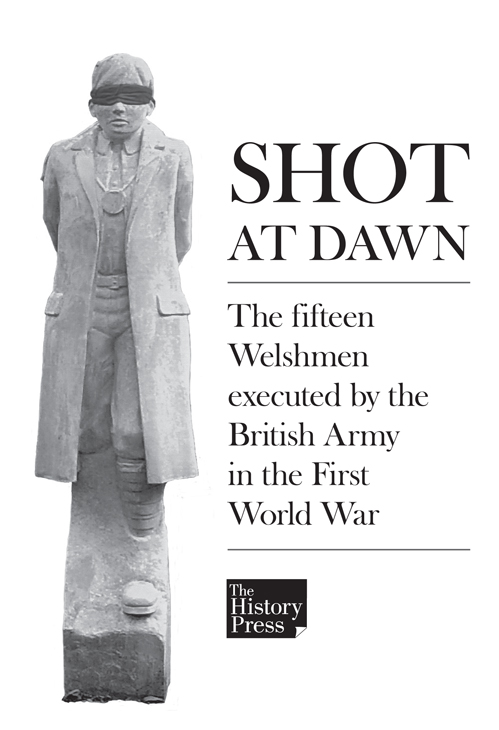

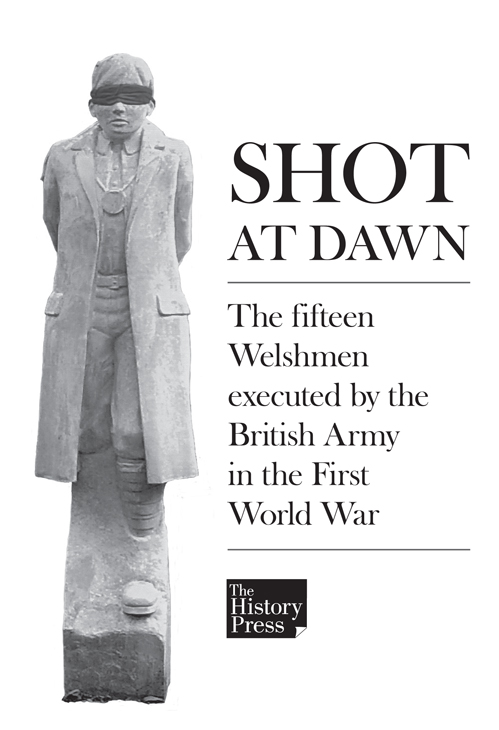

This book is dedicated to John Hipkin, who campaigned resolutely for a blanket pardon to be granted to the 306 soldiers who were shot at dawn by the authority of the Army Act during the Great War; and to the late Ernest Thurtle MP, whose resolve never swayed in his aim to achieve some degree of justice for them; to Andrew Mackinlay; and to the Right Hon. Des Browne, who brought the campaign to fruition.

I am indebted to the following for helping in the making of this book: Darren Nichols, who has driven me hundreds of miles during the research; the Right Hon. Peter Hain MP, who has kindly written the foreword; Glyn Davies; Martin King; Richard Dyer; Brian Lee; Brian Baker; Lolita McAllister; Derek Vaughan MEP; Dr Paul Davies; Gareth Mathias; Barrie Flint, for drawing the maps; Daniel Smith; the Royal British Legion; the National Memorial Arboretum; Public Record Office; the Imperial War Museum; Leeds University; the Whitehall Library; Ministry of Defence; Declan Flynn and Naomi Reynolds of The History Press; and to my wife, Joy, for all her support.

Contents

When Robert King asked me in 2006 to support a proposal in the House of Commons to grant a blanket pardon to those soldiers who were shot at dawn in the Great War, I was pleased to do so.

The terrible injustice suffered by 306 British men executed under the Army Act has been like a deep festering sore. Their offence was quite likely to be suffering from shell shock now called post-traumatic stress syndrome. Through no fault of their own they downed arms and could not serve, so breaching the regulations stipulated by the Army Act. The Shot at Dawn Campaign struggled for years to get recognition and pardons, which were finally granted by the government in which I served in 2006. They were victims of war rather than failures at war.

In the years following the First World War, their cause was raised with great passion in the House: the Labour MP Ernest Thurtle being one of the first to do so, in the early 1920s. He argued that the executed soldiers should be laid to rest in graves alongside those men who fell in action, after responding to a petition submitted by a soldier who felt that they should be honoured in the same way.

