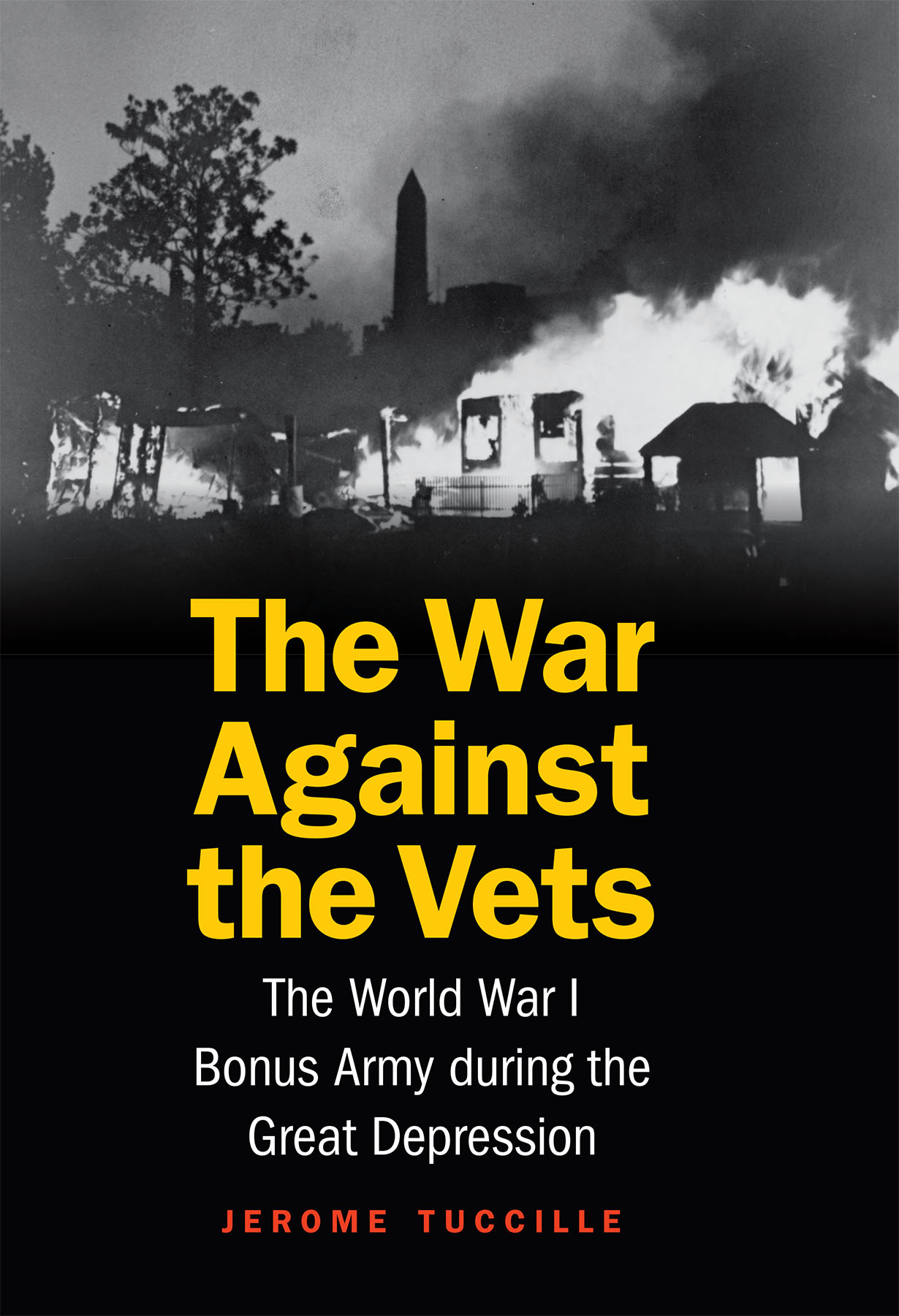

In this meticulous and engrossing book, Jerome Tuccille sheds new light on a truly shameful chapter in American history.

The War Against the Vets

The World War I Bonus Army during the Great Depression

Jerome Tuccille

Potomac Books

An imprint of the University of Nebraska Press

2018 by Jerome Tuccille

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover image courtesy the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-115563.

Author Photo Wendi Winters.

All rights reserved. Potomac Books is an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tuccille, Jerome, author.

Title: The war against the vets: the World War I Bonus Army during the great Depression / Jerome Tuccille.

Description: Lincoln: Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017043080

ISBN 9781612349336 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 9781640120662 (epub)

ISBN 9781640120679 (mobi)

ISBN 9781640120686 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : Bonus Expeditionary Forces. | World War, 19141918VeteransWashington (D.C.) | Protest movementsWashington (D.C.)History20th century. | Washington (D.C.)History20th century. | VeteransPolitical activityUnited StatesHistory20th century. | VeteransUnited StatesEconomic conditions20th century.

Classification: LCC F 199 . T 83 2018 | DDC 973.91/6dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017043080

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

This book is dedicated to the American veterans who risked their lives for their country, only to return to an uncaring public and a government that paid them only lip service for their sacrifice.

