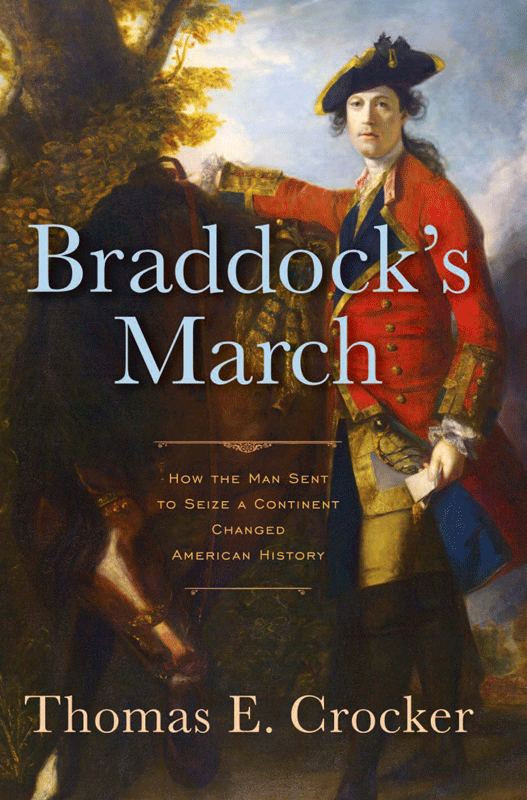

Braddocks March

HOW THE MAN SENT TO SEIZE A CONTINENT CHANGED AMERICAN HISTORY

Thomas E. Crocker

WESTHOLME

Yardley

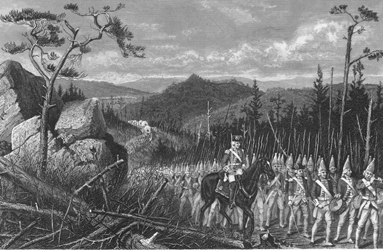

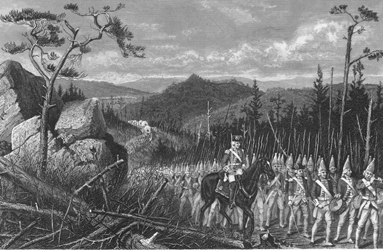

Frontispiece: Braddocks March, an engraving from Washington Irvings The Life of George Washington, 1855.

Copyright 2009 Thomas E. Crocker

Maps 2009 Westholme Publishing, LLC

Maps by Tracy Dungan

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Westholme Publishing, LLC

904 Edgewood Road

Yardley, Pennsylvania 19067

Visit our Web site at www.westholmepublishing.com

ISBN: 978-1-59416-527-6 (electronic)

Also available in hardcover and paperback.

Produced in the United States of America.

For Edward and Thomas

It was long a subject of hot dispute among men whether physical strength or mental ability was the more important requirement for success in war. Before you start on anything, you must plan; when you have made your plans, prompt action is needed. Thus neither is sufficient without the aid of the other.

Sallust, The Conspiracy of Cataline

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

ON SEPTEMBER 24, 1754, William Augustus, the Duke of Cumberland, third son of King George II, and Captain General, or commander-in-chief, of the British army, huddled with his aides at the British armys general staff headquarters at Horse Guards in London. The fine white stone Palladian building had been completed only the year before. With its three-story wings surmounted by a central arch bearing the royal arms of His Majesty, the capacious edifice provided a fitting and modern command post for the organized and reform-minded Cumberland. Built on the site of King Henry VIIIs tilt yard, or jousting ground, the elegant and imposing building served both as the London home of the Foot Guards who protected the King at his residence at nearby St. Jamess Palace and as the nerve center from which Great Britain administered its far-flung military empire. And what more appropriate venue could there be than a royal jousting ground, as Britain squared off one more time against France?

