I would like to thank my agent Isabel White, a patient, never-ending source of encouragement, inspiration and expertise, and Hollie Teague, my editor at The Robson Press. Decades too late, I give my thanks to all those squaddies I accompanied under escort back to camp even the one who made a break for it at Leeds railway station for their pragmatic tolerance on their interminable journeys to face retribution.

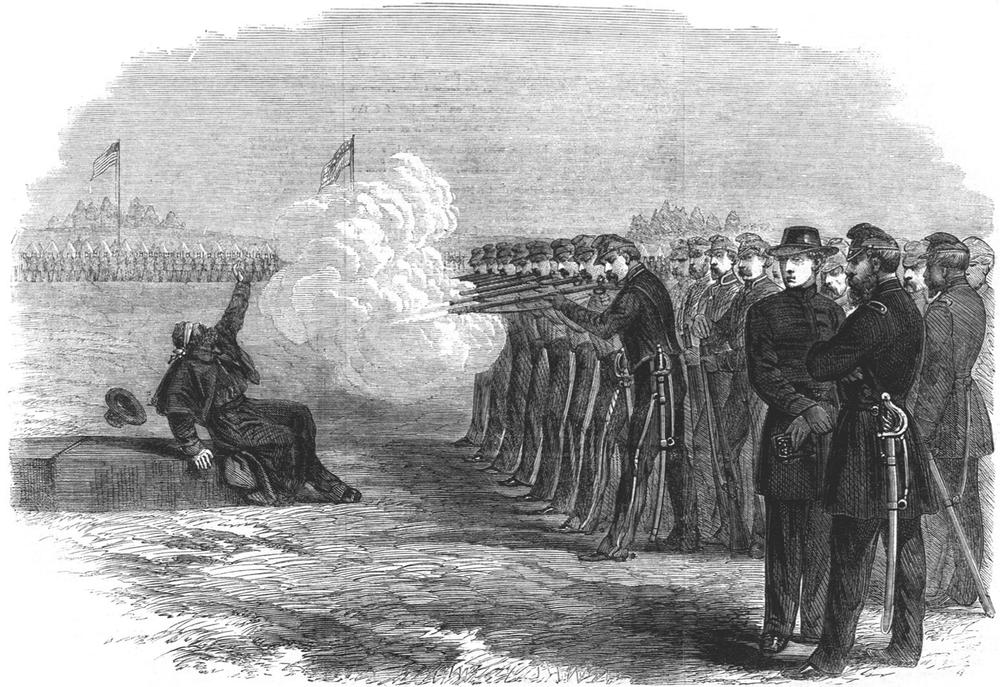

T here have been many books written about valour in battle. This is not one of them. On the Run deals entirely with those men and women who, over thousands of years, have departed with alacrity and for multifarious reasons from life in the armed forces.

As long as there have been military units and organised martial bodies of any kind, there have been men and women who decided that they were out of place in them, did not like serving in them or, for other reasons, chose to walk away from their places of duty.

While deserters have usually been treated by the general public with contempt, sometimes good-natured, sometimes not, this condemnatory view is, tellingly, not always shared by those who have served in the armed forces and appreciate that the line between staying put and fleeing is sometimes a fine one. This was exemplified, not long after the Second World War, in the iconic radio comedy The Goon Show, when its principals, all of them ex-servicemen, could come up with such heartfelt lines as I was in the 4th Armoured Deserters and know that the pusillanimous boast would receive a wryly sympathetic reception from the millions of former soldiers, sailors and airmen listening in.

I first came into professional contact with absentees as an 18-year-old National Service conscript in the early 1950s, when for several months I was detailed to accompany a corporal to pick up recaptured absentee soldiers at police stations around the country and escort them back to their units to face courts martial and possible terms in a glasshouse or military prison. The only solace the sympathetic, cadaverous corporal and I could offer to our charges from the shallows of our experience on these long, often tearful, return train journeys was to urge our distressed prisoners to plead guilty to going absent without leave, implying that all-important intention to return, rather than desertion, as the sentence for the former was much lighter than for the latter. An absconder found guilty of being absent without leave would be sentenced to a period of detention in his units cells. Depending upon the discretion of his commanding officer, this could be roughly for the same length of time as the original length of absence. Offenders found guilty of desertion would be sent to a military correction establishment. A typical sentence here would be from a few months to a year, often followed by dismissal from the service, although much longer penalties could be imposed.