Thurtle was successful, and the men who died whilst facing the firing squad were laid to rest with the millions in the impeccably kept cemeteries in Belgium and Northern France.

After Thurtles time in Parliament, a pardon was raised on a number of occasions until it was finally achieved. But Robert King is not judgmental about the army. The Great War was a bloody, vicious conflict arguably the worst in history for the sheer scale of casualties: men almost wantonly thrown into action and to their deaths, forced to run over the top to a fusillade of fire and shells amidst the mud and the hideous, pounding chaos. Everyone was under unspeakable pressure as all hell broke loose and they witnessed the carnage, the ugly haunting stench of death everywhere. The officers at the time were adhering to the rules and regulations of the Army Act. Only a shade more than 10 per cent were shot, the rest suffering lesser punishments, though still with the stain of being cowards on their record.

The fact that many of the trial papers were destroyed after the Second World War was used as an excuse for why the subject should not be taken further.

But the Shot at Dawn Campaign persisted nevertheless. The Royal British Legion favoured a blanket pardon with the exception of those soldiers who had been executed for murder. And when it was brought to my attention that a man from my own constituency of Neath had faced the firing squad, my interest was intensified.

Many had no prisoners friend in support and were not eloquent enough to defend themselves: many were shot as an example to others.

It is important that their stories are told and that their names should be added to the war memorials up and down the country. In very recent times, members of the Campaign have been allowed to march in the parade through London on Armistice Day. I urge anyone who has not visited the National Memorial Arboretum in Litchfield, Staffordshire, to do so and see the Shot at Dawn Memorial and take note of the very young ages of those men who seem to have cracked under the fearsome pressure and were executed for it.

Robert is to be commended for focusing upon the Welsh soldiers whose stories have not been told and whose memory we salute through this book.

The Rt Hon. Peter Hain

MP for Neath, former Secretary of State for Wales

Ynysygerwn, Neath

January 2014

My interest in the plight of those unfortunate men who suffered the fate, under the authority of Army Act, of being shot at dawn during the Great War, was ignited when I reviewed the Julian Putkowski/Julian Sykes book, Shot at Dawn , in 1989. Absolute ignorance had prevailed in my knowledge in respect of punishments doled out to those who transgressed against the British Armys rules before I was sent the book by its publisher, Leo Cooper. I was familiar with the phrase shot at dawn it was used often by people in authority, particularly in the early years of the 1960s (by authority I mean those who were training and educating young people in that decade). I worked then in the horse-racing industry in Herefordshire and my employer was Peter Ransom who would, when I failed to muck out stables efficiently or fell off a horse, issue the threat: Youll be shot at dawn. The real meaning passed me by with the process of growing up, but thirty years on it took on a dark shroud: the phrase has haunted the families of the men who were marched out of a building on the Western Front just as dawn was breaking across the French or Belgium landscapes. They were to be faced with a firing squad, usually consisting of men from the unfortunates own battalion, literally blindfolded and alone often having been convicted with no mitigation submitted.

I admit I became incensed with what I considered to be an injustice and started to write letters to support the loosely aligned campaign started by John Hipkin, hearing about and understanding the immense amount of work carried out in Parliament and beyond over many, many years by the Labour MPs Ernest Thurtle and Andrew Mackinlay, to secure a blanket pardon for the 306 British and allied soldiers who had been executed.

Then my attention focused on those Welshmen who had been regulars, volunteers or conscripts and then faced a firing squad for committing one of the variety of offences, when, either through in some cases alcoholic inebriation or shell shock (now called post-traumatic stress syndrome). There were fifteen of them: four were convicted of murder, ten for desertion and one for leaving his post. Those men had not been specifically documented in a Welsh context: details of those from England, Scotland, Ireland and other allied countries had been considered, those from Welsh Regiments had not.

It can be very difficult to identify soldiers who served with different regiments often across the English/Welsh divide. George Povey, for instance, was from Flintshire in Wales but served in the Cheshire Regiment, and a number of Englishmen fought with Welsh regiments. This crossover has been researched as thoroughly as possible but at times it has proved impossible to identify where soldiers originally came from and some may have been missed.

Other documents generally say that of the 306 men, fifteen were Welsh and my research supports those findings.

Next page