Boom and Bust

Why do stock and housing markets sometimes experience amazing booms followed by massive busts and why is this happening more and more frequently? In order to answer these questions, William Quinn and John D. Turner take us on a riveting ride through the history of financial bubbles, visiting, among other places, Paris and London in 1720, Latin America in the 1820s, Melbourne in the 1880s, New York in the 1920s, Tokyo in the 1980s, Silicon Valley in the 1990s and Shanghai in the 2000s. As they do so, they help us understand why bubbles happen, and why some have catastrophic economic, social and political consequences whilst others have actually benefited society. They reveal that bubbles start when investors and speculators react to new technology or political initiatives, showing that our ability to predict future bubbles will ultimately come down to being able to predict these sparks.

William Quinn is a Lecturer in Finance at Queens University Belfast, where he conducts research on market manipulation, stock markets and, above all, bubbles.

John D. Turner is a Professor of Finance and Financial History at Queens University Belfast. He is a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences and an editor of The Economic History Review . His book Banking in Crisis (2014) won the Wadsworth Prize in 2015.

Boom and Bust

A Global History of Financial Bubbles

William Quinn

Queens University Belfast

John D. Turner

University Printing House, Cambridge CB2 8BS, United Kingdom

One Liberty Plaza, 20th Floor, New York, NY 10006, USA

477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia

314321, 3rd Floor, Plot 3, Splendor Forum, Jasola District Centre, New Delhi 110025, India

79 Anson Road, #0604/06, Singapore 079906

Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge.

It furthers the Universitys mission by disseminating knowledge in the pursuit of education, learning, and research at the highest international levels of excellence.

www.cambridge.org

Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9781108421256

DOI: 10.1017/9781108367677

Cambridge University Press 2020

This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press.

First published 2020

Printed in the United Kingdom by TJ International Ltd, Padstow Cornwall

A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Quinn, William, 1990 author. | Turner, John D., 1971 author.

Title: Boom and bust : a global history of financial bubbles / William Quinn, Queens University Belfast, John D. Turner, Queens University Belfast.

Description: New York : Cambridge University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019048274 (print) | LCCN 2019048275 (ebook) | ISBN 9781108421256 (hardback) | ISBN 9781108367677 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Business cycles History. | Financial crises History. | Business forecasting.

Classification: LCC HB3716 .Q56 2020 (print) | LCC HB3716 (ebook) | DDC 338.5/4209dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019048274

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019048275

ISBN 978-1-108-42125-6 Hardback

Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Contents

Figures

Tables

Chapter 1 The Bubble Triangle

The definition of a bubble we take to be an undertaking which is blown up into an appearance of splendour and solidity, without any probability of permanence, and the name, we take it, is derived from the specious products of puffing and soapy water, with which the most of the ingenious youth of this realm have been long familiar.

Anon.

We have to turn the page on the bubble-and-bust mentality that created this mess.

President Barack Obama

What is the difference between the great composer George Frideric Handel and Shane Filan, the lead singer of Irish boyband Westlife? To those of a musical bent, the answer is obvious: Handel is one of the most respected classical musicians of all time, having composed several famous operas. Filan, on the other hand, largely specialised in saccharine cover versions of 1970s pop songs. The difference that interests us, however, is that while one lost all of their wealth in a bubble, the other got out before a bubble burst, making a handsome profit as a result.

By the time he was 30 years old, Handels musical compositions had already made him a very wealthy man, and his patron, Queen Anne, provided him with a considerable annual income. In 1715 he invested some of his wealth in five shares of the South Sea Companyone of the most successful pop groups of all time and the net worth of the groups four members was over 32 million. Along with his brother, Filan decided to become a property developer in the midst of the Irish housing bubble. In order to purchase as much housing as possible, he supplemented his own funds by borrowing large sums of money from banks. In 2012 he was declared bankrupt, owing his creditors 18 million.

In other words, bubbles waste resources, as clearly illustrated by the half-built houses and ghost housing estates that stood across Ireland when the housing bubble burst. Other inefficiencies are in the realm of labour markets, as people train or retrain for a bubble industry. When the bubble bursts, they become unemployed and part of their investment in education has been wasted. After the collapse of the housing bubble, many of our friends, neighbours and students who had trained as architects, property developers, builders, plumbers and lawyers were either unemployed, in a new industry, or travelling overseas to find work.

The bubble metaphor stuck, but over time its use has become somewhat less pejorative.

