MARY LOUISE ROBERTS

D-DAY THROUGH FRENCH EYES

Normandy 1944

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

Mary Louise Roberts is professor of history at the University of Wisconsin and the author of What Soldiers Do: Sex and the American GI in World War II France, Disruptive Acts: The New Woman in Fin de Sicle France, and Civilization without Sexes: Reconstructing Gender in Postwar France, 19171928.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London 2014 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2014.

Printed in the United States of America

23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-13699-8 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-13704-9 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226137049.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Roberts, Mary Louise, author.

D-Day through French eyes : Normandy 1944 / Mary Louise Roberts.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-226-13699-8 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-226-13704-9 (e-book)

1. World War, 19391945CampaignsFranceNormandyPersonal narratives, French. I. Title.

D756.5.N6R595 2014

940.54'21421092dc23

2013040601

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For Sue

CONTENTS

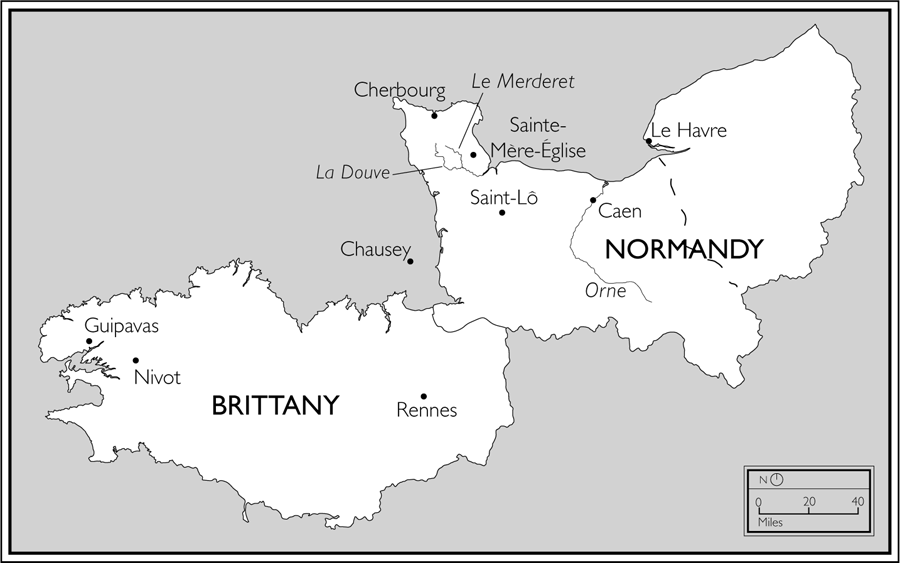

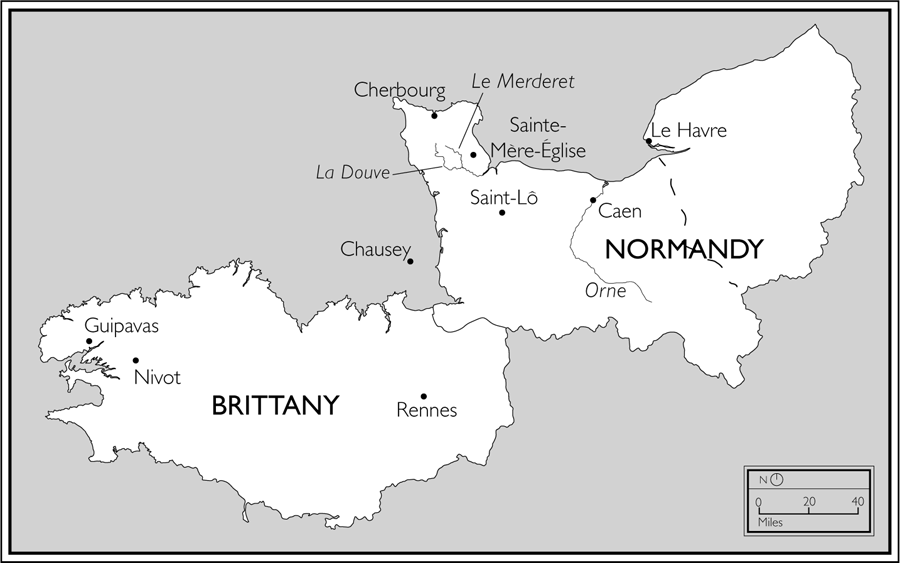

FIGURE 1a. Map of Brittany and Normandy, France.

