Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

The Emperors of Byzantium

Kevin Lygo

Foreword by Robert Peston

Introduction by Bettany Hughes

The Age of Empires

Edited by Robert Aldrich

Be the first to know about our new releases, exclusive content and author events by visiting

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

www.thamesandhudson.com.au

About the Authors

DIANA DARKE is a cultural expert on the Middle East who has spoken at numerous international events and for the media including the BBC, TRT, PBS, Al-Jazeera and France 24. She is the author of several publications, most notably Stealing from the Saracens, which was awarded Book of the Year in The Spectator and New Statesman, Best Book of 2020 in BBC History Magazine, and was shortlisted for the A+C Book Award in 2021. She is a non-resident scholar at Washington, D.C.s Middle East Institute, with degrees in Arabic and Islamic Art & Architecture.

Contents

It is time, a century on from the dismemberment of their empire following the First World War, to look afresh at the Ottomans. They lived in a world very different from our own, yet there is much we can learn from the way they structured their societies, just as there is much to appreciate in how their unique achievements have enriched our lives.

The global context must be understood when we attempt to piece together the Ottomans legacy quite a challenge when even modern Turkey, the successor state to the Ottomans, has a lovehate relationship with its Ottoman past. In considering a 600-year empire that straddled Europe, Asia and Africa, and encompassed an enormous diversity of peoples, there will inevitably be both good and bad. Every world empire, not least the British, had its share of lived tragedies.

Equally fallacious is to apply todays lexicon to events of the past. Expressions such as the Turkish yoke and multiculturalism represent two extremes. The first was invoked by 19th-century nationalist paradigms, while the second is loaded with 21st-century overtones that did not exist in Ottoman times. Prejudice is part of the picture, and history is written by the victors, so theirs is the view that inevitably seeps into our consciousness. This book does not seek to pass judgment on the Ottomans one way or the other, or to exonerate them from what were clearly violent acts. Yet it is as if, as a people, they have disappeared. I am struck by the fact that the word Ottoman rarely figures in the index of most guidebooks to Balkan countries; where it does, the reader is referred instead to the entry for Turkish domination, perpetuating the narrative of an oppressive rule by a detested alien power. The education systems of most Balkan countries do likewise, ensuring that new generations grow up with the same mindset, since modern European nationalist views based on religion and language necessitate the rejection of all things Ottoman.

Genealogical tree of the Ottoman sultans, produced in 186667, during the reign of Sultan Abdulaziz. The imagery of the entire dynasty bursting forth from a single tree reflects Osmans visionary dream. In a fertile landscape of rivers and hills that resembles St, where he first founded the Ottoman dynasty in todays western Turkey, he is said to have seen the enormous plane tree grow from his own navel to encompass the whole world.

