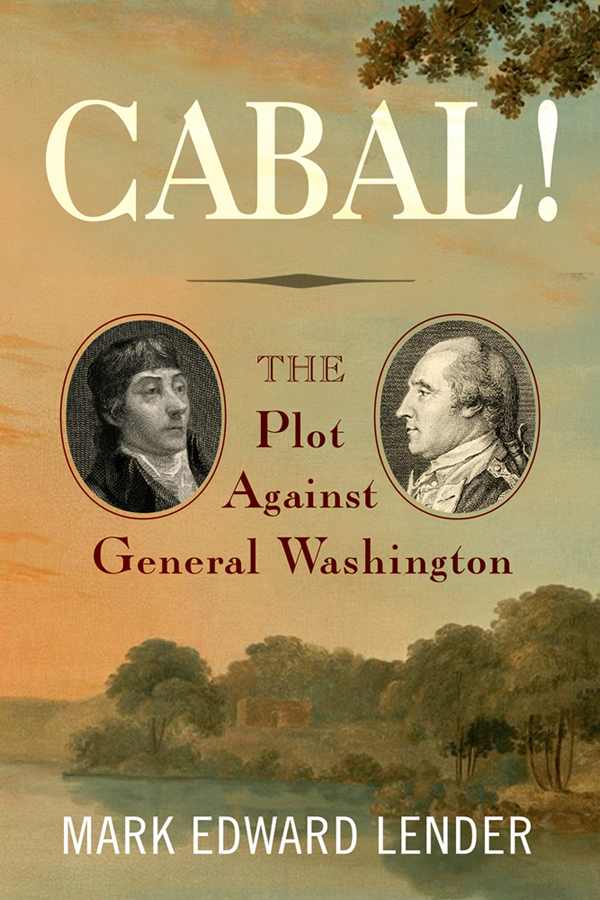

ALSO BY MARK EDWARD LENDER

Citizen Soldier: The Revolutionary War Journal of Joseph Bloomfield, 2nd ed., with James Kirby Martin

Fatal Sunday: George Washington, the Monmouth Campaign, and the Politics of Battle, with Garry Wheeler Stone

The War for American Independence

A Respectable Army: The Military Origins of the Republic, 1763-1783, 3rd ed., with James Kirby Martin

This Honorable Court: The United States District Court for the District of New Jersey, 1789-2000

McCarter & English: A Sesquicentennial History, with Paul A. Stellhorn and Charles Cummings

Middlesex Water Company: A Business History

One State in Arms: A Short Military History of New Jersey

Dictionary of American Temperance Biography: From Temperance Reform to Alcohol Research, the 1600s to the 1980s

Drinking in America: A History, 2nd ed., with James Kirby Martin

2019 Mark Edward Lender

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Westholme Publishing, LLC

904 Edgewood Road

Yardley, Pennsylvania 19067

Visit our Web site at www.westholmepublishing.com

ISBN: 978-1-59416-638-9

Also available in cloth.

Printed in the United States of America.

~For the five guys~

Jace, Kai, Ryder, Von & Nick

PREFACE

LATE MAY 1778 found General George Washington at his Valley Forge headquarters, the brutal winter behind him and his battered Continental regiments healing. He was cautiously watching for the rumored British withdrawal from Philadelphia, and he had the luxury of some precious spare minutes to write an old friend. This was Landon Carter of Richmond County, Virginia, a man Washington had known for decades and with whom he had occasionally exchanged correspondence since the early days of the war. Carter was a man of substance: a wealthy and extensive planter, a major force in Virginia politics and society, a prolific author, and a steadfast supporter of American independence. These were not the sort of things one would write to a casual acquaintance.