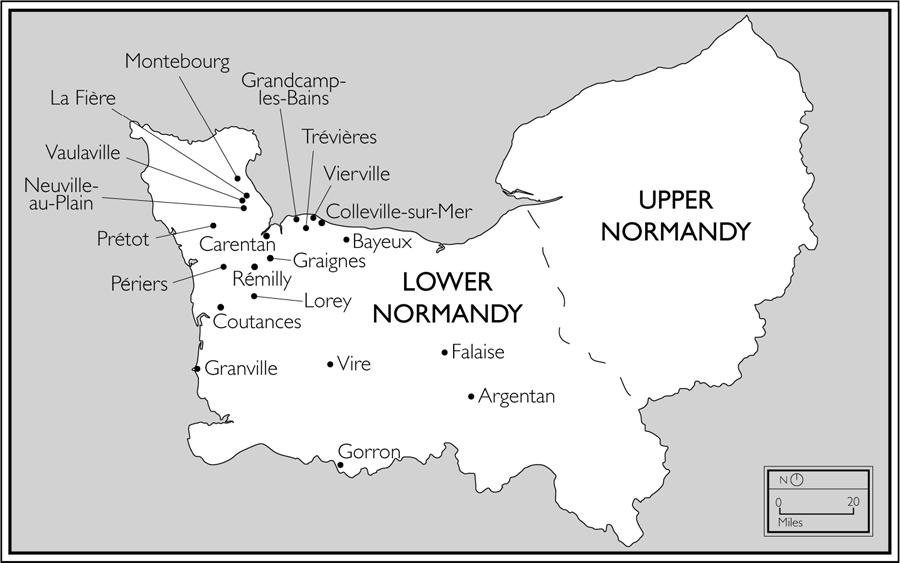

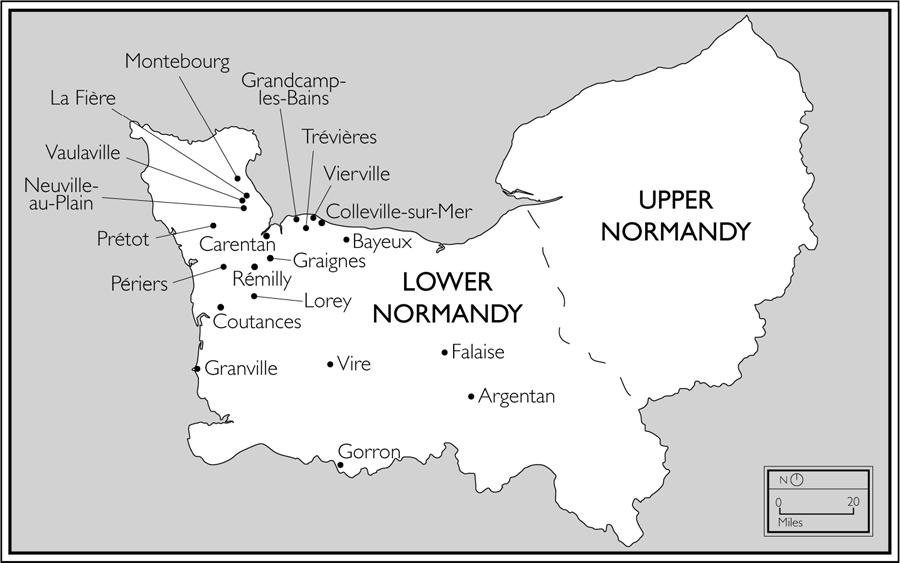

FIGURE 1b. Map of Normandy.

INTRODUCTION

At the mention of D-Day, most Americans summon the image of GIs landing on Omaha Beach in Normandy, France. These first steps onto Nazi-occupied soil, immortalized in a photograph often attributed to Robert Capa, dominate our perceptions of World War II. But did you ever wonder how the landings looked from the opposite directionto the French onshore? What was D-Day like for the Normans?