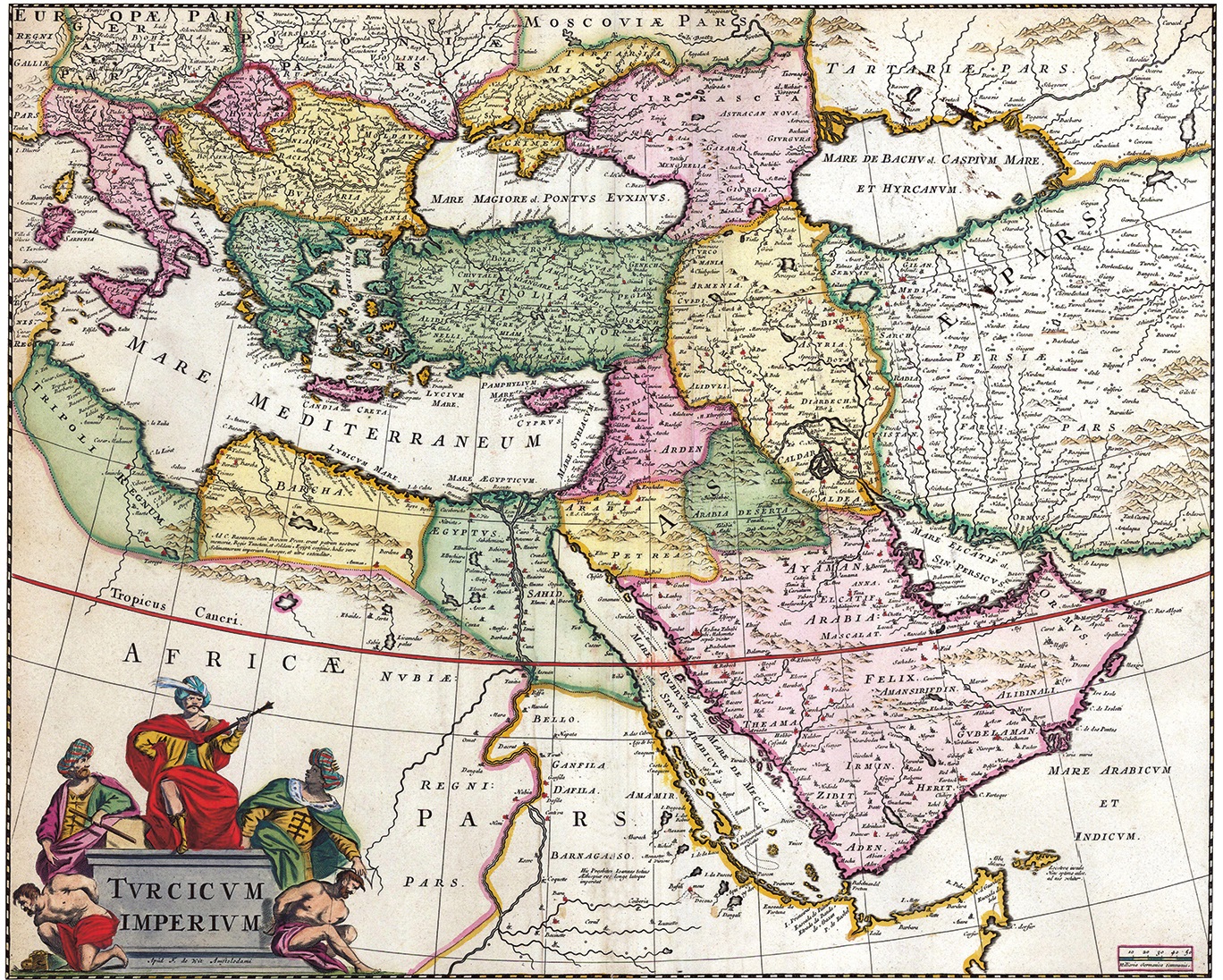

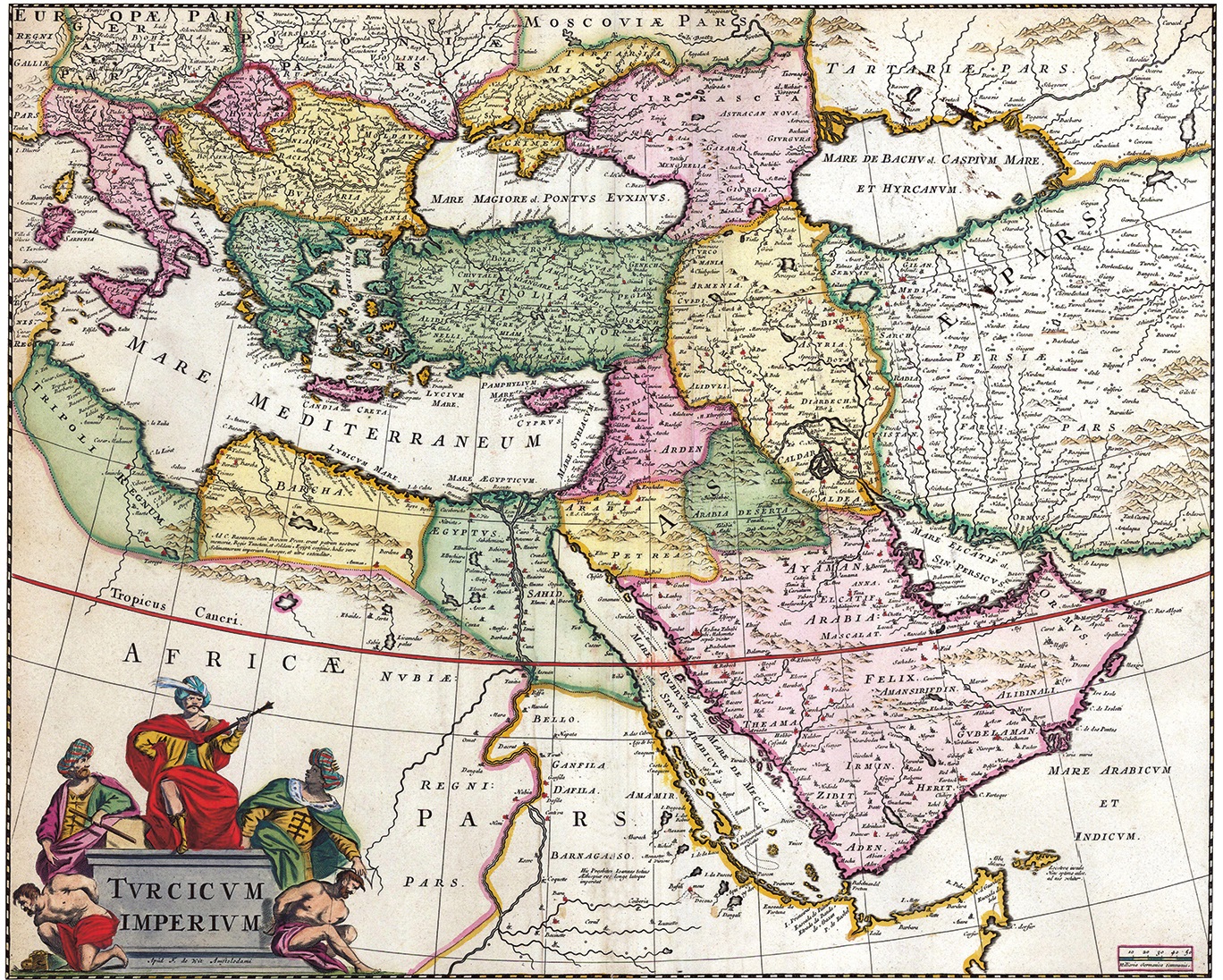

A map of the Ottoman Empire by Frederick de Wit, c. 1680. It was published on the eve of the Great Turkish War (168399), which marked a turning point in the empire's fortunes. With the Treaty of Karlowitz, signed in 1699, Turkey ceded control of all of Hungary, and areas in the Balkans and Transylvania, to Austria.

Across the provinces of the Arab world that were once under Ottoman rule, opinions on the period are more nuanced. Although Ottoman Turkish was the language of court judgments and was still used by the army and police into the early 20th century, Arabic remained one of the official and literary languages, and Ottoman cultural influence was minimal across the Maghreb. In Tunisia, after French colonialists imposed a protectorate in 1881, local people are said to have scanned the horizon hoping to see Ottoman ships arriving again. In Syria and Egypt, views of the Ottomans wax and wane according to the politics of the day. The Syrian governments view, for example, was broadly positive in the days when Turkeys President Erdoan and Syrias President Assad used to holiday together. When the two fell out in 2011 after Turkey supported the Syrian opposition, the official school history syllabus was changed to refer not to the Ottoman era but to the Ottoman occupation.

The Ottomans ruled over an area more extensive than the Byzantines, and for a longer period than the Romans. Their empire was in many ways the successor to Byzantium, in the same way that the Byzantine Empire was the successor to Rome. All three empires were based in the Mediterranean and used long-lasting institutions to rule over a diverse assemblage of ethnicities, religions and cultures, therefore representing the very opposite of todays nation-state.

