Pagebreaks of the print version

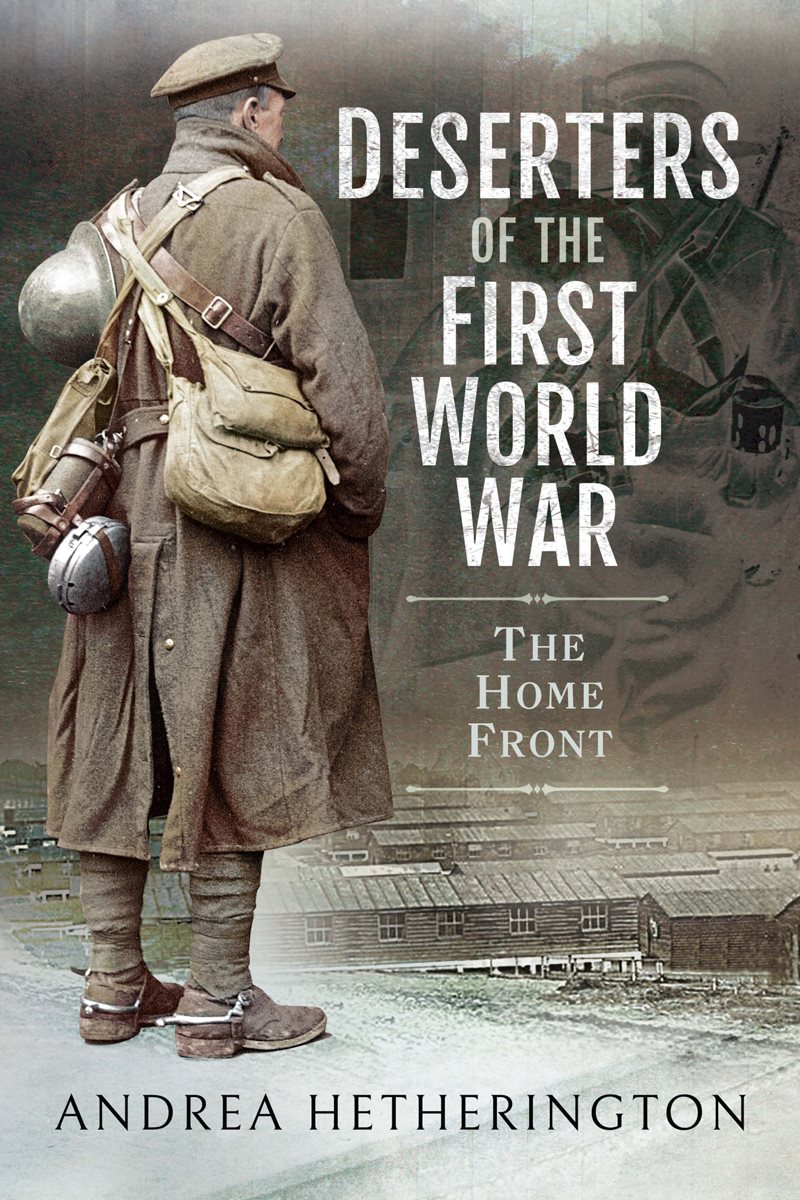

Deserters of the First World War

Deserters of the First World War

The Home Front

ANDREA HETHERINGTON

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire - Philadelphia

Copyright Andrea Hetherington, 2021

ISBN 978 1 52674 799 0

eISBN 978 1 52674 800 3

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52674 801 0

The right of Andrea Hetherington to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers would be glad to hear from them. For legal purposes the Acknowledgements on p. vi and Bibliography on p. 173ff. constitute an extension of the copyright page.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and White Owl

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LTD

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Acknowledgements

There are many people to thank for their part in ensuring this book made it to publication. The manuscript was a year late, so my first thanks are due to Rupert Harding, Alison Flowers and all at Pen & Sword for their infinite patience and understanding.

I feel very lucky to have been able to take advantage of the comradeship and expertise of scholars at the University of Leeds, especially Anne Buckley, Alison Fell, Jessica Meyer, Ingrid Sharp and Claudia Sternberg. Along with Lucy Moore of the Leeds Museums Service, they have been incredibly supportive over the last few difficult years in particular and I am eternally grateful to them all. Beyond Leeds, Rachel Duffett has been a wonderfully encouraging voice during the lonely writing phase of the project.