Nowadays the word bubble is used by commentators and news media to describe any instance in which the price of an asset appears to be slightly too high. Among academic economists, however, using the word at all can be deeply controversial. One school of thought sees a bubble as a non-explanation of a financial phenomenon, a label applied only to

In this book, we borrow the definition of Charles Kindleberger

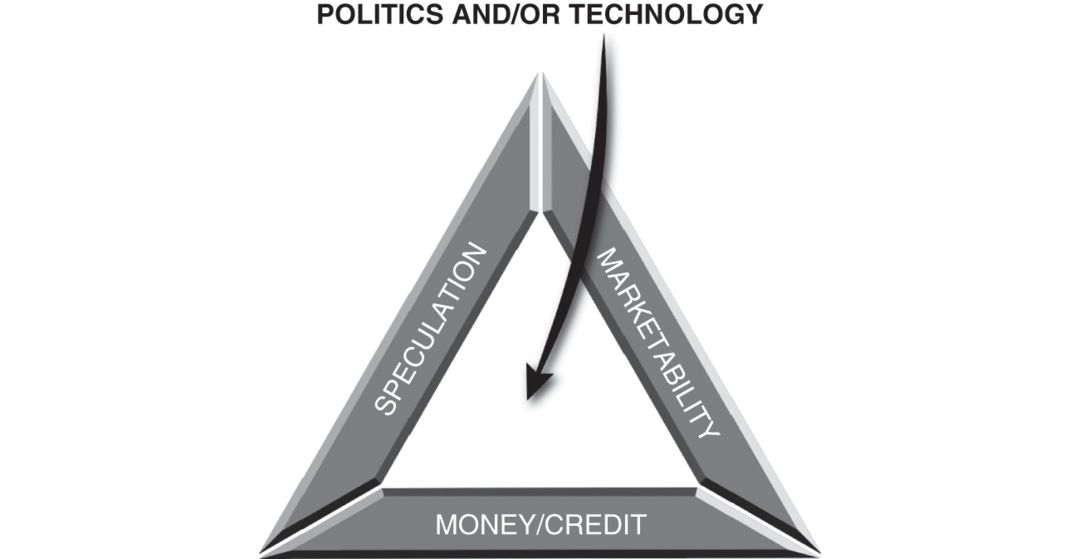

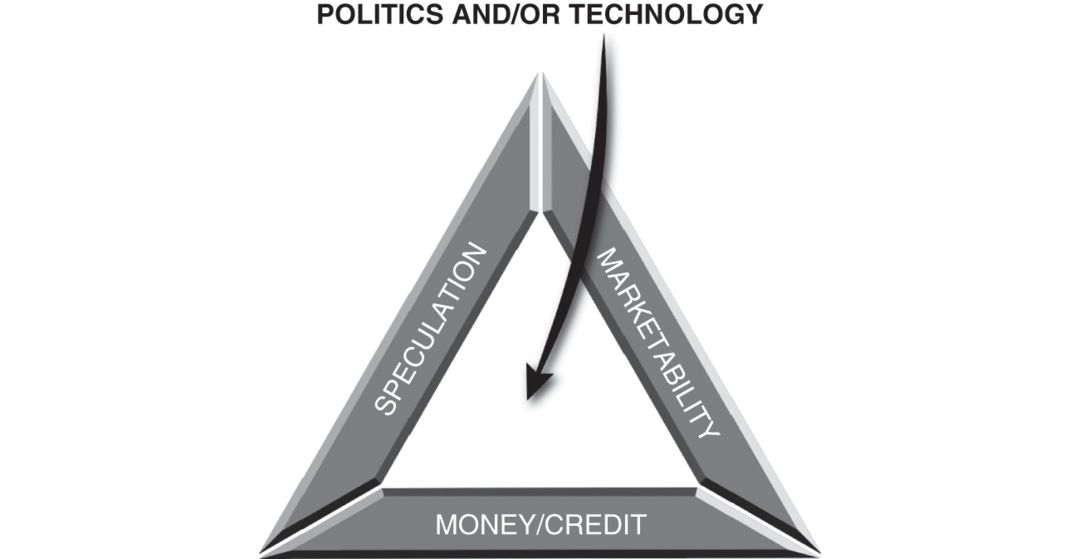

The Bubble Triangle

.

Figure 1.1

The bubble triangle

The first side of our bubble triangle, the oxygen for the boom, is marketability: the ease with which an asset can be freely bought and sold. Marketability has many dimensions. The legality of an asset fundamentally affects its marketability. Banning the trading of an asset does not always make it wholly unmarketable, as demonstrated by the abundance of black markets around the world. But it does usually make buying and selling it more difficult, and bubbles are often preceded by the legalisation of certain types of financial assets. Another factor is divisibility: if it is possible to buy only a small proportion of the asset, that makes it more marketable. Public companies, for example, are more marketable than houses, because it is possible to trade tiny proportions of the public company by buying and selling its shares. Bubbles sometimes follow financial innovations, such as mortgage-backed securities, that make previously indivisible assets in this case, mortgage loans divisible.