Bruns - Are filter bubbles real?

Here you can read online Bruns - Are filter bubbles real? full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Polity Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Are filter bubbles real?: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Are filter bubbles real?" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Are filter bubbles real? — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Are filter bubbles real?" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Axel Bruns, Are Filter Bubbles Real?

Milton Mueller, Will the Internet Fragment?

Neil Selwyn, Should Robots Replace Teachers?

Neil Selwyn, Is Technology Good for Education?

AXEL BRUNS

polity

Copyright Axel Bruns 2019

The right of Axel Bruns to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2019 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-3646-7

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

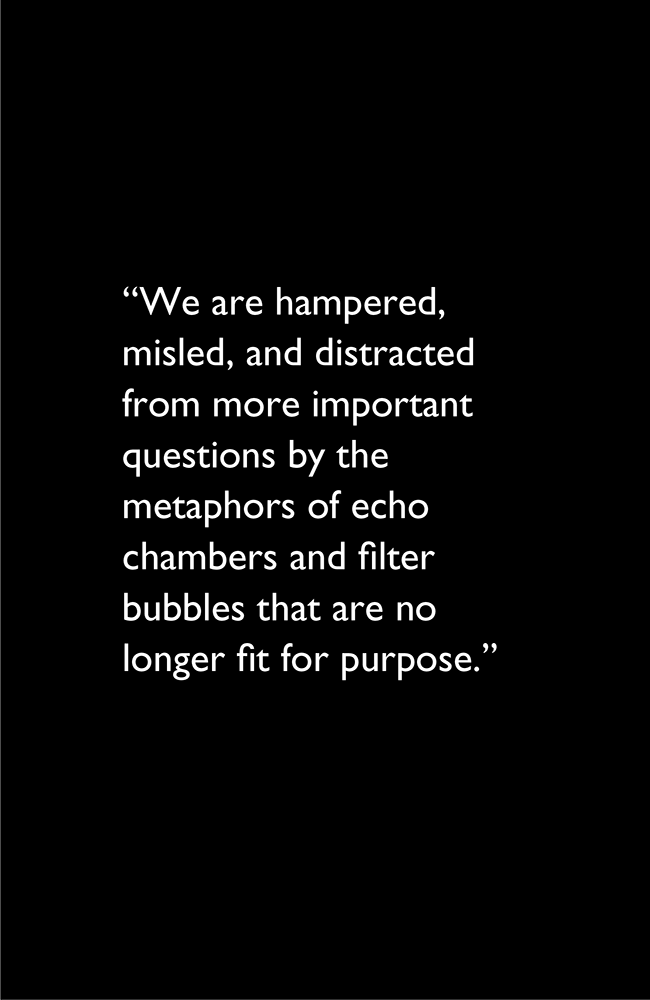

This book emerged as an unexpected companion to my 2018 monograph Gatewatching and News Curation: Journalism, Social Media, and the Public Sphere. As I wrote that book, it became increasingly clear how much we are hampered, misled, and distracted from more important questions by the metaphors of echo chambers and filter bubbles that are no longer fit for purpose, and probably never were. From my conversations at the Association of Internet Researchers, International Communication Association, Social Media & Society, and Future of Journalism conferences, I know that many of my colleagues feel the same.

If, like me, youre fed up with these vague concepts, based on little more evidence than hunches and anecdotes, this book is for you; if you think that theres still some value in using them, I hope I am at least able to introduce some more specific definitions and empirical rigour into the debate. In either case, perhaps I will convince you that the debate about these information cocoons distracts us from more critical questions at present.

My sincere thanks to the many colleagues with whom Ive discussed the themes of this book in particular, my colleagues in the Digital Media Research Centre at Queensland University of Technology. Many thanks also to Mary Savigar at Polity for a number of stimulating discussions about the shape of the book. My research was supported by the Australian Research Council Future Fellowship project Understanding Intermedia Information Flows in the Australian Online Public Sphere, Discovery project Journalism beyond the Crisis: Emerging Forms, Practices and Uses, and LIEF project TrISMA: Tracking Infrastructure for Social Media in Australia.

Introduction: More than a Buzzword?

As they leave the White House, outgoing US Presidents reflect on their experience. In 1961, Dwight D. Eisenhower used his final television address to warn of the grave implications of the powerful military-industrial complex that as a former World War Two general and Supreme Commander of NATO he had himself helped to create. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry could act as a corrective and control to the unwarranted influence of the military-industrial complex (1961: 23); though the Cold War has ended, his warning resonates still.

Barack Obamas farewell speech in Chicago on 10 January 2017 warned of a different danger, similarly requiring attention from an alert and knowledgeable public: amidst increasingly heated and uncivil political discourse, he suggested, for too many of us its become safer to retreat into our own bubbles, whether in our neighbourhoods, or on college campuses, or places of worship, or especially our social media feeds, surrounded by people who look like us and share the same political outlook and never challenge our assumptions (Obama 2017: n.p.). Like Eisenhower, Obama should know a good deal about this topic: after all, with his own online community site my.barackobama.com and later with mainstream platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, he is widely recognised as the first US President to successfully use social media in election campaigning.

Obamas concerns are far from new, however. Under labels such as echo chambers and filter bubbles, they are held responsible for a broad variety of social and political problems. Social media and the content filtering and recommendation algorithms they rely on have been identified as one reason that such phenomena have emerged; before them, search engines and the overall multiplication, fragmentation, and personalisation of available media sources in the Internet age were also highlighted as contributing factors. Put simply, the argument goes, if we all disappear into our different information cocoons, where we only ever encounter like-minded others and are served a highly selective media and information diet, then society fragments. Worse still, because it requires a well-informed citizenry and cross-ideological dialogue to reach a broadly supported consensus about the future direction of the state, democracy itself falters.

This book addresses these concerns and reviews the evidence for and against echo chambers and filter bubbles (in search, social media, and beyond). Ultimately, it argues that such fears about the societal effects of disconnected informational spaces, and about the role of new media technologies in their creation, only divert our attention from the much more critical question of what drives the increasing polarisation and hyperpartisanship in many established and emerging democracies.

Obamas warning followed Donald Trumps surprise victory in the US presidential election in November 2016; it mirrors similar concerns after the UKs Brexit referendum in June 2016, and other apparently unexpected wins for populist causes and candidates, despite widespread coverage of their personal and policy flaws. Politicians, journalists, and scholars who support the echo chamber or filter bubble thesis suggest that, with online and social media as the key sources of information for an ever-growing percentage of the public, it became possible for citizens to be locked into ideological filter bubbles that lacked cross-cutting information (Groshek and Koc-Michalska 2017: 1390). Brexit supporters might never have seen the warnings of the disastrous economic, social, and political consequences of exiting the European Union; Trump followers might not have encountered reports of the candidates personal flaws or the campaigns collusion with foreign powers.

Away from these momentous occasions, echo chambers and filter bubbles are also held responsible for the emergence of many more communities that espouse contrarian and counterfactual perspectives and ideologies. These include comparatively harmless conspiracy theorists compiling evidence of alien visitations; groups of agitators who steadfastly deny the reality of anthropogenic climate change or the benefits of population-wide vaccination; and extremists preaching racism, homophobia, and religious intolerance. The argument is that echo chambers enable these groups to reinforce their views by connecting with like-minded others, and that filter bubbles shield them from encountering contrary perspectives.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Are filter bubbles real?»

Look at similar books to Are filter bubbles real?. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Are filter bubbles real? and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.