Contents

Two great American writers bookended the long, tragic story of the World War I bonus marchers in the early years of the Great Depression. At the beginning of the saga a seven-year-old boy named Gore Vidal sat in the back seat of a car beside his blind grandfather, Sen. Thomas P. Gore, one of Oklahomas first two senators. The boy stared out the window, searching diligently for signs of the Boners he had been hearing about for weeks on end. In his minds eye he envisioned the Boners as looking like preternatural freaks, cardboard ones displayed at Halloween. Bony figures filled my nightmares until it was explained to me that these Boners were not from slaughterhouses but from poorhouses, he wrote later.

What Vidal saw instead was a long stream of shabby-looking men holding up signs and shouting at occasional cars. Moments later a stone hurled by one of the demonstrators flew through the open window of the car and crashed on the floorboard between the boy and his grandfather. Shut the window! the senator shouted, a command the boy obeyed immediately. The chants of the ragged, homeless, and penniless men filled the future authors ears as the chauffeur maneuvered the vehicle through the encroaching mob. The Yanks are starving! The Yanks are starving! they sang to the tune of a popular war song of the era.

Three years later the thirty-six-year-old world-famous author Ernest Hemingway decried the deaths of several hundred World War I vets and their families, whose lives were literally blown away during the most devastating hurricane ever to blast the Florida Keys. by the water, swollen and stinking, their breasts as big as balloons, flies between their legs. Who left you there? And whats the punishment for manslaughter now? Hemingway wrote. He put the blame on the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, which was responsible for shipping the vets out of the nations capital, where they had regrouped to demand their unpaid bonuses as they had done in 1932, when Herbert Hoover was still in the White House.

In between Vidals and Hemingways moving eyewitness accounts, one of the sorriest chapters in American history unfolded in the makeshift campsites the vets had erected along Pennsylvania Avenue, which linked the executive and legislative branches of the federal government. The drama that played out exploded like a bombshell at the very focal point of American political life.

Before there was the Bonus Army there was Coxeys Army. Before there was the Great Depression there was the Panic of 1893, when the unemployment rate in America soared to a staggering 18 percent. And before Gore Vidal and Ernest Hemingway emerged to describe the travesty of justice that befell the Bonus Army of the 1930s, an earlier American writer named Jack London wrote about his own experiences marching with Kellys Army, a group affiliated with Coxey, to demand work for unemployed stiffs, as he called them.

and maidens came out to meet us, and the good citizens turned out by hundreds, locked arms, and marched with us down their main streets.

The march took shape when an Ohio businessman and thoroughbred racehorse breeder named Jacob Coxey staggered to the brink of bankruptcy in the wake of the financial panic of 1893. The American economy had been prone to a series of boom-and-bust cycles throughout its century-long history, and this latest bust hobbled Coxey, undermined his local fiefdom, and sent him into a boiling rage. Virtually overnight as it were, his once prosperous limestone quarries lost most of their value, and Coxey was forced to fire about forty of the workers he employed in his family enterprise. his role as the employer of dozens of local laborers and setting himself up as a firebrand leader of Americas growing army of the downtrodden and unemployed.

His timing could not have been better. The country was ready for just such a leader, a strong man championing peoples rights to a job that paid them enough to clothe, feed, and shelter themselves and their families. Coxey called for an army of the disenfranchised to march to the nations capital to demonstrate in favor of a national public works project that would be financed by government bonds and an infusion of capital into the system. If he got his way Coxeys Army would be put to work rebuilding the infrastructure, particularly the roads, projects dear to the hearts of midwestern farmers, who demanded serviceable roads to get their produce to the markets. Coxeys Army began its march from Massillon, Ohio, on March 25, 1894, with an initial contingent of one hundred men. Other armies quickly joined his cause in different regions of the country, including one from the West headed by self-styled General Charles T. Kelly. Kellys Army, the one that claimed Jack London among its ranks, lost most of its members by the time it reached the Ohio River, and London seemed to have treated it more as a larkfodder for his storiesthan anything else.

Coxey and many of his imitators, however, were determined to get their voices heard in Washington DC . Their plan was to arrive a flamboyant westerner named Carl Old Greasy Browne, who considered several exotic ideas to be Gospel Truth.

The foremost idea in his head was that a man should never bathe or change his clothing. Attired as he was in an outfit modeled after that of Buffalo Bill Cody and sporting a shock of filthy, tangled hair, Browne presented an image that was nothing short of exotic, to say the least, and he exuded a pungent odor that announced his presence before he entered a room. A second idea he held to be sacred was a belief in reincarnation. He thought that everyone was born over and over again with a dash of Jesus Christ nestled in his genes. And a third notion, which underscored and compounded the second idea, was that Jacob Coxey had a dollop more of Jesus in him than most mere mortals did. Indeed, Browne told Coxey that he was the Cerebrum of Christ. Coxey, a committed agnostic until this point, allowed Brownes canonization to stroke his ego. He accepted his sainthood without giving it much thought and renamed his army the Commonweal of Christ at Brownes suggestion. Unfortunately, if there had ever been a chance that Coxey would succeed in attaining his goals in Washington, he managed only to turn his crusade into a circus sideshow with Browne marching beside him.