The Story of the Home Guard

NORMAN LON G MATE

AMBER LEY

This edition first published in Great Britain 2010

Copyright Norman Longmate 2010, 2011, 2012

This electronic edition published 2012 by Amberley Publishing

Amberley Publishing

The Hill, Stroud

Gloucestershire, GL5 4EP

www.amberleybooks.com

The right of Norman Longmate to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

eISBN 978-1-4456-0878-5

Visit www.amberleybooks.com to find out more about our books, authors and special offers.

CONTENTS

The first day I got my uniform the missus looked at me and she said. What are you supposed to be? I said, Im one of the Home Guards. She said, What are you supposed to do? I said, Supposed to do, I supposed to stop Hitlers army landing. She said What, YOU? I said No, not me, theres Billy Brightside, Charlie Evans and Joe Battersb y , theres seven or eight of us. W ere on guard on a little hut behind the Dog and Pullet. She said, I suppose that was your idea? I said, Y es, and that Charlie Evans wants to claim it as his.

ROBB WI L TON in radio sketch, The Day I Joined the Home Guard

It began, like the war itself, with a broadcast. On the evening of T uesday 14 May 1940 the newly-appointed Secretary of State for W a r , Anthony Eden, appeared on the BBC Home Service. Four days earlie r , on the previous Frida y , the Germans had begun their long-awaited offensive in the W est and already alarming reports of their success, and the unexpected methods they had used to achieve it, were reaching Britain, as Eden explained:

I want to speak to you tonight about the form of warfare which the Germans have been employing so extensively against Holland and Belgium namely the dropping of parachute troops behind the main defensive lines. In order to leave nothing to chance, and to supplement from sources as yet untapped the means of defence already arranged, we are going to ask you to help us in a manner which I know will be welcome to thousands of you. Since the war began the government have received countless enquiries from all over the kingdom from men of all ages who are for one reason or another not at present engaged in military service, and who wish to do something for the defence of their countr y . W ell, now is your opportunit y .

W e want large numbers of such men in Great Britain, who are British subjects, between the ages of seventeen and sixty-five to come forward and offer their services. The name of the new force which is now to be raised will be The Local Defence V olunteers. This name describes its duties in three words This is a part-time job , so there will be no need for any volunteer to abandon his present occupation. When on duty you will form part of the armed forces. Y ou will not be paid, but you will receive a uniform and be armed. In order to voluntee r , what you have to do is give in your name at your local police station; and then, as and when we want you, we will let you kno w .

And so, in between the 9 oclock news and a documentary programme The V oice of the Nazi on the BBC, was launched the largest, strangest and if the truth be told least military volunteer army in Britains long histor y . For the W ar Minister had been right. Not thousands but hundreds of thousands of men were not merely willing but eager to have a crack at Hitle r , whom most people in Britain regarded by now not only as the leader of Germany but as a personal enem y .

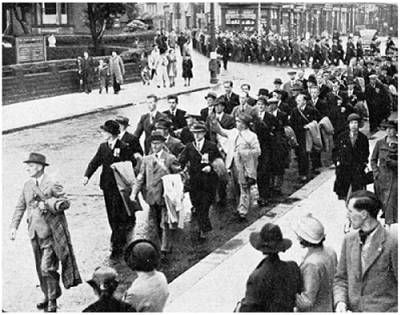

The rush to the colours began at once. One Y ork housewife remembers her husband going out without a word. Jumping on

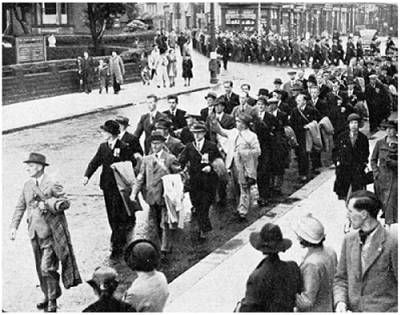

1. Scarborough volunteers demonstrate their readiness, June 1940.

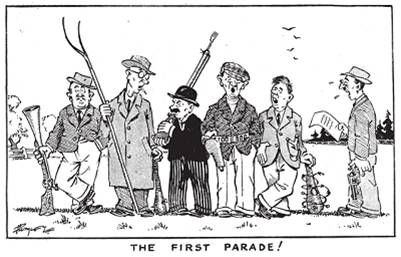

2. The first parade of the ramshackle LD V . From Home Guard Humour, 1944.

his motorcycle and roaring off two miles to the police station. But quick as he had been another man was there before him. At many other places the first applicants were round at the police station before Eden had finished speaking. The flood continued next morning, although the police were not always very welcoming, as the novelist Ernest Raymond, who had served in Gallipoli as an Army padre and was now an air raid warden at Haywards Heath in Sussex, discovered:

Enthusiastically resolved to be transformed from a civilian warden to a combatant of sorts I was at our police station after breakfast next morning. I confess I expected some praise for this promptitude, as I passed through the sandbag barrier that protected the stations doorwa y . It was not forthcoming. The uniformed policeman behind the desk sighed as he said, W e can take your name and address. Thats all. A detective-inspector in mufti, whom I kne w , explained this absence of fervou r . Y oure about the hundred-and-fiftieth whos come in so fa r , Mr Raymond, and its not yet half past nine. T en per cent of em may be of some use to Mr Eden but, lor luv-a-duck, weve had em stumping in more or less on crutches. W eve taken their names but this is going to be Alexanders rag-time arm y .

