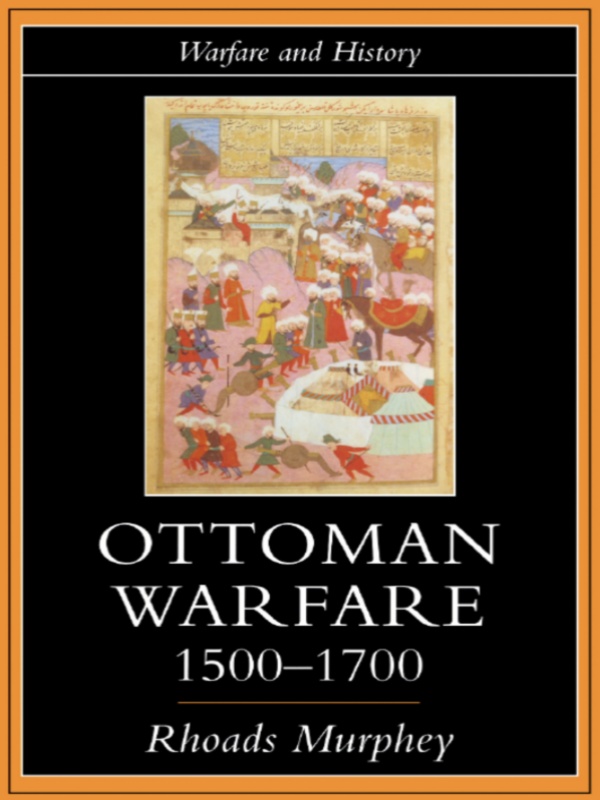

Warfare and History

General Editor

Jeremy Black

Professor of History, University of Exeter

Published

European warfare, 16601815

Jeremy Black

The Great War, 191418

Spencer C. Tucker

German armies: war and German politics, 16481806

Peter H. Wilson

Ottoman warfare, 15001700

Rhoads Murphey

Wars of imperial conquest in Africa, 18301914

Bruce Vandervort

Forthcoming titles include

War and Israeli society since 1948

Ahron Bregman

Air power in the age of total war

John Buckley

English warfare, 15111641

Mark Charles Fissel

European and Native American warfare, 16751815

Armstrong Starkey

Seapower and naval warfare

Richard Harding

Vietnam

Spencer C. Tucker

Rhoads Murphey, 1999

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved.

Published in the UK in 1999 by UCL Press

UCL Press Limited

Taylor & Francis Group

1 Gunpowder Square

London EC4A 3DE

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2001.

The name of University College London (UCL) is a registered trade mark used by UCL Press with the consent of the owner.

ISBNs: 1-85728-388-0HB

1-85728-389-9PB

British Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 0-203-01597-5 Master e-book ISBN

ISBN 0-203-17347-3 (Glassbook Format)

List of illustrations

Army market place, ordu bazar

Men pulling field cannon

Besieging a fortress in the Yemen

Banquet given in honour of the commander before departure on the eastern campaign

Departure of Osman IIs army from Istanbul on the campaign against Hotin in 1621/1030 H. Religious officials carrying banner of the prophet Muhammad, the alem-i serif

List of tables

Increase in Janissary ranks shown as a proportion of all salaried staff

Increase in salary payments to the Janissaries shown as a proportion of total salary payments

Proportion of armys time spent in rest and march (comparison of European and Asian spheres of operation)

Potential strength of timariot army circa 1527

Potential strength of timariot army circa 1631

Prescribed/putative size of the timariot army in 1609

Annual treasury payments for the salaries of the sultans standing troops and other (mostly non-military) palace staff

Size and composition of sultans standing army (kapu kulu) 15271670

Figures contrasting total potential Janissary strength with numbers actually deployed in battle

Treasury savings from reductions in the ranks of the permanent standing cavalry regiments 160992

Costs for garrisoning fortresses in newly-conquered Ottoman provinces in the Caucasus circa 1585

Requisition and purchase of camels for army transport at the time of the Erivan campaign of 1635

Data on grain transport by ox cart showing the typical load factor for oxen

Per kile/per kilometre transport costs (in akes) using various modes of transport

Maps

The Ottoman position in the West at the end of the seventeenth century

The Ottoman position north of the Black Sea

3. The Ottoman position in the East at the turn of the seventeenth century

Distance of potential battlefields with reference to Istanbul

River systems of Hungary

Preface: Scope and purpose of work

The period 1500 to 1700 forms a period of Ottoman dynastic history when the Ottomans gave particular emphasis to their frontiers with Europe. While other fronts were activated against Iran in 1514, Syria and Egypt in 1517, and into the lower Tigris-Euphrates in the decade following the Ottoman capture of Baghdad in 1535, from the fall of Buda in 1541 to the close of the seventeenth century the Ottomans were most consistently concerned with the defence (and, periodically, the extension) of their trans-Danubian possessions. This channelling of Ottoman effort was the product (and an Ottoman response to) contemporary political circumstances. While the rise of the Safavid dynasty in the East from 1502 posed a potential threat to the Ottomans, the unification of the crowns of Spain and Austria under Charles V from 1519 posed a present and real danger to Ottoman strategic interests. Despite the redivision of territories at the abdication of Charles in 1556 and the succession of his brother Ferdinand (the First) to his eastern possessions and of his son Philip (the Second) to his western and northern possessions, the Ottomans had by that time irreversibly committed themselves to anti-Habsburg alliances and strategic positions of their own that kept them at the centre of Middle European politics until the end of the seventeenth century. While it will not be possible, given the wide scope of our coverage of general military developments over a two-century period, to focus in detail on developments in any one of the lands that formed the post-1540 Ottoman empire, a natural bias towards events on the northwest frontier represents the actual pattern of Ottoman military involvements in the period. Of the three most active fronts the Caucasian, the Mesopotamian and the Hungarian it was the latter which persistently claimed the lions share of Ottoman resources and concentration of effort.

The sheer size of the post-1540 Ottoman empire necessitated such a balancing of interests and commitments. Resources and surpluses from one area were used by the Ottomans to good effect to subsidize and support military activity in another, and for most of the period the empires size was a source, not of increased vulnerability, but rather of strength. From the mid-sixteenth century the Austrian military border along the northwest frontier, forming a 370-mile arch extending from Kosice on the north and east to Senj in the south and west, was guarded by a string of more than 50 forts and fortresses. By 1600, with the addition of Kanice (Nagykanizsa) as the fourth province of Ottoman Hungary, the Ottomans were able to match the Austrians in number and kind, and the balance struck in the early years of the century was little changed until the 1660s. At the other extreme, although the Ottoman-Safavid frontier stretched over 600 miles from Batum on the Black Sea to Basra on the Shatt al-Arab, only a small proportion of the full extent was very heavily garrisoned or defended. Apart from confined periods of exceptional activity (as for example during the 1580s and again in the 1630s) the costs of maintaining the Ottomans presence in this sphere could be offset by relying mostly on local resources. In view of these realities, the weight of evidence which we will draw upon for our narrative comes from the mid-sixteenth century onwards and predominantly from the European sphere of operations. References to events affecting other spheres and periods are unsystematic and included mostly to highlight parallel institutional developments or as illustrations of general phenomena.