And there was something else in the letter, something the general clearly found unsettling but felt he could share with an intimate friend. Washington turned to a matter of which he knew Carter had heard, a matter that had troubled his friend. It concerned a rumored disposition in the Northern Officers to see me superceeded in my Command. While Washington assured Carter he remained secure in his command and that he retained the loyalty of the officer corps, he left no question of his conviction that a plot had existed to remove or discredit him. That there was a scheme of this sort on foot last fall admits of no doubt, he wrote. Washington named no names, but he clearly saw Major General Horatio Gates, the victor at Saratoga in 1777, and Major Generals Thomas Mifflin and Thomas Conway at the heart of a wider intrigue against him. His contempt for all three men was palpable. But he assured his fellow Virginian that all was well, at least for the time being. When their supposed conspiracy came to light, the plotters slunk backdisavowed the measure, & professed themselves my warmest admirers. thus stands the matter at present. He told Carter that as far as he knew he still enjoyed the confidence of Congress, but the implication of the letter was that the matter was not entirely settled.

Washingtons letter to Carter was as candid a statement as the general ever made (that we know about) of his belief in an episode historians have called the Conway Cabal. Had it succeededhad Washington resigned or been relievedthe Revolution easily could have taken a very different course. Like Washington, most historians have pointed chiefly to Gates, Mifflin, and Conwaythe usual suspectsas the individuals most anxious to replace Washington with Gates. In late 1777 and early 1778 Washingtons accumulated defeats in Pennsylvania stood in stark contrast to Gatess success in the North, and there is no question many patriots had grave doubts about Washingtons ability to win the war. But did these doubts actually pose a threat to his command? Many contemporaries thought so, including the commander in chief and his military familyhis inner circle of young aides and other loyal officers. They firmly believed that the threat was real, and over the years they never saw a reason to change their minds.

Most early historians of the Revolution believed the same. Mercy Otis Warren, who published her history of the Revolution in 1805, and who frequently wrote sympathetically of some individuals identified with the Cabal, also believed some members of congress... were intriguing for his [Washingtons] removal. The Franco-Italian writer Carlo Botta, who in 1809 In reading these early histories one sees Washington beset by plotters at almost every turn.

The only notable exception in this early historiography was the historian and Harvard president Jared Sparks. Sparks edited the first published edition of Washingtons writings, and although some of his editorial decisions drew criticism he actually was a fine scholar. However, even with his doubts, Sparks, like the other early historians, saw the Cabal through Washingtons eyes with scant reference to the motives of the generals critics; the perspective was fully one of good guys versus bad guysand Washingtons critics were not the good guys.

So matters stood among most historians until 1941. After a century and a half of writings overwhelmingly complimentary to Washington, much of which was actually hagiography, Bernhard Knollenberg published a rigorously critical reappraisal of Washingtons leadership. Knollenberg, a successful lawyer, was director of the Yale University Library when he wrote his but the prevailing scholarly wisdom generally holds that the Cabal never existed as a serious threat to Washingtons command.

Rather, this post-Knollenberg view of the various events of late 1777 and early 1778 gathered under the name of Cabal were the often understandable concerns, some quite vocal, of Americans frustrated by and worried about the state of the patriot war effort. But such concerns and questions seldom resulted in calls for the relief of the commander in chief, much less an orchestrated stratagem to replace him. Over the almost eight decades since Knollenbergs book appeared the historiography of the so-called Conway Cabal has seemingly reversed itself, the plot replaced by a largely ineffectual, if annoying, gang of carping critics who posed no real danger to the commander in chiefno matter what Washington and his partisans thought.

Yet this dismissal of the Cabal may have gone too far. Critics of the Cabal from Knollenberg on have generally staked their case on the lack of any smoking gun. That is, they have found no documentary record of an orchestrated effort, much less an actual conspiracy, to topple the commander in chief in favor of another officer. But what did they expect to find? Conspirators taking notes? Perhaps minutes of meetings? To reject the Cabal on that basis is unrealistic at best and perhaps even nave. Good conspirators cover their tracks, and even bad ones try. And there are some tantalizing hints that some of Washingtons critics did try. As the Cabal controversy first surfaced Major General Thomas Mifflinfor a time the armys quartermaster general, a Pennsylvania politico, and an astringent critic of the commander in chiefwarned Horatio Gates, Mifflins favored general, to guard his correspondence from prying eyes. After the war, Benjamin Rush, whose These facts, scanty as they are, hardly accord with a no smoking gun theory.