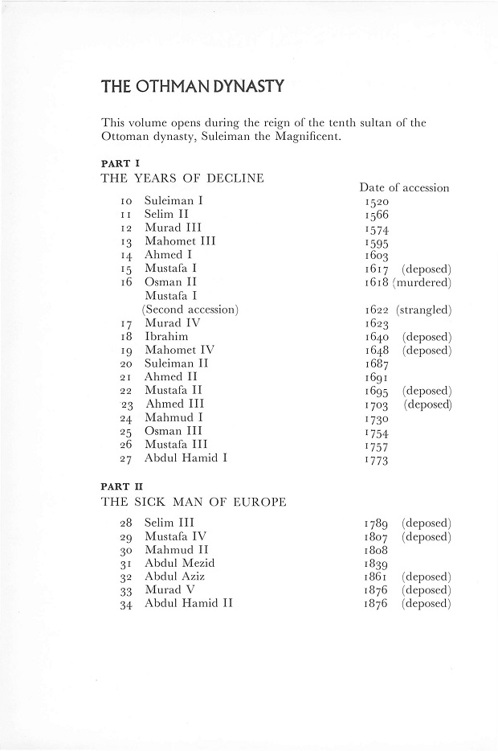

THE OTHMAN DYNASTY

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

LIST OF MAPS

Part 1

THE YEARS OF DECLINE

Chapter 1

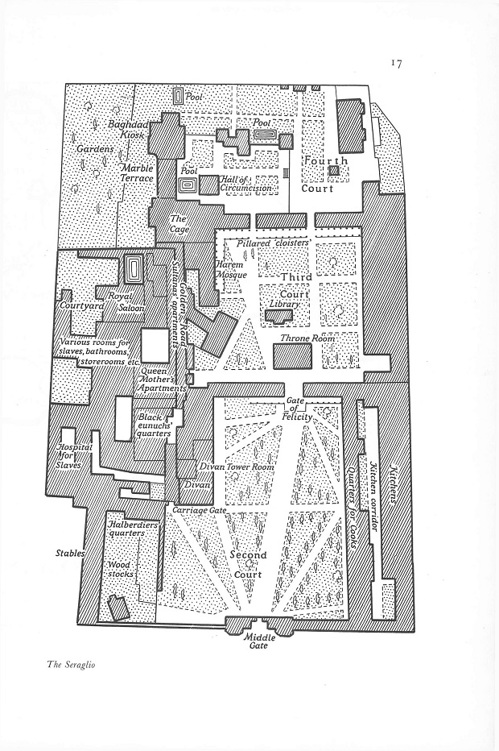

THE GRAND SERAGLIO

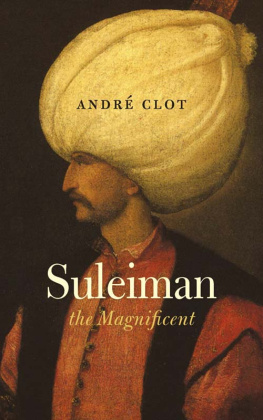

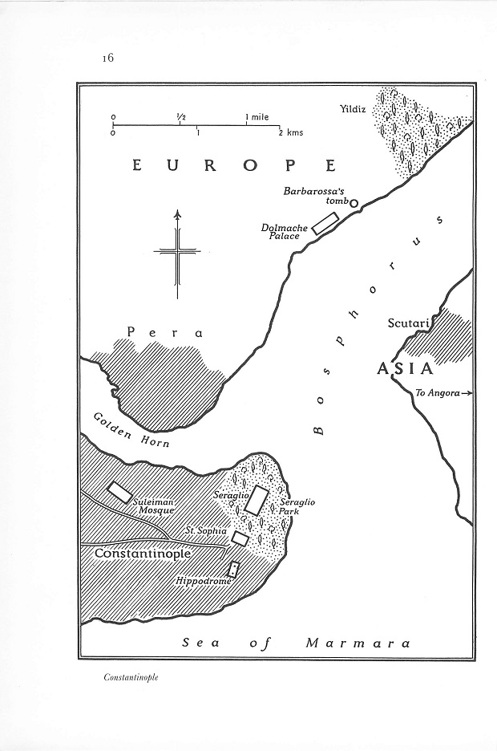

In those last days of untarnished glory in the mid-sixteenth century, when the Ottoman Empire extended from the gates of Vienna to the Yemen and Aden, from Persia to Oran, when the Sultan Suleiman ruled over six of the seven wonders in the world, there was no place more magnificent in its oriental splendour than the private world that lay behind the arch of the Imperial Gate in Constantinople - the Grand Seraglio of the Sultan. The sea walls of this impregnable fortress were lapped by the Sea of Marmora and the Golden Horn. It was a town of 5000 people within a city; its heart beyond the inner Gate of Felicity beat in the harem with its hundreds of odalisques and slave girls zealously guarded by pot-bellied or wrinkled black eunuchs.

