasnt strictly necessary for them all to be in court at the same time, it had become something of a tradition to turn up at key moments in important cases and they had all found excuses to be here, bustling about with the papers and equipment that helped to justify their presence.

At the head of the room, four solemn-faced gray-haired judges sat behind a long elevated wooden desk. One was polishing his glasses on his black robe; another jotted notes on a block of yellow paper. The other two were whispering to each other, perhaps discussing the curious history of their bench. Two years earlier, for a few riotous weeks, GIs from the U.S. Armys First Infantry Division had used it as a bar. Up above, in a space once reserved for a glowering portrait of the Fhrer, they had hung a picture of the movie star Lana Turner in a provocatively tight sweater. Now the only decoration was a large Stars and Stripes on a stand behind the presidents chair.

In the central well of the court, the sixty lawyers of the defense team and the dozen or so men and women from the prosecution side sat around tables strewn with documents and law books. Professionally at home in this environment and not easily given to betraying nervousness or anticipation, they were making a languorous show of adjusting their headphones and squaring off their papers.

The twenty-three defendants sat behind them in a two-tiered dock raised to the eye level of the judges. A couple were writing notes, but most were looking around in bemused indignation as though they couldnt quite believe where they were. Earlier that morning they had been taken out of their cells and marched along the covered walkway that connected the jail with the court building. The subsequent two hours had passed in something of a blur. First they had been told to stand as the judges were announced and they came face-to-face with the men who would decide their fate. Then a spokesman for their counsel had tried, with great bluster but no obvious expectation of success, to get the trial postponed on the grounds that the defense had not been given sufficient time and resources to adequately prepare. When the motion was denied, a court official had passed among them with a microphone on a long pole and they were asked to answer the charges. Had they been served with a copy of the indictment in German and had they read it? If so, how did they plead? Each of them had replied Not guilty but only one or two had made this statement with any real show of defiance. Everyone else just wanted the real proceedings to begin.

A low, expectant murmur rippled through the public gallery as a crisply uniformed figure got to his feet at the prosecution table and walked across to a lectern in the center of the court. A clerk glanced up at a clock on the wall and made a note of the time. It was shortly before noon on August 27, 1947.

May it please the tribunal.

As he waited for silence to fall, General Telford Taylor looked across at the men in the dock. They were all older than him, most well into middle age and conservatively dressed in suits and ties. Although they had been in custody for some months and a few had an obvious prison pallor, to his eye they still seemed to exude an air of affronted authority. In another setting they might have been taken for a group of civic dignitaries brought together for a commemorative photograph and tediously detained for a few minutes longer than was necessary. Taylor knew that what he was about to say, and how he said it, could change their lives for better or for worse. He dearly hoped it would be for worse. It had taken a considerable effort to get these men into court: exhausting months of planning and preparation, of frustrating searches for evidence and witnesses, of sifting through thousands of pages of arcane technical documents in an alien language and reading hundreds of statements about shocking crimes. The process had taken a toll on his patience and left him with little sympathy for the lords of IG Farben.

He looked back at the judges and continued.

The grave charges in this case have not been laid before the Tribunal casually or unreflectingly. The indictment accuses these men of major responsibility for visiting upon mankind the most searing and catastrophic war in modern history. It accuses them of wholesale enslavement, plunder and murder. These are terrible charges; no man should underwrite them frivolously or vengefully or without deep and humble awareness of the responsibility, which he thereby shoulders. There is no laughter in this case, neither is there any hate.

The world around us bears not the slightest resemblance to the Elysian Fields. The face of this continent is hideously scarred and its voice is a bitter snarl; everywhere mans work lies in ruins and the standard of human existence is purgatorial. The first half of this century has been a black era; most of its years have been years of war or of open menace or of painful aftermath and he who seeks today to witness oppression, violence or warfare need not choose his direction too carefully nor travel very far. Shall it be said, then, that all of us, including these defendants, are but children of a poisoned span? And does the guilt for the wrack and torment of these times defy apportionment?

It is all too easy thus to settle back with a philosophic shrug or a weary sigh. Resignation and detachment may be inviting, but they are a fatal abdication. God gave us this earth to be cultivated as a garden, not to be turned into a stinking pit of rubble and refuse. If the times be out of joint, that is not accepted as a divine scourge, or the working of an inscrutable fate which men are powerless to affect. At the root of these troubles are human failings and they are only to be overcome by purifying the soul and exerting the mind and body.