CONTENTS

Richard G. Newhauser

Chris Woolgar

Kathryn Reyerson

Martha Carlin

Batrice Caseau

Pekka Krkkinen

Faith Wallis

Vincent Gillespie

Eric Palazzo

Hildegard Elisabeth Keller

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologizes for any errors or omissions there may be in the credits for the illustrations and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future editions of this book.

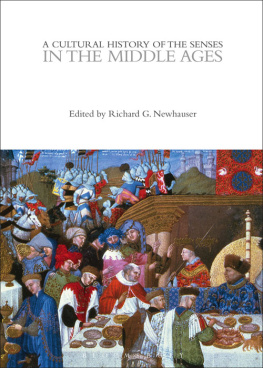

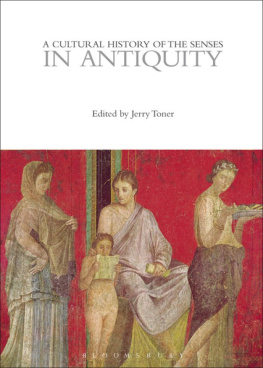

GENERAL EDITOR, CONSTANCE CLASSEN

A Cultural History of the Senses is an authoritative six-volume series investigating sensory values and experiences throughout Western history and presenting a vital new way of understanding the past. Each volume follows the same basic structure and begins with an overview of the cultural life of the senses in the period under consideration. Experts examine important aspects of sensory culture under nine major headings: social life, urban sensations, the marketplace, religion, philosophy and science, medicine, literature, art, and media. A single volume can be read to obtain a thorough knowledge of the life of the senses in a given period, or one of the nine themes can be followed through history by reading the relevant chapters of all six volumes, providing a thematic understanding of changes and developments over the long term. The six volumes divide the history of the senses as follows:

Volume 1. A Cultural History of the Senses in Antiquity (500 BCE 500 CE )

Volume 2. A Cultural History of the Senses in the Middle Ages (5001450)

Volume 3. A Cultural History of the Senses in the Renaissance (14501650)

Volume 4. A Cultural History of the Senses in the Age of Enlightenment (16501800)

Volume 5. A Cultural History of the Senses in the Age of Empire (18001920)

Volume 6. A Cultural History of the Senses in the Modern Age (19202000)

First and foremost, I wish to acknowledge the inspiration in studying the senses that the work of Constance Classen and David Howes has provided, not just to me, but to an entire generation of students of the senses. Without their demonstration of the possibilities and opportunities of sensology, this volume would never have taken the shape it has now.

I am also grateful to Bloomsbury for financial support in reproducing some of the images found here. The chapters by Chris Woolgar, Kay Reyerson, and Batrice Caseau contain photographs they took themselves; I am grateful to them for allowing these images to be reproduced in this volume. Images in the public domain were made available by The British Library, London, and Wikimedia. I also wish to express my gratitude to a number of institutions or individuals for permission to reproduce material under copyright in their collections. This material is found in chapters by the authors whose names are given in parentheses in the following list: the Warden and Fellows of All Souls College, Oxford (Wallis); the Bibliothque de lEcole des Beaux- Arts, Paris (Palazzo); the Bibliothque Nationale de France, Paris (Palazzo); The British Library, London (Wallis); Getty Images (Woolgar); the Herzog-August-Bibliothek, Wolfenbttel (Keller); the Lilly Library at Indiana University, Bloomington (Keller); the sterreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna (Wallis); the Stadt- und Universittsbibliothek Frankfurt and the Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung, Frankfurt a.M. (Palazzo); the Jan Thorbecke Verlag, Sigmaringen (Keller); the Universittsbibliothek Erlangen-Nrnberg (Newhauser); the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (Woolgar); and Stuart Whatling, who maintains the website The Corpus of Medieval Narrative Art (Carlin).

Finally I wish to thank Ms. Sunyoung Lee, a graduate student in Medieval Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe, for her assistance in assembling the index.

Introduction: The Sensual

Middle Ages

RICHARD G. NEWHAUSER

Recent scholarship on the senses has demonstrated that an essential step in writing a comprehensive cultural history involves the reconstruction of a periods sensorium, or the sensory model of conscious and unconscious associations that functions in society to create meaning in individuals complex web of continual and interconnected sensory perceptions (Classen 1997: 402; Corbin [1991] 2005; Howes 2008). This reconstructive task of sensology is required for any period. But it has a claim to be particularly indispensable for understanding the Middle Ages because both a theoretical and a practical involvement with the senses played a persistently central role in the development of ideology and cultural practice in this period (Howes 2012; Newhauser 2009). Whether in Christian theology, where the senses could be a fraught and debated presence; or in ethics, which formed a consistent and characteristic element in understanding the senses in the Middle Ages; or in medieval art, where sensory perception was often understood to open the doors to the divine; or in the daily activity of laborers, from agricultural workers to physicians, sailors to craftsmen, in areas in which machines had not yet replaced the sensory evaluation of work by human beingsin all of these areas, and in many more, the senses were a foundational element in evaluating information and understanding the world. For a number of reasons having to do partially with the alterity of sensory information transmitted by medieval texts and partially with the denigration of sensory perception in many theological works in the Middle Ages, medieval scholars have joined in the undertaking of sensology only in the relatively recent past. It can, in fact, be asserted that this sensory turn is one of the most important ongoing projects of medieval studies in the twenty-first century. And as a recent survey has demonstrated (Palazzo 2012), the past decade of intensive research has already borne significant fruit in understanding the cultural valences of sensory perception in the Middle Ages in their historical development.

THEOLOGY AND THE PORTALS OF THE SOUL

The fall of Rome and the dissolution of imperial regimes of the senses resulted in a certain atomization of paradigms of sensory experience in the context of early medieval courts, the comitatus, the village, or the monastery. For example, in antiquity the indulgence in sensual pleasures by some among the Roman elites, though perhaps not evidence of their identification with the poor, was criticized by authors who considered themselves to uphold traditional standards as a dangerous betrayal of the moral principles that separated the upper levels of society from all that was not ideally Roman (women, foreigners, the lower levels of society) (Toner 1995). But located in decentralized monastic environments, sensual indulgence took on the contours of rebelliousness against Christian faith itself, and it could be condemned as both disobedience and a failure in monastic duty. Typical for early medieval monastic theology dealing with faith, social regulation, and much else, authority for these views was derived through exegesis and homily from the Bible. Augustine of Hippo (354430) and Gregory the Great (d. 604), essential figures both in the monastic tradition and for the secular church, were influential in transmitting the conception of the theological danger of indulging the senses (Newhauser [1988] 2007).

Next page