Copyright 2021 by Marc David Baer

Cover design by Shreya Gupta

Cover image Worcester Art Museum / Jerome Wheelock Fund / Bridgeman Images

Cover copyright 2021 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

First Edition: October 2021

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

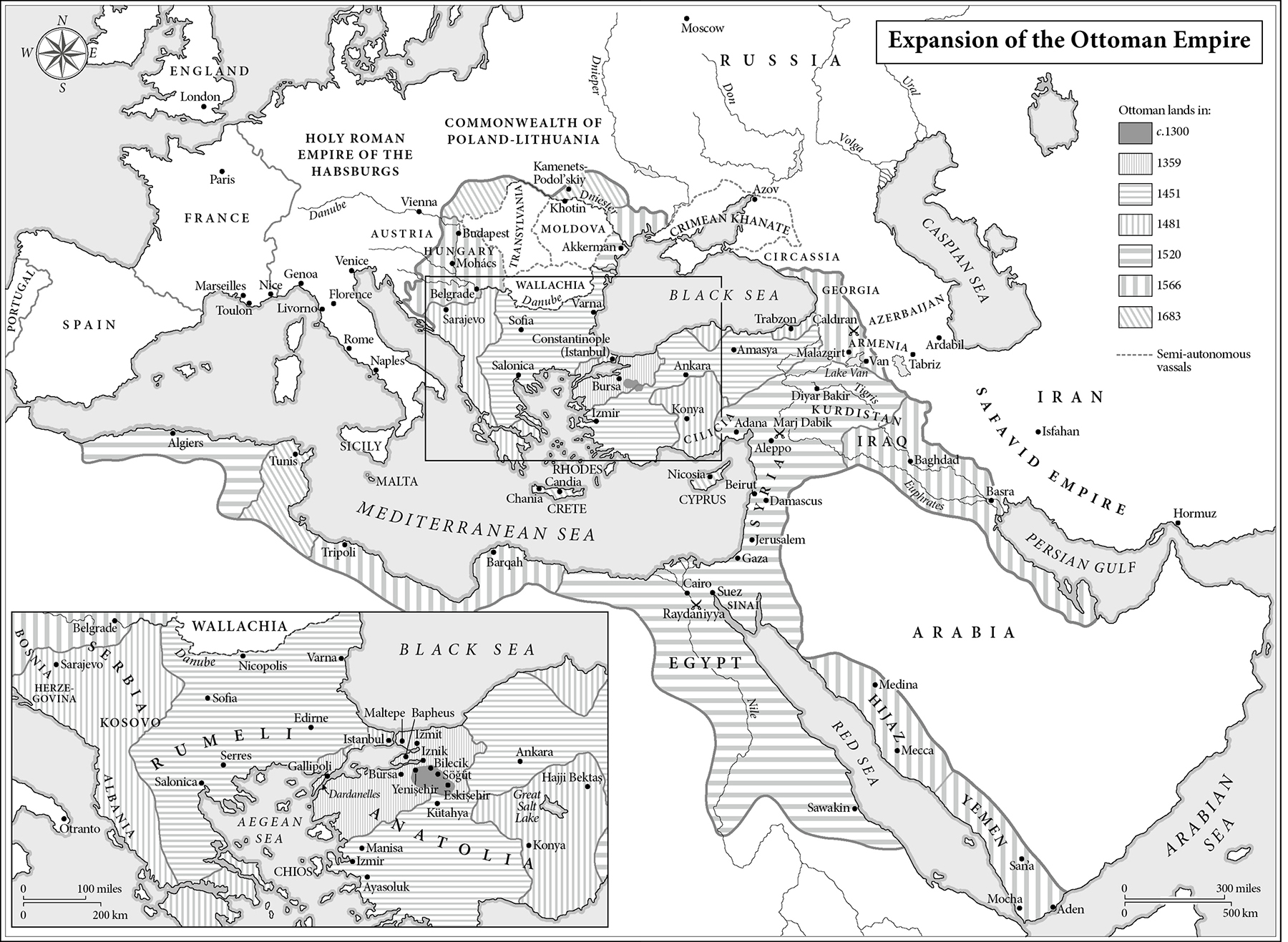

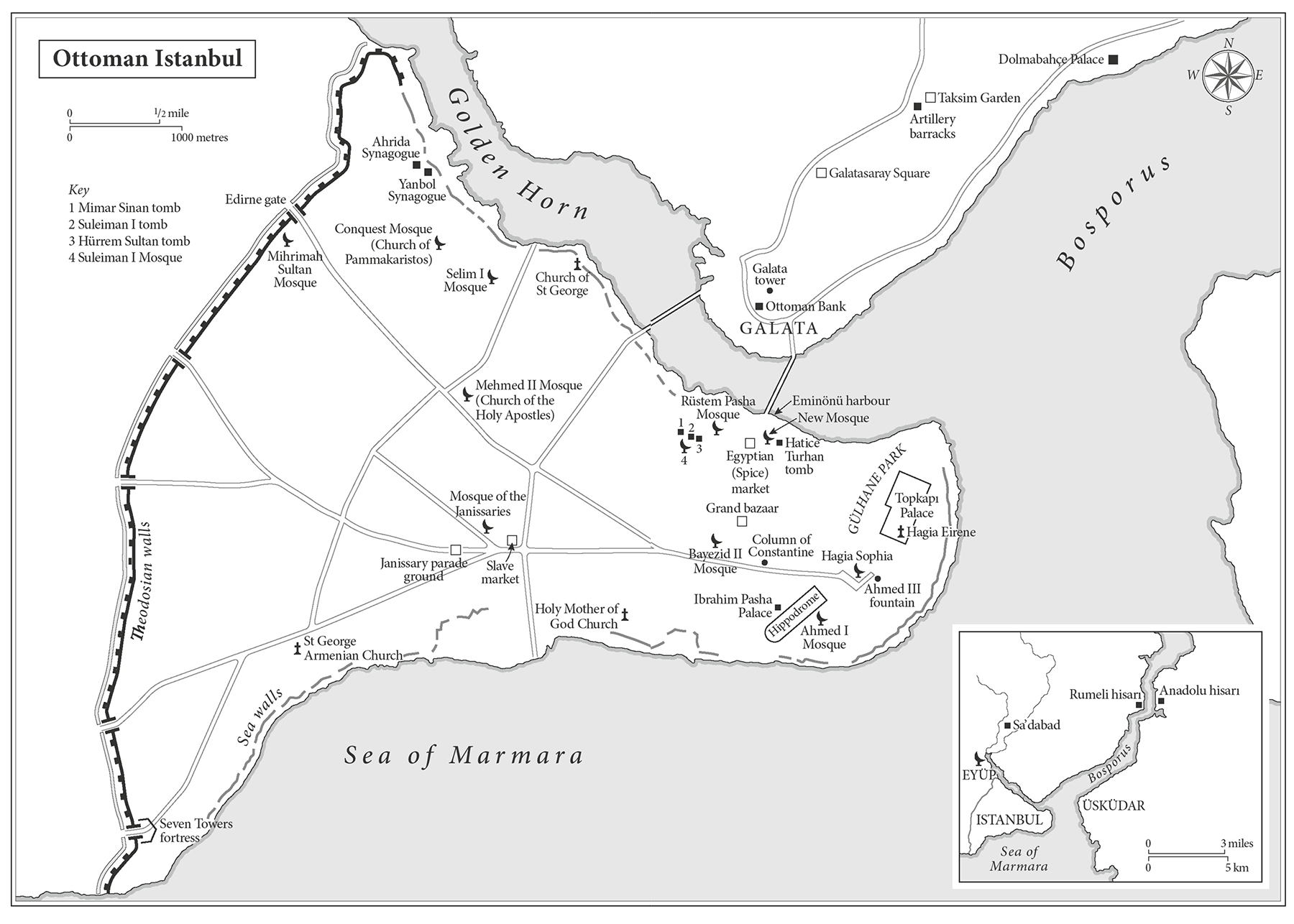

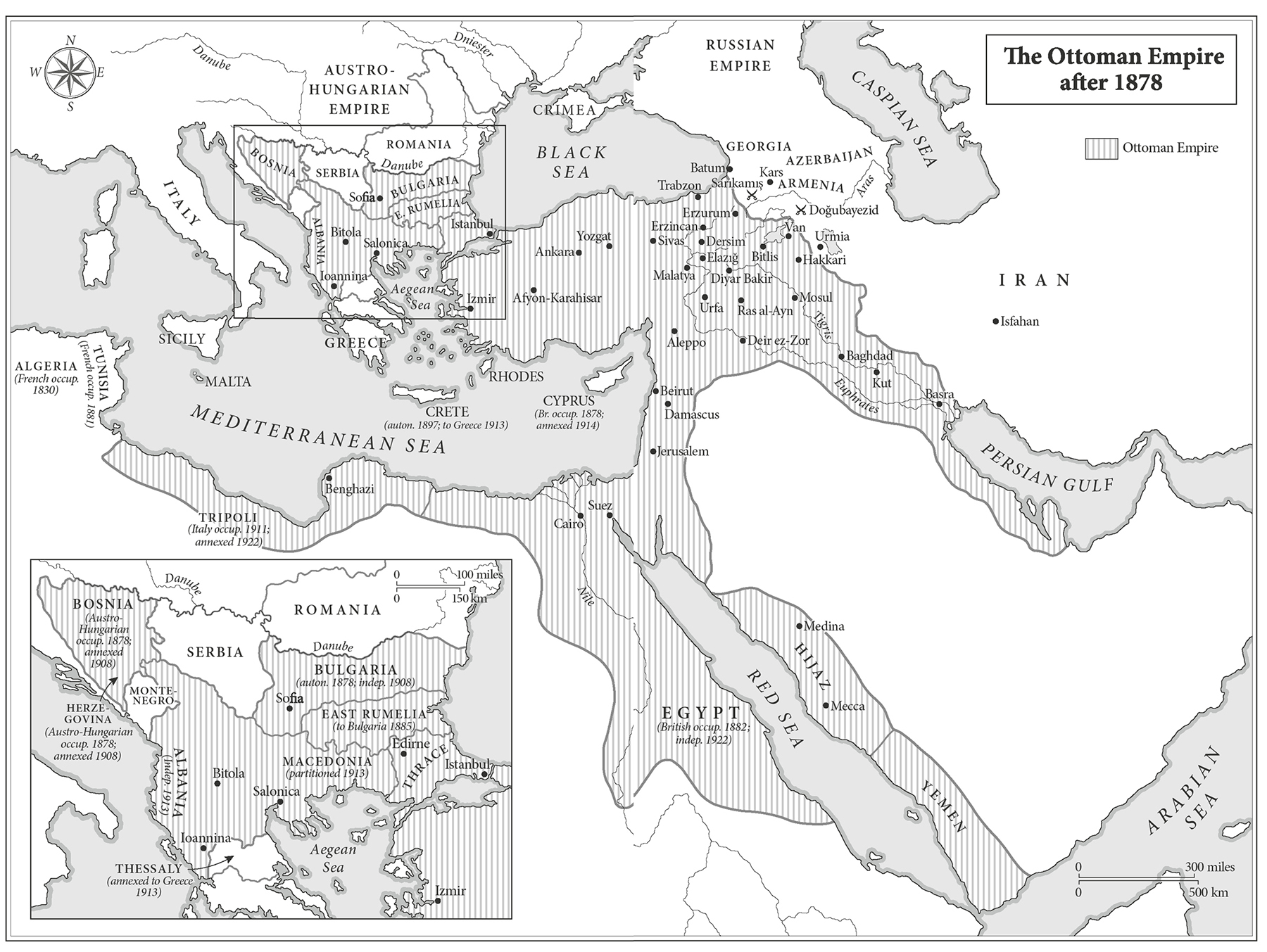

