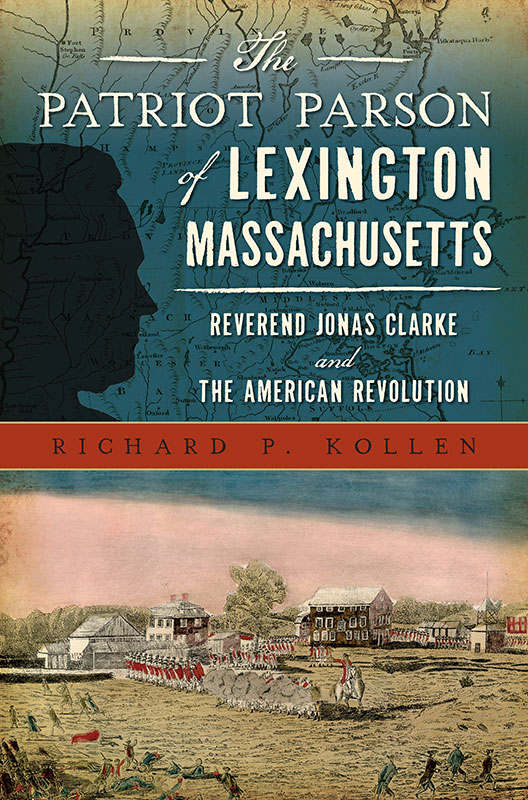

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2016 by Richard P. Kollen

All rights reserved

Cover image of Hancock-Clarke House by Paul Doherty.

First published 2016

e-book edition 2016

ISBN 978.1.62585.809.2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015955758

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.538.2

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Several organizations and individuals were critical to this book. I would especially like to thank Susan Bennett and Elaine Doran of the Lexington Historical Society. As society director, Susan supported the book and offered advice from its inception. I always had easy access to manuscript materials and images because of Elaine Doran, society curator. Susan Bennett, Mary Keenan, Mary Fuhrer and Philip McFarland all read the book at various stages and provided feedback that I incorporated in the manuscript. Ben Carp and Richard D. Brown were helpful at the beginning stages. This project also benefited from the manuscript collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, the American Antiquarian Society and the Arlington Historical Society. Acquisitions editor Stevie Edwards and production editor Ryan Finn at The History Press guided skillfully the project to its completion. Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Yinnie, for always encouraging my work.

This publication was made possible, in part, by the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati.

PROLOGUE

The sun had started its descent on April 19, 1775, as Reverend Jonas Clarke returned to the meetinghouse with his wife, Lucy, with a baby in her arms, and their eleven-year-old daughter, Betty. Earlier that day Lucy, baby Sarah and the other Clarke children, nine living at home in all, had desperately scattered into the woods; the youngest were hurried thirty miles away to their grandfather Thomas Clarkes house in Hopkinton, Massachusetts. Jonas Clarkes houseguests at the time, Whig leaders Samuel Adams and John Hancock, along with Hancocks fiance and aunt (all alerted by couriers Paul Revere and William Dawes), had already fled to neighboring Woburn.

That same dawn, British Regulars, hoping to travel undetected from Boston to Concord to seize rebel arms and stores, had marched as far as Lexington, where they encountered the town militia parading on the Common in a show of force. The British set about to disperse them. A bloody skirmish ensued, and eight men, seven of Lexingtons own, perished near Reverend Clarkes meetinghouse. Clarke had observed the action standing outside his parsonage no more than four hundred yards from the Common. When the firing ended, the Regulars marched on toward an already alerted Concord.

By two oclock that afternoon, thirsty and exhausted British troops were staggering back through Lexington in a desperate flight to the safety of Boston. Fortunately for them, a relief mission led by Colonel Earl Percy had set up a rear-guard action near Munroe Tavern to cover their retreat. But before the British passed on through Lexington, they inflicted further scars. A cannonball tore through the roof of the meetinghouse, Munroe Tavern was damaged and three private homes were torched.

Some of the militia from surrounding towns who had pursued the Regulars from Concord as far as Lexington now drifted over to Reverend Clarkes parsonage and partook of the provisions he offered them. Around four oclock in the afternoon, the minister gathered remnants of his family still in town and grimly headed toward the meetinghouse. Clarke had earlier sent his son Jonas to Menotomy (today Arlington) to check with Reverend Samuel Cooke on the death toll there. Now the time had come to reckon the price Lexington had paid.

Reverend Clarke stood in front of eight caskets stacked one on top of the other inside the meetinghouse and prayed. His parish had just endured a gut-wrenching tragedy. Deeply saddened at the loss of life, the minister was furious at the British Regulars, although he fully understood his part in what had happened. Clarke had been a pivotal actor in the events of the fateful day, even if he had not physically stood with his parishioners on the Common while the British Regulars rushed at them, bayonets glinting in the rising sun. Warned of British plans, he had consulted with his houseguests Samuel Adams and John Hancock as to the proper course to follow. Beyond that, he had for years guided his parish toward opposing imperial legislation, thus contributing to the hostile environment that had led the British to send their expedition to Concord. A pastor of decidedly independent sensibilities, Reverend Clarke maintained a Whig parish through the formidable power of his office. Beyond his leadership from the pulpit, through writing town meeting resolutions and instructions to the town General Court representative, the colonys legislative body, he had shaped Lexingtons response to the tightening vise of new laws imposed by Parliament. With this history behind him and although pained by the deaths of his parishioners and other Massachusetts colonists later in this fateful day, Clarke remained convinced that the recent struggles served a larger purpose.

Events of April 19, 1775, lit the spark that set in motion a course leading to the independence of the United States. Jonas Clarke, through an accident of geography, through marriage, through his own sense of responsibility and through faith in divine providence, played a major role in what came to pass. Like many country ministers of the time, his work has gone largely unnoticed in histories of the Revolution. Even Loyalist Peter Olivers often quoted pejorative reference to the black regiment was directed at Boston ministers whom he knew. Reverend Charles Chauncy, Reverend Jonathan Mayhew and Reverend Samuel Cooper have enjoyed historical recognition for their leadership in Boston. But Whig country ministers have more often been treated as anonymous abstractions, rarely singled out for their significant contributions.

A simple country minister, Reverend Jonas Clarke certainly rose in prominence once the battle rent his town. But the skirmish on Lexington green would not have occurred without Clarkes critical work in preparing the ground for resistance. An ordinary man in extraordinary times who found himself at a historical crossroad, he chose to follow the path that led to revolution.

Chapter 1

BEGINNINGS

Today, a birth to a Christian family on December 25 would deepen, if not overwhelm, its holiday celebrations. But Jonas Clarkes arrival in Newtown (Newton), Massachusetts, on December 25, 1730, competed with no festive observances. Congregational communities still largely condemned Christmas celebrations as pagan rites associated with postharvest saturnalia. Some rowdy behavior might have occurred on the fringes of Boston social life, but orthodox Calvinists still had little use for English Christmas traditions as practiced then. Instead, residents of Newtown and its environs went about their activities on the day of Jonas Clarkes birth as on any other Friday. For Thomas and Elizabeth Clark, a new son brought profound joy to the household. Even so, they could hardly have imagined their sons significant role in severing ties with a government overseas to which they paid loyal homage.

Next page