Constantinople itself was the worlds most beautiful city. Standing on seven hills, wrapped in the Bosporus, the Sea of Marmora and the Golden Horn, water was as much a part of the city as the gently sloping forests of cypress or the bustling suburb of Pera with its tiled-roofed houses across the Horn. It was cosmopolitan too. The Patriarch of the Orthodox Church prayed almost within earshot of the stables where Sultan Suleiman kept his 4000 horses; in the great covered market Jews and Moors, most of them refugees from the Spain of Ferdinand and Isabella, worked side by side. Behind the market the Serbs lived in the quarter they had nostalgically named Belgrade. Berbers and Arabs from Africa and the Red Sea toiled in the warehouses lining the shore, protecting the spices, ivory, silk and pearls imported by their masters. It was a city of many peoples and by the violent standards of the Empire it was a city at peace. Perhaps the beauty of the ever-present waters, alive with skimming caiques, helped. Perhaps the monuments to bygone Byzantium that still remained - the Hippodrome, the Church of St Irene, St Sophia helped too. The narrow streets of Constantinople might have been made of clay, the new houses of flimsy wood ready to crackle at the first touch of fire, but the streets hummed with the life of citizens whose skins varied in colour as much as their gaudy clothes, but who might have been 10,000 miles away from the vast parks and villas of the Grand Seraglio which lay in their midst on a tongue of land, a hillside gently sloping to the sea which three-parts girded it, with the green shores of Asia ahead and the trees behind.

This was a hidden world of golden domes and pointed minarets reaching for the sky like manicured fingers; of dark cypress groves hiding kiosks, or villas, their walls of marble, glittering mosaics or exquisite tiles; of artificial lakes and pleasure gardens, of the mingled scents of herbs and fruit trees and roses, of an imperative silence broken only by the tinkling of scores of fountains. In the latter half of the sixteenth century, when the Ottoman Empire was at its zenith, poised at the very moment in history before its triumph was flawed, no court in Europe was its equal, even though Europe was enjoying a golden age dominated by the spirit of the Renaissance: Visili Ivanovitch, the Grand Prince of Moscow, was laying the foundations of Russias greatness; Pope Leo X was turning Rome into an intellectual garden; Henry VIII ruled England, Charles V Spain, Francois I France, and, further south, Gritti, the Doge of Venice, the one city above all others that was the gateway to the Levant. Barely thirty years had passed since Columbus stepped onto the shores of a new world.

Europe was coming of age, having built up its first naval squadrons, its first permanent armies, and having discovered the principles and use of artillery. Yet Suleiman was superior to all the European powers in battle, while at home he was, with his architect Sinan, building mosques, schools and hospitals which rivalled the works of the master builders of Europe; Michelangelo was at this time struggling to raise the dome of St Peters and Francois I had started to rebuild the Louvre. Despite the thirteen wars in which he personally led his soldiers into battle, Suleiman had time to produce an improved code of justice - and incidentally to execute corrupt officials (including one son-in-law) for acts of injustice. He husbanded his vast treasures; his standing army of 50,000 was well paid. He had a literary bent, was a disciple of Aristotle (and his hero was Alexander the Great); he kept a daily diary when at war, he wrote poetry when at peace.

The Venetian envoy to Constantinople at the time described him as a man of commanding personality, tall, thin, with a prominent brow, startling black eyes and an aquiline nose above long moustaches and a forked beard, which partly softened the thin mouth with its trace of hereditary cruelty. His complexion, he said, was as if smoked. He was relentless and proud, and a stickler for protocol, particularly for the Friday prayers when the streets were lined with people.

Friday was, of course, the Moslem Sabbath, when Suleiman usually prepared to go to prayer in St Sophia. The Master of the Wardrobe had laid out all his clothes, scenting them with aloes. Suleiman wore a gown of heavy silk and over it a sleeveless robe trimmed with ermine. On his head he wore a wide oval turban with an aigrette of peacock feathers held in place by a clasp of diamonds. His white horse was ready, its heavy leather saddle studded with precious gems.

Outside in the first court of the Grand Seraglio, ringed by a wall three miles long, a cast of characters drawn from the Arabian Nights awaited the moment when their lord and master would emerge and ride along its paved paths past the higgledy-piggledy workaday buildings needed to sustain a town of 5000 people a bakery on the right, a giant wood-store on the left, big enough to hold 500 shiploads, and guarded by the Tressed Halberdiers whose headgear incorporated wigs on either side of their faces in case they tried to steal a glance at the Sultans odalisques when carrying wood for the harem fires.