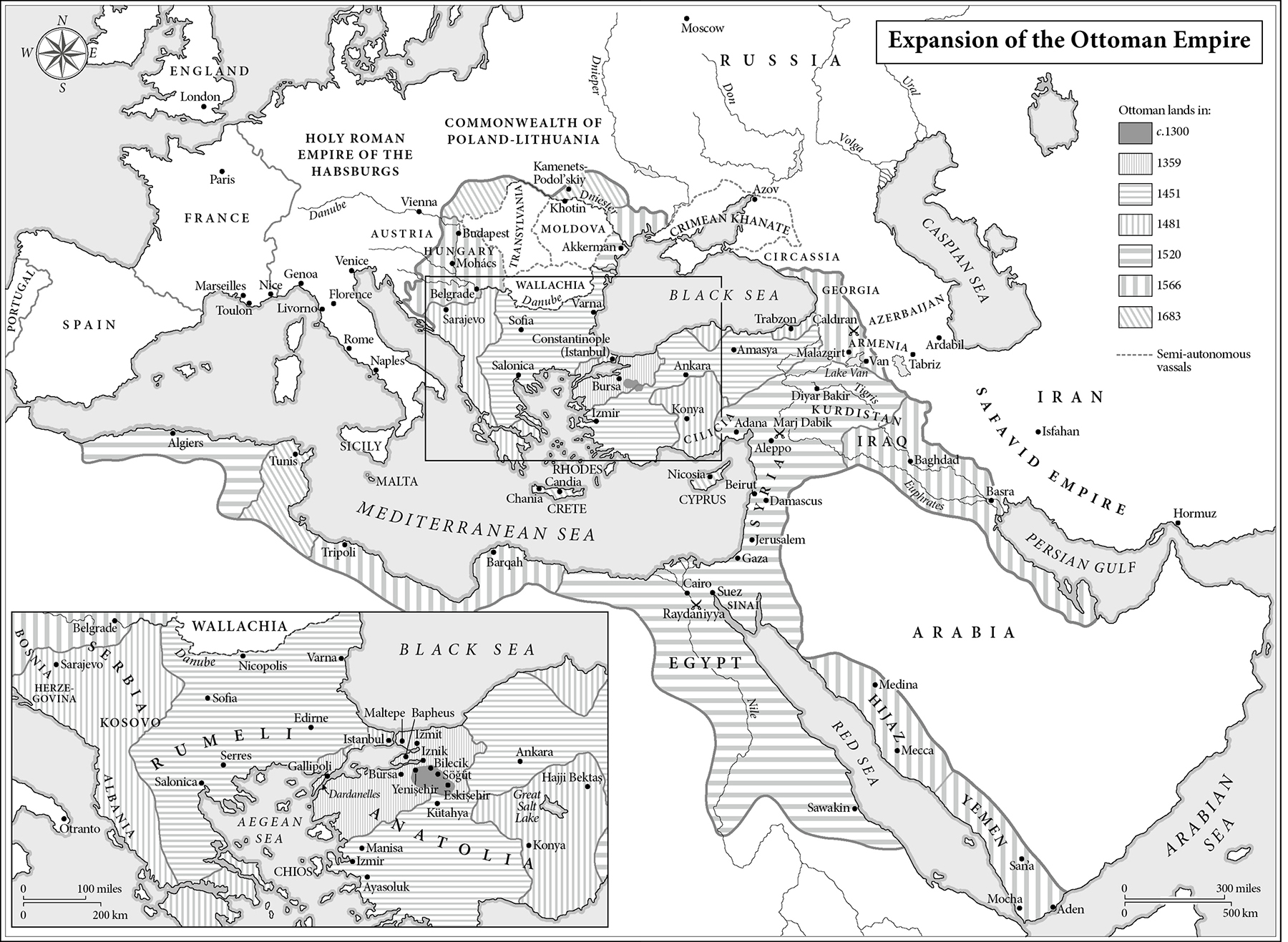

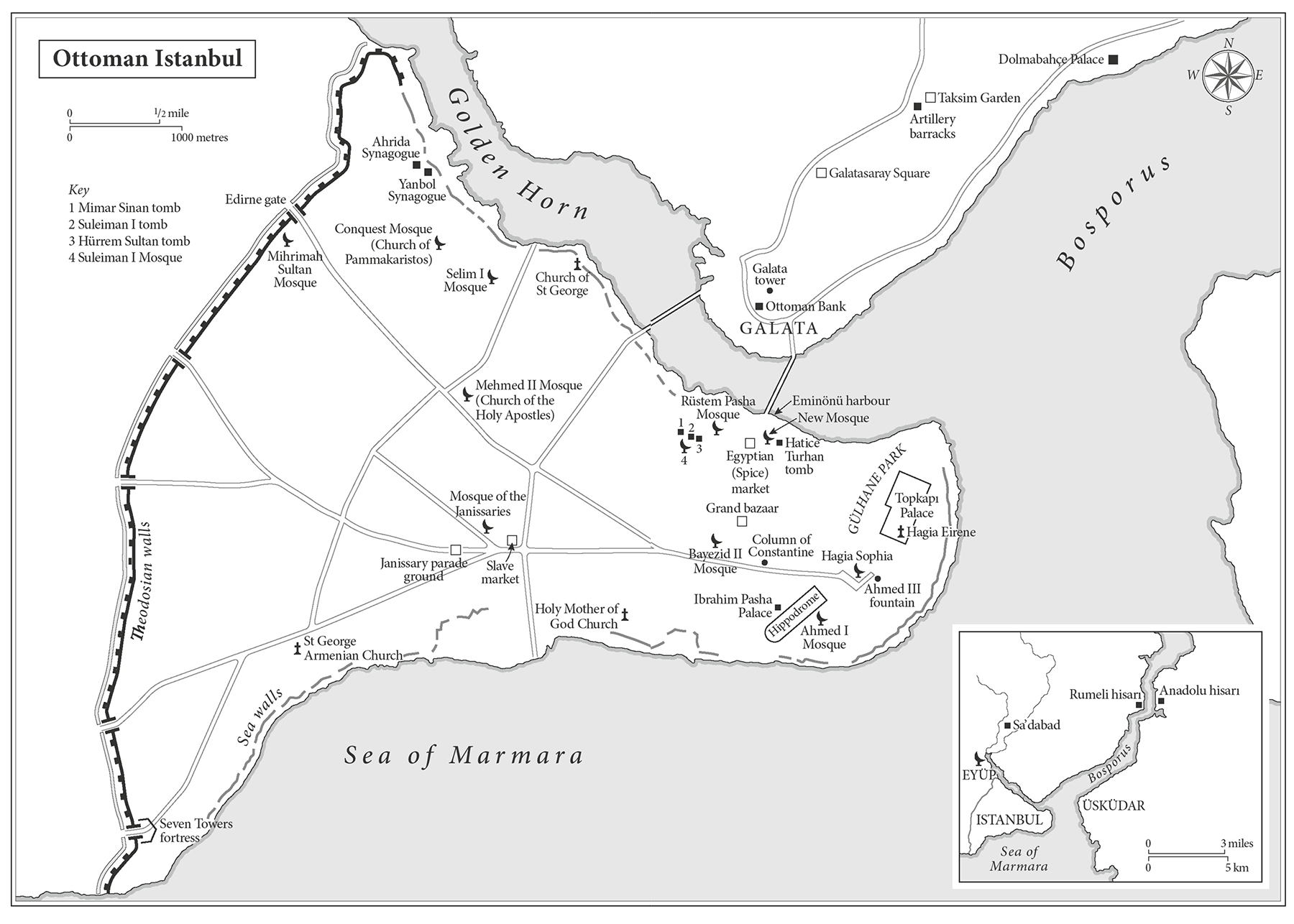

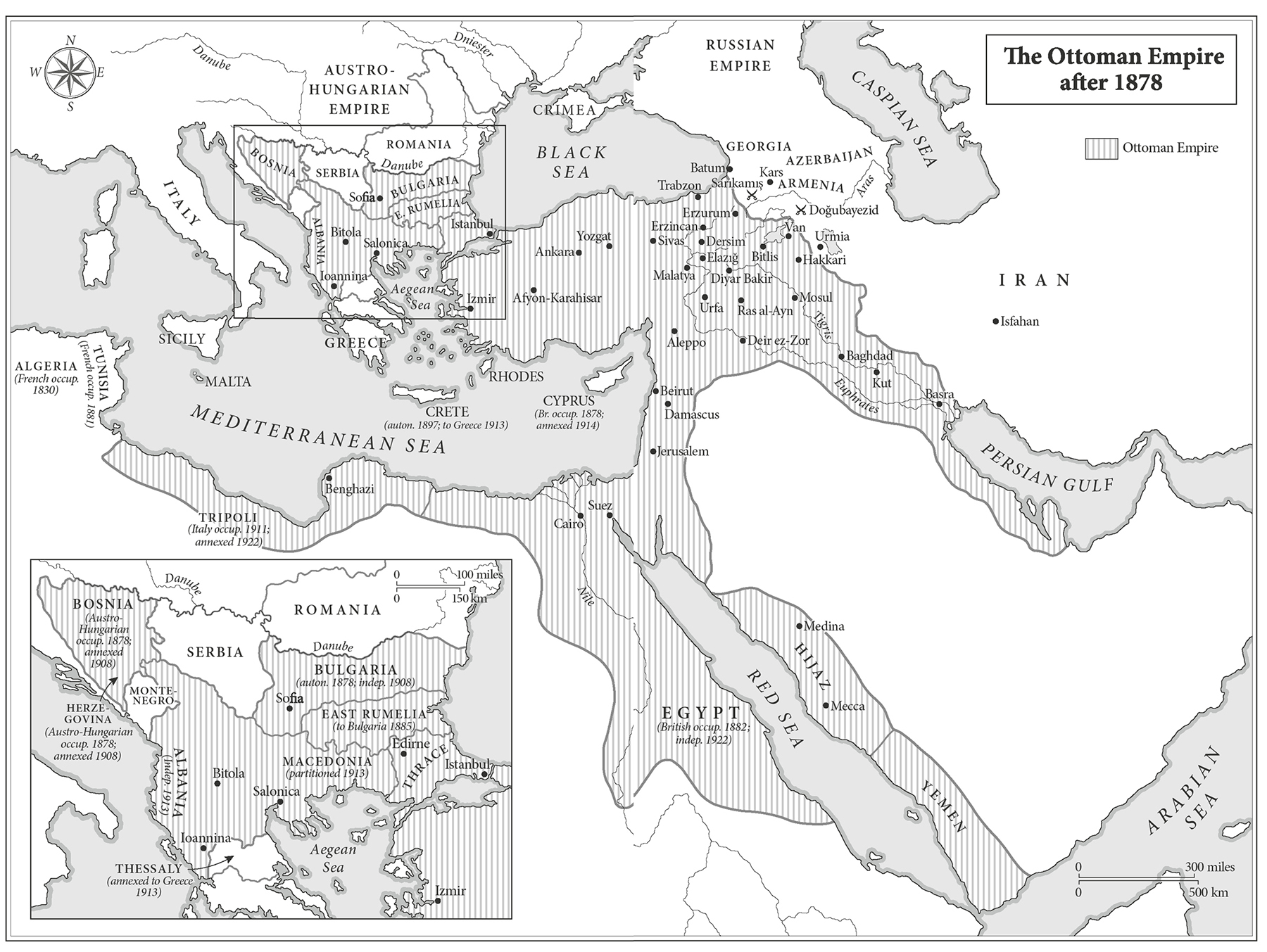

Maps drawn by Rodney Paull.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Baer, Marc David, 1970 author.

Title: The Ottomans : khans, caesars, and caliphs / Marc David Baer.

Description: First edition. | New York : Basic Books, Hachette Book Group, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021004793 | ISBN 9781541673809 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781541673779 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: TurkeyHistoryOttoman Empire, 12881918.

Classification: LCC DR486 .B33 2021 | DDC 956/.0150922dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021004793

ISBNs: 978-1-5416-7380-9 (hardcover), 978-1-5416-7377-9 (ebook)

E3-20210827-JV-NF-ORI

To Esra, Azize, and Firuze

Where are the valiant princes of whom I have told?

Those who said The world is mine?

Doom has taken them, earth has hidden them.

Who inherits this transient world,

The world to which people come, from which they go,

The world whose latter end is death?

The Book of Dede Korkut, medieval epic

To make the book accessible to the general reader, Ottoman and Turkish names have been rendered in modern Turkish spelling, and non-English terms have been translated into English. Those Arabic, Ottoman, and Turkish words generally known in English, such as pasha, sheikh, and the like, are presented in their English forms.

The Turkish letters and their pronunciation are as follows:

c as j in John

as ch in church

is silent; it lengthens the preceding vowel

as i in cousin

as sh in ship

Istanbul or Constantinople? Despite the fact that the name Constantinople was used by the Ottomans themselves, it is convention to call the Byzantine city of Constantinople by that name only until the Ottoman conquest in 1453, and thereafter to use the name Istanbul, which derives from the Greek stin poli (to the city), the name officially given to the city only after the fall of the empire and the birth of the Turkish Republic in 1923. This book follows that convention.