US historians have told and retold the story of the Normandy Invasion. But in most accounts, the focus remains on the day-to-day fighting of the Allied forces, particularly the American GIs. As a result, the experience of the Normans has been almost completely ignored. To remedy this, the collection of documents gathered in this book will widen our view by presenting D-Day and the Normandy Campaign through French eyes. Among these documents are tmoignages, or testimonies, of the campaign culled from French archives and publications.

While acknowledging the British and Canadian contributions to the Normandy Campaign, I have selected testimonies that focus on the American experience of battle. Besides wanting to reach a specifically American audience, I felt the need to limit the project in some way, given the outpouring of memoirs since the fiftieth anniversary of the landings. I have chosen tmoignages that revolve

FIGURE 2. The GIs land on the shores of Normandy.

The Normandy Invasion, also known as Operation Overlord, has become so famous as to hardly need an introduction. The campaign began on D-Day, June 6, 1944, in the fifth year of World War II, the most immense and costly war in history. By 1944, the US military had been deployed in two separate theaters. In the Pacific theater of operations, the GIs were fighting the Japanese, who had attacked the United States in December of 1941. In the European theater, the GIs joined the British and Canadian armies to fight the Germans, whose military aggression had begun in 1939 against Poland. At the peak of Hitlers power in 1942, his forces occupied much of Europe, North Africa, and the Soviet Union.

The German conquest of France in the spring of 1940 led to the creation of a French collaborationist state known as the Vichy regime. The Nazis divided the French nation into two zones, roughly split between north and south. In the southern free zone, the Vichy government maintained sovereignty under the leadership of Philippe Ptain. In the northern occupied zone, which included the entire western coast, Ptains collaborationist state retained only limited authority. The German Wehrmacht maintained a strong presence there in anticipation of an Anglo-American invasion along the Atlantic coast. This dual-zone structure collapsed in November 1942, when Allied forces created a new front in northern Africa. At this time, the Germans occupied all of France.

Ptain justified his collaborationist state on the grounds that it would save the French from the worst excesses of German rule. In fact, it did not. Under the guise of occupation costs, the Nazis drained France of every natural resource as well as food and other basic necessities. Two million Frenchmen were detained as prisoners of war, forced laborers, and deportees. Jews and other undesirables were persecuted, then deported east; most did not return. Following the liberation of the country in 1944, the exiled general Charles de Gaulle emerged to claim national sovereignty for the French. Vichy officials fled, were arrested, or were summarily shot by local Resistance forces. Ptain was sentenced to death for treason. For the French people, then, the Liberation was joyful but also chaotic and confusing. Besides the devastating effects of a war fought on their own soil, they had to deal with political uncertainty and the shame of collaboration as well as the humiliation of diminished national prestige.

For the Allies, by contrast, Normandy was a moment of triumph. The Americans first joined forces with the British and the Canadians against the Germans in North Africa in late 1942. After a terrible struggle in the Tunisian desert, these Allied forces established a foothold there. In July 1943, they moved northward to conquer Sicily, and in September of that year began a long, very difficult campaign for continental Italy. Their efforts in France would succeed rapidly by comparison. Although the Allies met fierce German resistance in Normandy, they were in Paris by the end of August, ten weeks after the invasion began. By contrast, Rome eluded liberation for a full nine months after they first stepped onto southern Italian soil. Although the road from Paris to Berlin was no easy journey, they triumphed over the Germans within a year of the landings. By August 1945, the Americans, along with the British and Canadian forces, were victorious in both the European and the Pacific theaters of war. The United States stood, to use Churchills phrase, at the summit of the world.

The wars outcome, then, was glorious for the Americans and humiliating for the French. This difference in fates between the two nations has shaped how US historians have told the story of Normandy. In most American accounts, the French are almost completely left out of the picture, appearing only at the peripheries of the campaign. The contributions of the French army and the organized civilian Resistance are dramatically underplayed. Although General Dwight Eisenhower equated the effectiveness of the Resistance in Normandy with a full fifteen military divisions, French civilians are portrayed nonetheless as inert bystanders at their own liberation.

In fact, Normans were far from passive observers. They participated far more in the battle than has been recognized by US historians. They also suffered more. The first two days of the invasion alone resulted in three thousand deaths, a figure equaling Allied losses during this period.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).