D IAGNOSING D ISSENT

Hysterics, Deserters, and Conscientious Objectors in Germany during World War One

R EBECCA A YAKO B ENNETTE

C ORNELL U NIVERSITY P RESS

I THACA AND L ONDON

For Ella

C ONTENTS

A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

I owe my appreciation to many people and institutions that helped make the completion of this book possible. First, I would like to thank the staff at the several archives I visited to undertake my research. They not only helped me find sources vital to my research but also made going to the archives an enjoyable experience. The knowledge and kindness of so many people at the archives I visited have contributed greatly to this book.

I received funding for my research both from the Gerda Henkel Stiftung and from Middlebury College. The generous support of these institutions allowed me to make multiple research trips for this book and devote significant time to its writing.

I also owe gratitude to several individuals who helped me think about the ideas I wanted this book to express, offered advice, found archival sources, attended conference talks, and read drafts. Their suggestions made this book better; their encouragement helped me to keep going. In particular, I would like to thank Paul Lerner, Gundula Gahlen, Joachim Radkau, Bernd Ulrich, Philipp Rauh, Bjrn Hofmeister, Wolfgang Schaffer, Maike Rotzoll, Regina Keyler, Erhard Knauer, Susan Burch, Paul Monod, Febe Armanios, Susan Ferber, Jonathan Sperber, David Blackbourn, Helmut Walser Smith, Michael Gross, Martina Cucchiara, Maria Mitchell, Michael OSullivan, Mark Ruff, Aeleah Soine, and Lisa Zwicker. I am also grateful to the anonymous readers who shared their time and expertise.

Emily Andrew has been a tremendous editor whose guidance has helped shepherd this project smoothly through the publication process. I have enjoyed working with her and with Cornell University Press.

Finally, I would like to express gratitude to my family. Momo, Lena, and Siggimy four-legged companionssat up with me even when I worked late into the night. My husband (and best friend) James Fitzsimmons heard more about this project than anyone else. He has likely memorized certain passages after reading so many drafts. My daughter Ella was a good sport, even as a toddler, despite this book seriously eating into playtime. I will never forget how she reacted one day when my husband and I told her something great had happened. She responded by asking if I had finished my book. (Actually, she had won a local coloring contest for four-year-olds!) I could not have written this book without my familys support and patience. I owe them the deepest gratitude.