Because the Ottomans used the term Anatolia to refer to Southwest Asia/Asia Minor, this is the term used in this book. Likewise, the region often referred to as the Balkansbut which the Ottomans called Rmeli (land of the Romans)is rendered as Rm. The approximate English translation of this is Southeastern Europe, the term most often used in this book.

H ISTORIANS ARE KNOWN for their love of maps, which illuminate not only the physical contours of their geographic subjects but also the ambitious mindsets of their makers. Over two decades ago, I was conducting research in the Topkap Palace Library in Istanbul for my first book. Off-limits to the hordes of tourists that inundated the palace grounds six days a week, the small library was refreshingly quiet. Located in the former prayer space of a diminutive red-brick mosque built by Mehmed II in the fifteenth century, the library is lined with brilliant blue tiles with intricate green and red floral patterns. A small panel depicts the Kaba at Mecca, the black, cube-shaped shrine that is Islams holiest place. Containing one reading table for researchers and another facing it for staff to watch over them, the room was freezing cold in winter, lacking heat and often electricity. To write or type on a laptop, researchers had to wear thin leather gloves or winter gloves with the fingers cut off. In summer it was cloyingly hot, humid, and dark, the windows shuttered to block out the sunlight, the dust, and the noise.

The reading room offered one ray of hope, for its internal door led to one of the richest manuscript collections in the world, a place only the library staff were allowed to enter. But one had to

Although I experienced an acute case of document jealousy whenever the researchers near me were given a golden illuminated Seljuk Quran or a sixteenth-century copy of Ferdowsis Persian Book of Kings, each scintillating with their brilliantly painted miniatures, nothing was as remarkable as what I saw once thanks to a Japanese television crew filming a documentary on Asian seafaring. One day, I opened the five-hundred-year-old intricately carved mosque door to view the surviving segment of Piri Reiss famous early sixteenth-century world map depicting Spain and West Africa, the Atlantic Ocean, the Caribbean, and the South American coastline, bathed in bright artificial light.

The white-gloved Turkish librarians unrolled it, spreading its gazelle-skin parchment out in the small room, revealing its precious, colourful detail inch by inch to the appreciative camera crew. At his own initiative, Piri Reis of Gallipoli, a former corsair and future Ottoman navy admiral, had drawn one of the earliest surviving maps of the coastline of the New World. He based it on Christopher Columbuss original, which is lost, and even interviewed a crew member from Columbuss voyages. To produce for the sultan one of the most complete and accurate maps in the world, Piri Reis had consulted ancient Ptolemaic, medieval Arab, and contemporary Portuguese and Spanish maps. Imagining themselves as rulers of a universal empire and rivalling the Portuguese in the battle for the seas from Egypt to Indonesia, the Ottomans were interested in keeping up with the latest Western European discoveries. Why werent these connections better known in the West today? Had the Ottomans participated in what is known as the Age of Discovery? What role did they play in European and Asian history?

Like its language, the Ottoman Empire (ca. 12881922) was not simply Turkish. Nor was it made up only of Muslims. It was not a Turkish empire. Like the Roman Empire, it was a multiethnic, multilingual, multiracial, multireligious empire that stretched across Europe, Africa, and Asia. It incorporated part of the territory the Romans had ruled. As early as 1352 and as late as the dawn of the First World War, the Ottoman dynasty controlled parts of Southeastern Europe, and at its height it governed almost a quarter of Europes land area. From 1369 to 1453, the Byzantine city of Adrianople (today Edirne, Turkey), located on the Southeastern European territory of Thrace, functioned as the second seat of the Ottoman dynasty. Constantinople, the capital of the Eastern Roman Empireor Byzantium, remembered as the Byzantine Empireserved as the Ottoman capital for nearly five centuries, beginning with its conquest in 1453. It was not given the new name of Istanbul until 1930, seven years after the establishment of the Turkish Republic amid the ruins of the empire. If for nearly five hundred years the Ottoman Empire had straddled East and West, Asia and Europe, why had its dual nature been forgotten? Had accepted ideas about it changed?