Thanks must go to those who, sometimes unknowingly, through conversations, suggestions, questions and comments have informed the structure and content of the book. Susan Grayzel, Toby Haggith, Edward Madigan, Cyril Pearce, Tom Thorpe and Richard van Emden all gave me faith that this was a book worth writing.

Thanks, as usual, are due to the library and archive staff who have made research a joy. Leeds Central Library, The National Archives, the British Library at Boston Spa and Special Collections at the University of Leeds have treasures behind the desk as well as on the shelves.

I want to thank everyone who has given me practical support, from my family who were willing to drop everything for me when required, to friends who have given me lifts and lifted my spirits. Linda Gilhespy showed even more patience than usual and deserves a medal.

Finally, I must thank Dr Nicola Bell and Mr Kenan Deniz for their care and skill. Without their combined talents I would not be in a position to write this book or any others.

Plates

Recruits training in 1914.

Postcard from camp.

Front page of the Police Gazette supplement of 2 May 1916.

Gus Platts, the Sheffield boxer.

Taken 3 days leave/Got 6 days C.B.

Deserter or absent tea?

Conscription for me? Not likely!

Leonard Ewart Nixons gravestone at Lawnswood Cemetery in Leeds.

Depiction of a medical examination at a recruiting office.

John Bull mocking the ease with which Farmers Boys escaped conscription.

A patriotic postcard produced by Fred Spurgin.

Cowling, the Deserters Village.

Canadian camp on Salisbury Plain.

The Canadians meet for Sunday prayers. The soldier sending the cards back to Canada addressed this one to his mother

The soldier sending the cards back to Canada addressed this one to his father

An advertisement for The Beaver Hut, a magnet for Canadian soldiers and those interested in meeting them.

The Cippenham War Memorial.

Frank Lennard Walters, at Bray in France with 52nd Battery Royal Field Artillery.

Introduction

The centenary period saw an explosion of works on many hitherto neglected topics yet the history of deserters from the British and Dominion forces remains largely unexamined. A number of books have been published about the men who were executed by the British Army for offences which may have included desertion, but the concentration on this very small number of men obscures the reality that there were many thousands of individuals who defaulted on their military obligations. Most deserters did not walk away from trenches in France and Belgium but strolled out of military camps in Britain or did not return from leave.

Most deserters were not shot at dawn but were given periods of detention of varying lengths. Unlike the British soldiers executed by their own comrades during the war, no one has campaigned for these deserters and absentees to be pardoned and their stories have remained largely hidden. Disapproval after the war meant that they were not keen to publicize their misdemeanours as they faced enough of a struggle to re-establish themselves within the civilian community without identifying themselves as deserters. The story of these men has remained untold.

Between 4 August 1914 and 31 March 1920 the official end of the war, there were 141,115 courts martial held in respect of officers and men from the British and Dominion forces at home, with 82,423 of these being prosecutions for desertion and absence without leave. Persistent deserters were often sent across the Channel during the war, desertion on the front line being more difficult and dangerous than at home.

These figures considerably underestimate the numbers who did absent themselves during this period, as not every offender would have been caught and not every arrestee would have been court-martialled. Many were punished The names of deserters and absentees, along with their descriptions and other information taken from their enlistment forms, appeared in the Police Gazette every week to hasten their arrest. The 11 August 1914 edition contained eighty-one names from the Regular and Territorial armies, all of whom had gone missing from the army in July and the first three days of August 1914. The edition of the circular printed on 26 January 1915 listed 918 deserters, a massive increase in less than 6 months. Names continued to appear at a rate of around 1,000 a week during the war years, whilst the equivalent list of men who had returned or were no longer sought rarely ran to more than 100 per edition.

The official statistics show that the loss to the British Army alone from desertion during the war was 114,670 men up to January 1919, though it was claimed that many of them had re-joined the services. Though they may have re-joined, there were always others ready to walk away and the net loss to the British and Dominion forces from desertion up to the same date was 70,189. Another 20,000 men would absent themselves during 1919. Had this number been killed in a particular action it would take its place in the pantheon of notorious battles alongside the Somme and Passchendaele: as it is, the huge number of deserters and absentees are barely spoken of at all. The truth is that desertion and absence were an everyday part of army life and of the experience of many thousands of British and Dominion soldiers.