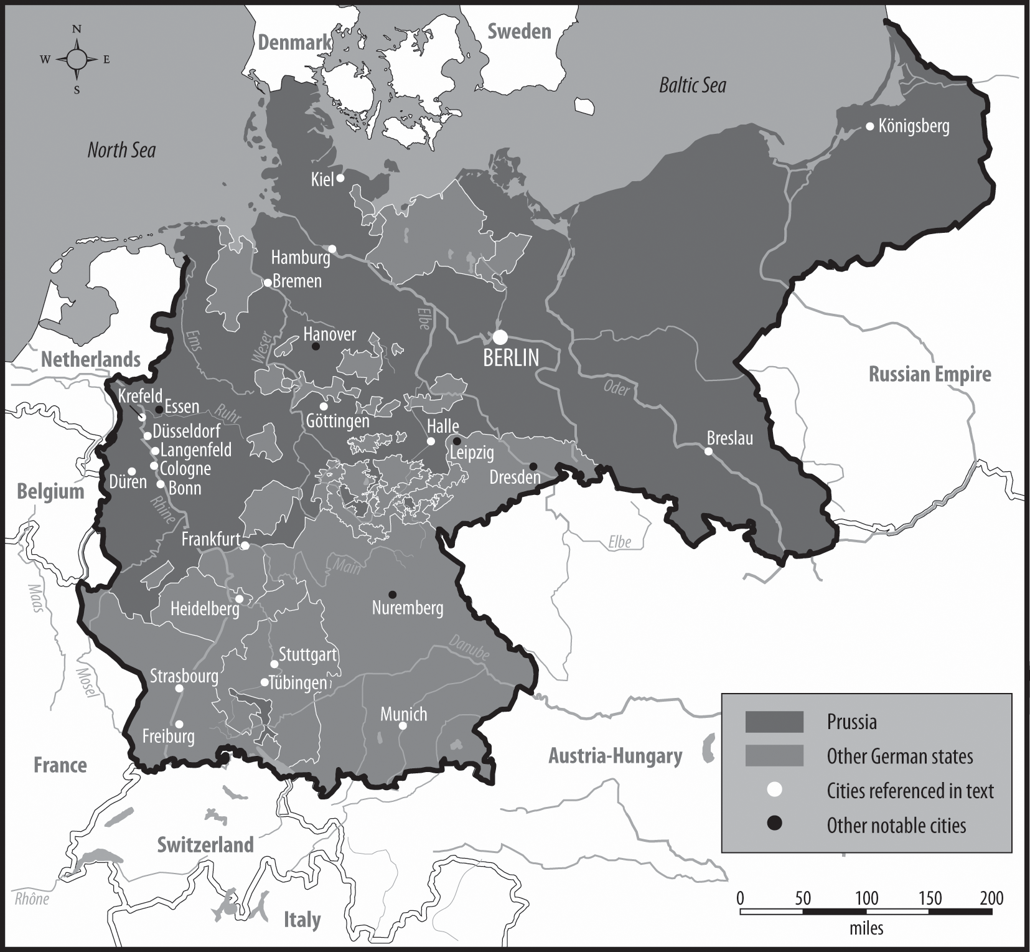

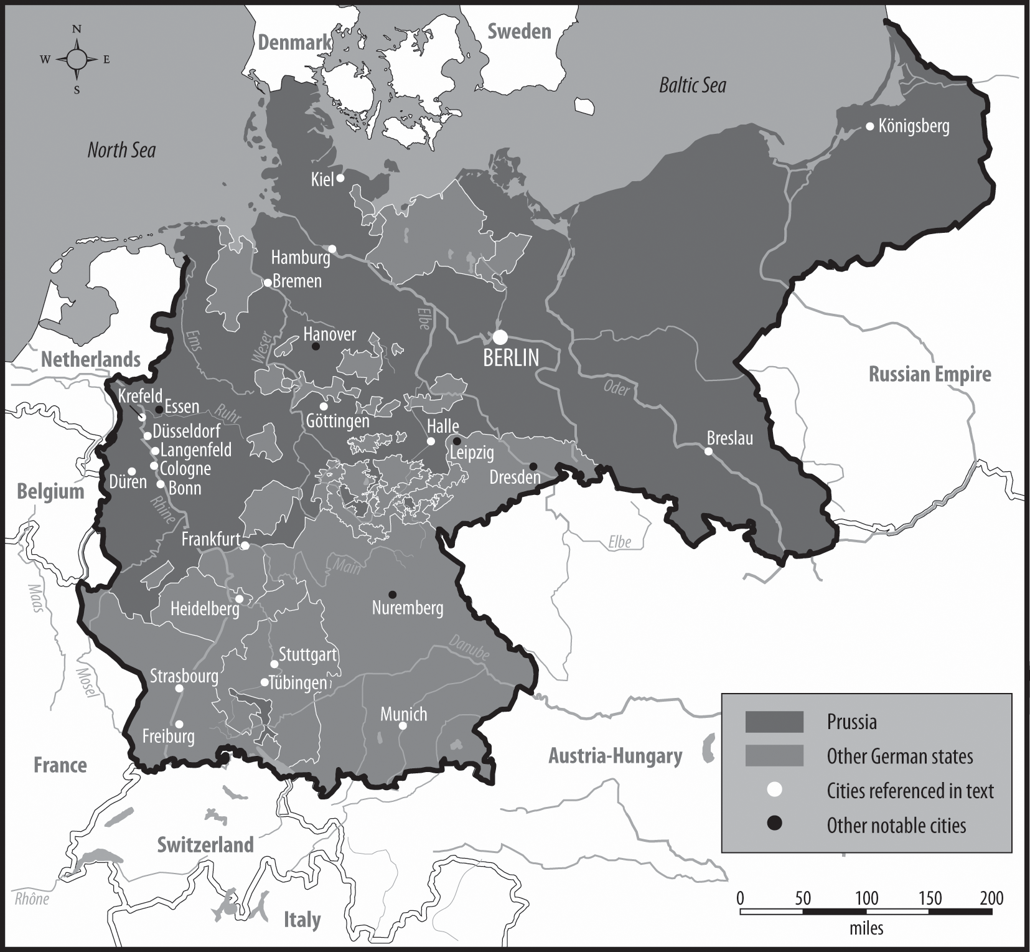

Map of Germany, 1918, by Mike Bechthold

I NTRODUCTION

On July 14, 1917, a twenty-four-year-old soldier named Wilhelm W. arrived in Dren at the psychiatric hospital for observation of his mental state. Writing home to his sister just days before his hospitalization, Wilhelm W. lamented, You cannot believe how I have suffered in this war. I have come close to insanity. This time has made an indelible mark on me. No doubt he had been through a lot by this point. World War I had been raging for the past three years across Europe, and Wilhelm W. had been a soldier for much of that time, serving first on the eastern front in Russia and then in the west in France. The stress and dangers of combat likely struck him as quite alien to his life before the war; he was a painter of figures by occupation. Indeed, responding to the intake questions about events leading up to his transfer under military order to the hospital, Wilhelm W. again acknowledged the strain he had been under: I felt that I was going crazy.

Multitudes of German soldiers likely uttered similar words in military and civilian hospitals across the battlefields and at home. Indeed, the stresses of cataclysmic, long-standing war had created hundreds of thousands of psychiatric cases for the military to deal with by 1917. All told, the official statistics record was over six hundred thousand cases by the time the fighting ended.

One can see from the file the details that led the hospital staff to diagnose dementia paranoides. By all accounts Wilhelm W. was withdrawn and insisted he wanted nothing further to do with other people. He even answered a question about whether he had any enemies with a resounding Oh, yes! People to whom one is disagreeable. But I dont have anything to do with that anymore; the names of all souls that were in my company have escaped my mind. That he claimed to no longer recall the names of any of his former troop members could not have been a reassuring sign of health to the hospital staff either. No doubt the diagnosis also took into account Wilhelm W.s behavior even before he arrived for observation. After all, it was seemingly peculiar behavior that had triggered the psychological evaluation to begin with. Insofar as the hospital staff was informed, this included having to repeatedly be brought back to his post, refusing to follow orders, and believing that a recently arrived corporal was trying to manipulate and control him. The aforementioned letter the soldier wrote to his sistera copy of which was included in the file for doctors to consultserved as further evidence of mental illness: Wilhelm repeatedly referenced the need for secrecy, noting that he could not reveal the real reasons for his actions to anyone there. He did not even dare write them in the letter.