Yet, unlike the Roman and Byzantine empires, whose legacies have been described exhaustively by generations of European historians, the cultural heritage left by the Ottoman Empire has often been neglected, sometimes even wilfully ignored. This has been exacerbated by academics traditionally shying away from such a lengthy time period and such a vast geographical area. Some focus only on the Arab provinces, others only on the Balkans. Some are scholars of Turkish, others of Hellenic or Byzantine Studies. The result is a fragmentation of knowledge. For the sake of the general reader, therefore, my aim here is to venture a broader overview of the Ottomans and their historic influence, covering the fields of commerce, society, religion, science, music, language, literature, cuisine, and home and lifestyle. My approach is thematic, so that I can showcase this enormous diversity, enriched by the books carefully chosen illustrations.

Ottoman map of the Maghreb and Middle East, late 16th century, marking Africa, Egypt and the Mediterranean islands like Cyprus, Rhodes and Crete in Ottoman Turkish.

Putting together the pieces of this Ottoman legacy has proved a challenging and complex puzzle. Like many in the West, I did not realize how European the Ottomans were. I was surprised to learn, for instance, that, when Constantinople was conquered in 1453, it was not by Muslim hordes advancing from the steppes of Asia, but by a mixed MuslimChristian army already based on the European mainland. For over a century, a quarter of the Ottoman Empires territory lay within what today is Europe, yet such boundaries as existed in the European mind were never shared by the Ottomans. Even during the second siege of Vienna in 1683, 100,000 Hungarian Christians fought on the Ottoman side, as did thousands of Greeks, Armenians, Slavs and Transylvanian Protestants, disenchanted with the Catholic fervour of the Habsburgs and the feudal levies of their own aristocrats. That is not to say that either side were angels, of course, but the narrative in which a valiant Christian Europe battles against a despotic Muslim Orient is a Disney version of history. MuslimChristian collaboration and coexistence were present to an extraordinary degree despite the religious wars of propaganda painted by both sides.

Next page