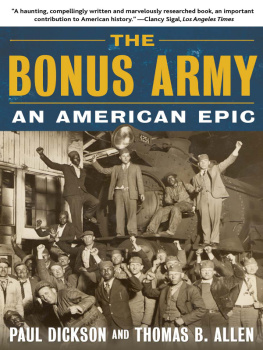

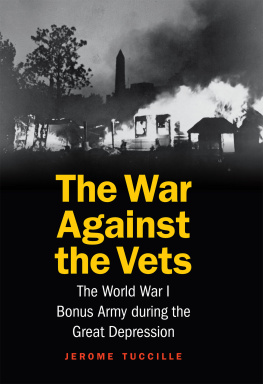

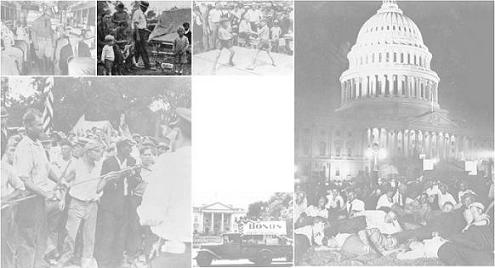

The

Bonus

Army

An American Epic

Paul Dickson and

Thomas B. Allen

Walker & Company, New York

History is littered with governments destabilized by masses ofveterans who believed that they had been taken for fools by asociety that grew rich and fat at the expense of their hardshipand suffering.

Anthony J. Principi, U.S. Secretary of Veterans Affairs, alluding to the Bonus Army in a March 14, 2001, speech to the Smithsonians Wilson Library on Veterans as Revolutionaries

Contents

O NE NIGHT toward the end of May 1932, Pelham Glassford, the police chief of Washington, D.C., was driving south from New York City through New Jersey when suddenly in his headlights appeared what he later described as a bedraggled group of seventy-five or one hundred men marching cheerily along, singing and waving at the passing traffic. One man carried an American flag and another a banner that read, Bonus or a Job. Atop a pushcart, an infant girl lay sleeping, nestled amid one familys clothes. Glassford pulled over.

He later wrote that the group cheered upon seeing his District of Columbia license tags. And when I stopped, they gathered around with many questions on their possible reception, on the road they should take. They asked him to join them. He declined and they handed him a leaflet entitled DontLet the Bankers Fool You. A marcher urged him to give a copy to President Herbert Hoover.

For the previous several days, newspapers across the nation had been carrying accounts of marchers bound for the nations capital. The demonstrators were part of a growing army of veterans and their families heading to Washington from across the country to collect payment of the bonus, promised in 1924 to soldiers who had served in the Great War, but deferred until 1945 because of wrangling over the federal budget. Now, deep in the Depression, the vets had dubbed the delayed payment the Tombstone Bonus, for the only way to get the cash before 1945 was to die, in which case the payment would be made to the next of kin as a death benefit.

In 1932, a year in which unemployment had soared to almost 25 percent, leaving roughly one family out of every four without a breadwinner, two million people wandered the country in a futile quest for work. But unlike most of the men, women, and children on the move, the veterans knew where they were going and why they were going there. Washington was a goal, a place to stay while they lobbied Congress for immediate payment of their bonus.

Glassford, who had become the U.S. Armys youngest field grade brigadier general in 1918 during the Great War, had been police chief for only six months. Hired to put a professional shine on a police force tarnished by corruption and the lawlessness fostered by Prohibition, he had already twice dealt with angry demonstratorsin the Communist-led Hunger March in December 1931 and, a month later, during a march against unemployment by about ten thousand jobless men and women led by a Pittsburgh priest. But the veterans march was different. They were going to Washington to lobby for what theyand many in Congressfelt was their due.

Victorious war veterans have vexed politicians since the days of Caesars legions. Returning warriors were both a potential power bloc and a threat men who marched off to serve the state in war and then straggled back in peacetime, brewing discontent and looking for rewards. The Romans established the Aerarium Militare, the first veterans bureau, to deal with the ex-soldiers who demanded pensions and balm for their wounds.

In Elizabethan times, discharged soldiers and sailors became beggars and highwaymen. London ironically invoked martial law to cope with the warrior mobs. A royal proclamation threatened summary executions for mariners, soldiers, and masterless men who did not leave London immediately.

In colonial Americas earliest days, recognition was given to wounded soldiers. In a proclamation of 1636, the leaders of the Plymouth Colony of Massachusetts declared, If any person shall be sent forth as a soldier and shall return maimed he shall be maintained competently by the Colony during his life. Early in the Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress provided pensions for both disabled veterans and the dependents of soldiers killed in battle. The last surviving dependent of the Revolutionary War continued to receive benefits until 1911.

But what of the men who return whole? Even as noble a cause as the American Revolution ended with a disgruntled army, menacing the politicians.

After the British surrendered at Yorktown in 1781, rumors spread through-out the ranks that the Continental Army would be demobilized without being paid. In June 1783, a small band of soldiers from the unit known as the Pennsylvania Line marched on the capital of the new nation in Philadelphia, demanding the back pay owed to them. They surrounded the State House and poked their bayonet-tipped muskets through the windows at the assembled Congress, which included such members as James Madison and Alexander Hamilton. When the governor of Pennsylvania, who was in attendance, was asked to call for his militia, he said he would not be able to protect Congress because he could not count on his militia to follow his orders. Fearing a coup dtat, Congress quit the building, pushed through the jeering armed mob, and headed to Princeton, New Jersey.

For weeks the soldiers held their ground. They grew into a mutinous mob of four hundred, making daily demands on the government and terrorizing the citizens of Philadelphia. Finally, after weeks of the renegade soldiers daily demonstrations and threats, George Washington sent a force of fifteen hundred Continental soldiers to compel the men to return to their homes. Two of the leaders of the mutiny were sentenced to be shot, led out to be executed, and faced a line of soldiers with loaded guns. At the last minute they were pardoned by Congress. Other leaders were whipped before being released.

The Revolutionary War mutinies were not about power or ideology but simply about being paid for services rendered. They would establish what became a social contract between the nation and those who fight its battles: when a war ends, members of the military must be paid in full for their service. Although most Revolutionary War veterans were not paid for years, most eventually got back pay and pensions.

The mutiny had another consequence. During the Revolutionary War, Congress had retreated three times from Philadelphiafirst to Baltimore, then to Lancaster, and then to Yorkto avoid capture by the British. But Congress had always returned to Philadelphia. After the 1783 mutiny and the humiliating departure, the members vowed never to return. They stayed at Princeton until the end of the year, then moved to Annapolis, followed by Trenton, and finally to New York.

When the Constitutional Convention met in 1787, memories of 1783 were still so fresh in the delegates minds that they wrote a provision into the Constitution, providing for a new kind of capitala federal enclave, which would become Washington, D.C., by the turn of the century.

Just as mutinous veterans of the Revolution had had enough power to move the capital, veterans of the Great War, by marching on that capital in 1932, were able to move the nation to a new social contract that is still valid today.

Next page