The Duke of Cumberland knew both his own troops and his enemy from first-hand experience. Just nine years before, on May 11, 1745, at Fontenoy in the Low Countries, the duke had ordered the Coldstream Regiment of Foot Guards to wheel into position on the marshy meadows before the River Scheldt. The English troops marched forward as if on parade, while the elite French Guards waited. The English officers led their troops with light rattan canes. As they drew near the French line, they raised their hats in salute to their adversaries. The French politely saluted, declined the English commanders invitation to fire first, and returned the compliment by themselves inviting the English to fire.

And they did. During the course of the battle the Coldstream Foot Guards officers directed the mens muskets with their canes, first to the left and then to the right, a nudge here, a wave of the wand there, as if they were symphonic conductors. The dukes regiment mowed the elite French soldiers down like ripe grain before the sickle.

The battle already had entered the annals of British military history as a model of discipline and efficiency.

Now, nine years later, the joust was about to begin again. The Captain Generals desk was piled high with entreaties for assistance from Governor Dinwiddie in Virginia, with reports about an obscure acting colonel of the colonial militia named George Washington who had single-handedly brought the two great European empires to the brink of war, with intelligence reports about the mineral wealth of the Ohio River valley and the fluid dispositions of the various Indian tribes that inhabited it and with maps procured from the Board of Trade, which was charged with the administration of the North American colonies.

The Duke of Cumberland had done his homework. He had read the reports, and he had studied the maps. He knew the geopolitical grounds, the high stakes, and the urgency as he was about to mount the largest armed expeditionary force ever sent to North America.

On the very maps unrolled on his desk before him it was plain for all to see that the westernmost projection of Anglo-American force, at the combined trading post and fort at Wills Creek in Maryland, was but a mere fifteen miles from Frances Fort Duquesne at the Forks of the Ohio River. It would be short work to paddle up the Potomac River to its junction with Wills Creek and then from there to pounce on the French unexpectedly. Were not the western reaches of British America but little more than fifteen miles wide? The maps, after all, said so.

Of course, there were the Indians to contend with. They were a fickle and confusing lot, one day siding with the English and the next with the French. Hardly worth trying to figure out. Almost one hundred and fifty years of British colonization in America, however, had brought home the one irreducible fact about the Indians: their brutality. They did not fight like the British or the French. They skulked, they scalped, they murdered men, women, and children indiscriminately. Cumberland knew he needed to have a tough and driven commander.

As he looked down at the freshly signed commission on his desk, the Captain General had no question that he had just the person for the job: His Excellency Major General Edward Braddock of the Coldstream Regiment of Foot Guards, Generalissimo of All His Majestys Troops in North America.

LONG OVERSHADOWED BY THE ENSUING DRAMA of the American Revolution, Braddocks march survives today only in traces. Dozens of Braddock sites are taken for granted, faded into the everyday landscape like the memory of what caused themBraddock Road, Braddocks Rock, Braddock Heights, Braddocks Run, Braddock Avenue, Braddock Hills, North Braddock, Mount Braddock, Braddocks Field. They punctuate the map of the twenty-first-century East Coast of America from the suburbs and back roads of Tidewater Virginia and suburban Maryland to downtown Washington, D.C., to the outskirts of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Drivers pass by them; shoppers barely register their existence; even residents take them for granted as part of the everyday landscape.

In the 1750s, it was another story. A British general at the command of some two thousand British soldiers and American militiaat the time the largest professional army ever assembled in North Americamounted one of the most ambitious and remarkable marches in history. As in later wars, they arrived with high intentions, cocksure confidence, and such woeful ignorance that they were swallowed up and destroyed by the reality of the country they had come to save. Their aim was to oust the French, win over hostile Indians, and claim a continent. The British troops who made the march were the first that England had ever sent to America in force. Their route of march slashed like a scar across the center of the American colonies. They blazed a road where only wilderness had existed. They hauled dozens of cannon across mountains that are formidable even now. They faced an enemy whom they did not know. And they were all but wiped out in one of the most humiliating defeats British arms was ever to suffer.