Certainly, all these details from before and after his arrival at the hospital, both reported by others and declared by the patient himself, indicate a man in the midst of a crisis. Yet, a closer look at Wilhelm W.s file suggests the young soldier may have been in the midst of a far different internal struggle than one involving an unfolding episode of schizophrenia. When confronted with leaving his post on two separate occasions in June, Wilhelm W. did discuss the treatment he received from the corporal who thought he could do whatever with me that he wanted to. At the same time, however, he also pointed out that his reason for leaving and refusing to follow orders was that he was fed up with the war. Indeed, the second time he left was no random moment but right after he was told to join other units in positioning mines, an order that was issued three times but did not change Wilhelm W.s refusal. Furthermore, the event that appears to have been the final straw in the commanders patience with his intransigencein other words, the act that precipitated Wilhelm W.s arrest and transfer to Dren for an evaluation of his mental statewas yet another refusal, this time to position artillery shells for use.

Even Wilhelm W.s claims of persecution by the corporal and the existence of enemies among his company members can be understood in quite a different light than signs of paranoia when other evidence from the patient file is weighed. Complaints about poor treatment from superior officers and fellow soldiers hardly stood out in accounts of soldiers and were difficult to assess for their validity. Yet, that the relationship between Wilhelm W. and these other members of his company was bad is quite believable when one considers his multiple refusals to follow orders and share in the workload. As both physicians and patients in many other cases attested, soldiers considered shirkers were often harshly treated by other troops, who felt they had to make up the work. The repeated questioning of orders did not likely endear Wilhelm W. to the corporal either, a point confirmed by their last reported interaction. According to testimony by the patient after his arrest, the final incident began with the corporal asking (not ordering) Wilhelm W. if he wanted to help position shells. Upon Wilhelm W.s answer in the negativeindeed, he went further by adding that he would rather be shot dead before he went to position themthe corporal then issued the formal order for him to do so.