It soon became apparent that many of our absconders were not the rough-hewn, heedless lawbreakers of fiction, but for the most part homesick, contrite and frightened youths. Their inherent gloominess was leavened by the occasional inadequate, slightly older renegade regular soldier who regarded a term in a house of correction as a reasonable, almost inevitable payment for a brief and hectic period of freedom on the loose.

One particularly hardened and incorrigible character of this sort, who had gone on the run and been recaptured on at least half a dozen occasions, had but one complaint. At the time, convicted escapees were liable to be sent to one of the two main military prisons in Great Britain: Colchester or Shepton Mallet. This particular serial absconder had served time alternately at both prisons and regarded the fact with comparative equanimity.

Unfortunately, so our serial deserter would complain to us bitterly on our journeys, each establishment decreed that a different shade of Blanco, the cleaning and colouring compound, should be used for scouring the webbing belts, straps, anklets and packs of their inmates. This meant that, to his enormous chagrin, as soon as he was discharged from Colchester prison he had to spend a great deal of time applying a whole new set of colouring to his equipment if Shepton Mallet were his next destination.

It soon became apparent upon our periods of escort duty where the sympathies of the general public lay. Most men at that time had served in the Second World War or had completed a postwar period of National Service. As soon as some of them caught a telltale glimpse of the handcuffs around our prisoners wrists there would be howls of antipathy directed at his custodians and shouts urging the deserter to make another run for it.

Since those odd days over half a century ago I have sometimes wondered what happened to the callow boys and insouciant old lags who found service life all too much for them and as a result went over the wire. Doubtless upon their discharge the great majority went on to live lives of complete respectability and usefulness, regarding their departed nightmarish period of military service with bewildered amusement.

These thoughts led me to an examination of deserters and desertions in general and in turn to some of the more unusual and interesting absconders down the ages, which has culminated, decades later, in this book. Over the years I have spent much time in many countries reading the transcripts of courts of inquiry and discussing life on the run with one-time deserters and those close to them. These range from a former colonial civil servant who befriended the film star and deserter Errol Flynn in his wild, hedonistic Papua New Guinea days in the 1930s, to a great-grandmother who, in Second World War London, frequently harboured, sometimes simultaneously, her three wayward sons, who deserted regularly from two different branches of the armed forces. This redoubtable lady received so many visits of inquiry from the military police that when she opened the door to her uniformed, red-capped visitors she would merely ask resignedly, Which one do you want?

There have been relatively few books written about the history of desertion. A number of individuals have written or had written for them accounts of their abrupt departures from service life and there have been a handful of books about British deserters in the First World War in particular, in addition to several academic studies of desertion in the American Civil War. Generally, however, any investigations into desertion necessarily have involved at some stage the study of contemporary accounts, regimental records and transcripts, and the files of newspapers.

In these, through the ages, there have been many justifications and pleas in mitigation from those who have abandoned their posts. It is very difficult, however, to establish just why some people desert and others in similar circumstances stay put. In most cases there seem to have been a multiplicity of reasons. The natural desire not to be killed or maimed occurs often; even so, other causes often combine to push the deserter over the edge, or over the wire, in war or peace. Discontentment with military life and boredom feature large, as does homesickness. Personal and domestic problems may weigh heavily, as well as opportunism and bloody-mindedness. Location, climate and weather sometimes influence whether someone remains or goes. Ambition can occasionally impel a desertion, if something better or more lucrative seems to be just over the horizon. Greed was a considerable factor in the days when bonuses were paid to volunteers, causing bounty hunters to skip avariciously from one military paymaster to another. Indifferent and unhelpful officers play their part, as do heavy defeats recently sustained in battle, with subsequent loss of morale leading to defections among the vanquished troops. Coercion by the enemy sometimes provides the deciding factor.