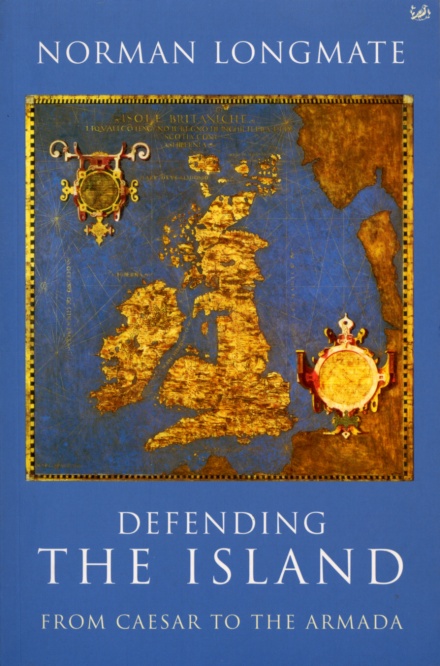

DEFENDING THE

ISLAND

From Caesar to the Armada

NORMAN LONGMATE

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 1.0

Epub ISBN 9781446475751

www.randomhouse.co.uk

Published by Pimlico 2001

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Copyright Norman Longmate 1989

Norman Longmate has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work

First published in Great Britain by

Hutchinson 1989

Pimlico edition 2001

Pimlico

Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V 2SA

Random House Australia (Pty) Limited

20 Alfred Street, Milsons Point, Sydney,

New South Wales 2061, Australia

Random House New Zealand Limited

18 Poland Road, Glenfield,

Auckland 10, New Zealand

Random House (Pty) Limited

Endulini, 5A Jubilee Road, Parktown 2193, South Africa

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

www.randomhouse.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 0-7126-6711-3

CONTENTS

BOOK 3: ENGLAND VERSUS ROME

DEFENDING THE ISLAND

Norman Longmate was born in Newbury, Berkshire, and educated by scholarship at Christs Hospital, where he was deeply influenced by an inspiring history teacher. After war service in the army he read modern history at Worcester College, Oxford. He subsequently worked as a journalist in Fleet Street, as a producer of history programmes for the BBC, and for the BBC Secretariat. In 1981 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and in 1983 he left the BBC to become a full-time writer.

Norman Longmate is the author of more than twenty books, mainly on the Second World War and on Victorian social history, and of many radio and television scripts on historical subjects. He has frequently been employed as an historical adviser by film and television companies.

FOREWORD

Fear of a foreign invasion of the British Isles has troubled the minds of successive generations of their inhabitants, and especially of Englishmen, for though the attack has often come through Wales, Scotland or Ireland England has always been the ultimate target. Throughout the sixteen and a half centuries covered by this volume the risk of invasion was ever-present and for much of it hardly a decade passed without an attack from the continent being either feared, contemplated, or attempted, while on the South Coast actual landings were at some periods almost an annual event. Limitations of space have inevitably defeated my original intention of recording, wherever possible in the words of contemporaries, every occasion on which any enemy has set foot on our shores, but I have none the less included far more, and described them in much greater detail, than any previous work in this field. (Most such books have, indeed, been very slight; and the last two-volume invasion history, on a much more modest scale than the present one, appeared more than a century ago.) Invasion I have defined as any operation which involves foreigners under arms landing on British soil against the wishes of the ruling government. This includes successful landings in force, followed by occupation and a change of ruler; major attacks ultimately followed by withdrawal; attempts which failed at an earlier stage, through military defeat or for other reasons; short-term raids, when an enemy spent only a few hours or days ashore; so-called tentatives, where elaborate preparations came in the end to nothing; and friendly invasions or invasions by invitation, when an enemy responded to an appeal for assistance from within the country, or a partly foreign army supported a claimant to the English throne. I have also covered a number of invasion alarms, which often involved as much dismay and disruption as real attempts.

Although invasions of the British Isles were often a consequence of English operations on the continent, and most weapons and military techniques relevant to invasions were developed primarily in foreign wars, or in internal rebellions and their suppression, the need to keep the text to a reasonable length has precluded dealing with these subjects in detail. I have, however, tried to explain as fully as space has allowed why invasions occurred, especially when they resulted not from the tedious squabbles between king and nobility of which so much medieval history consists, but from such causes as the English claim to the French throne or hostile relations between the ruling English sovereign and the papacy. I have thus found myself writing a far more wide-ranging book than the basically military history I had intended, while constantly being compelled to omit much interesting material on grounds of publishing practicality rather than irrelevance. I have tried none the less to retain, and to establish the truth of, some of the familiar legends associated with the invasion story, from Alfreds burning of the cakes to Drakes determination to finish his game of bowls. A truly comprehensive history of the invasions of England could easily rival in length Gibbons Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, which runs to around 1,350,000 words. Defending the Island, which will consist of two volumes of 200,000 words each, is by comparison distinctly slight, but is none the less four times the length of the single, short volume originally commissioned, and the research for the two volumes, and the writing of the first, have already taken some five years.

For most of the period covered here the language used by the chroniclers was not English and even when it did become the universal tongue it was far from standardized. The quotations in the earlier chapters have been translated into modern English, while those from around 1500, which can, with a little effort, be understood by the modern reader, have been retained in the original, though I have made some minor changes to improve readability, like substituting u for v where necessary. The original punctuation has also been altered where it seemed clumsy or misleading. In the case of names, of places and persons, which throughout this period were often rendered, even in the same sentence, in many different ways, I have opted for what seems the most generally accepted form, while giving the alternatives in parenthesis.

I have tried to identify, and indicate precisely in the text, the location of all the sites and villages mentioned, about which many previous writers have been remarkably vague. Except in the case of Wales, where the names then adopted could claim some earlier authority, I have used throughout the historic names of the counties during the period covered by this book, not those imposed on the country in 1974.

No proper calendar existed in England in the early years of the period covered by my story, and by the end most of Europe was using a different one from that in use in England, which did not come into line with her neighbours until September 1752. I have followed throughout the Julian calendar still in use in England in 1603, though with some cross-references in the Armada chapters to the Gregorian calendar adopted by Spain in 1582.

Next page