As I passed out through the sandbags I met three more volunteers about to file in through the crack. I knew them all. One was an elderly gentleman-farmer whod brought his sporting gun Another had his hunting dog with him;. All explained that they were joining up so I prepared them for the worst, I said, W ell, dont expect any welcome in there. They dont love us. And get it over quickl y . I rather suspected that if I stayed around too long, Id be arrested for loitering.

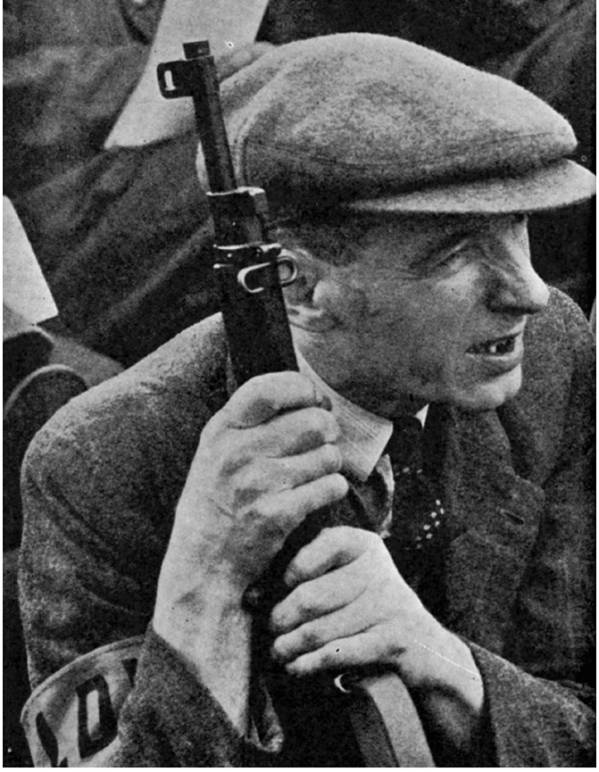

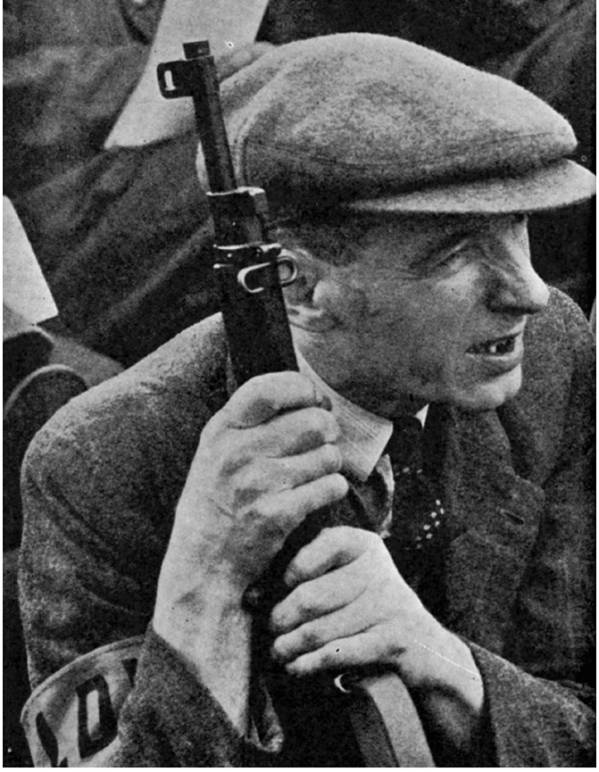

3. A Local Defence Volunteer.

Everywher e th e respons e wa s overwhelming . Thi s wa s th e experience of one ex-officer who had taken on the job of enrolling applicant s a t Canterbur y Roa d Polic e Statio n i n Perr y Ba r , Birmingham:

The weather was sweltering and we were allotted the small decontamination room in the police station yard. Applicants seemed to form a neve r -ending stream. They started to queue up as soon as they could leave their work and by 11 p.m. there were still scores of them waiting to enrol. Every night we worked until the small hours of the morning, trying to get some sort of shape into the organisation in preparation for the next days rush. W ithin a few days the platoon was three or four hundred strong and it seemed that if every police station were experiencing the same influx, all the male population in Birmingham would be enrolled within a week or two.

Over the country as a whole 250,000 men, equal in numbers to the peacetime Regular Arm y , gave in their names in the first twenty-four hours. The supply of enrolment forms soon proved inadequate. In Bideford, in Devon, where 240 volunteers had been expected and 1046 were to sign on by 1 August, a local resident and future LDV commande r , filled the gap by commissioning a local printer to copy the official form. Many enrolment forms were run off on an office duplicator or recruits signed a temporary slip promising to fill in the proper document when they got the chance. As the news grew worse, the desire to serve increased. On 17 June France surrendered and Britain stood alone. By the end of that month volunteers for the LDV numbered nearly one and a half million, not far short of the Armys wartime strengths, conscripts and all.

Next page