Orthodoxy and Islam in the Middle East

Orthodoxy and Islam in the Middle East

The Seventh to the Sixteenth Century

By Constantin A. Panchenko

Translated by Brittany Pheiffer Noble and Samuel Noble

HOLY TRINITY PUBLICATIONS

Holy Trinity Seminary Press

Holy Trinity Monastery

Jordanville, New York

2021

Printed with the blessing of His Eminence, Metropolitan Hilarion First Hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia

Orthodoxy and Islam in the Middle East:

The Seventh to the Sixteenth Century

2021 Holy Trinity Monastery

ISBN: 978-1-942699-33-0 (paperback)

ISBN: 978-1-942699-35-4 (ePub)

ISBN: 978-1-942699-36-1 (Mobipocket)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020949696

Cover Images: The seizure of Edessa in Syria by the Byzantine army and the Arabic counterattack Scan from illuminated manuscript the Chronicle of John Skylitzes: National Library, Madrid, Spain. Source: commons.wikimedia.org, Cplakidas; MAP: Asia Minor Vintage Map by Sergey Kamshylin.

Source: stock.adobe.com.

All rights reserved.

I do not cry for the king of this world but I cry and weep for the believing people, for how the Almighty, holding the whole world in his palm, despised His flock and He forsook his people for their sins.

Antiochus Strategos, 631

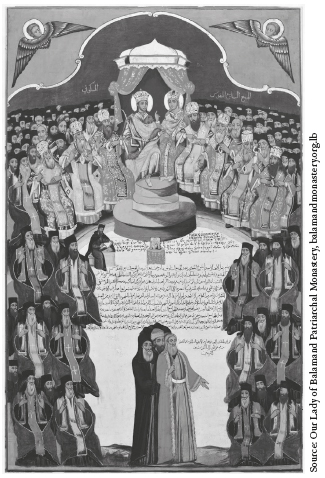

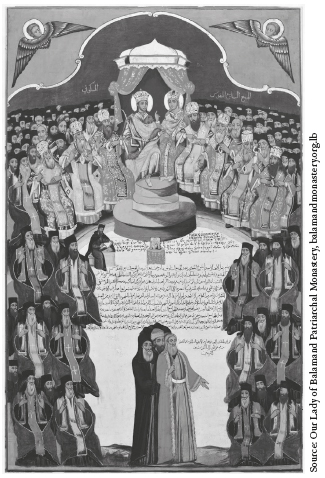

Eighteenth-century icon of the Aleppo School depicting the Seventh Ecumenical Council, the acts of which preserved the epistle of Patriarch Theodore of Jerusalem to the patriarchs of Alexandria and Antioch, justifying the veneration of relics and icons. The Arabic text in the center of the icon is taken from a history of the council and begins, In the name of our Lord, God and Master Jesus Christ, one hundred and fifteen years after the Sixth Council, the Seventh Holy Council was held in Nicaea. The representatives of the three Eastern patriarchs are portrayed in the middle of the assembly, including the syncellus John and the abbot Thomas, who actively supported the councils decisions.

Contents

Foreword

W e are pleased to offer in this concise study a broad survey of the life of the Orthodox Christian communities in the Middle East from the emergence (advent) of Islam in the early seventh century through the following nine hundred years. For those of us living in the modern West, this will open up a world that to all practical purposes is unknown to us: a world where many forms of Christianity existed (and still exist) and where conflicts between different Islamic tribes and dynasties create a tableau of great complexity and many contrasts.

The diligent reader will learn of overt persecution and martyrdom of Orthodox believers at the hands of both Muslims and pagans, together with suffering at the hands of the Latin Crusaders. But they will also see that this was not their constant reality and that in perhaps equal measure times of peaceful coexistence prevailed. Further, beyond these polar-ities of persecution and peace, attention is given to changes in the physical environment and other calamities such as plague and earthquake that were to bring about lasting changes in the life of the Church. In this respect, for all of us now living in a time of worldwide epidemic, the sufferings that are recounted here should put our own in perspective. Through all of these events and in the light of the fragility of the life of so many who lived through them, we can see that it is all the more a testament to Gods work in history that in our own time these communities still exist and flourish, perennially renewed by the life of Christ in His Church.

Through the kaleidoscope of this work the reader will gain a vision of some of the seminal tides of human history that shaped and continue to mold both the region of the Middle East and the wider world to which it ultimately belongs as the cradle of civilization. As such we hope it will shape the understanding not only of those engaged in formal academic studies but of a wider readership as well.

Holy Trinity Monastery, September 2020

The Arab Conquest: Christians in the Caliphate

T he seventh century, the time of the Arab conquests, was the most dramatic landmark in the history of the Christian East. Boundaries between civilizations that had remained immutable for seven centuries were swept away within nine years. The global crisis of Late Antique

Heretics who were persecuted in Byzantium clearly preferred the authority of the Muslim caliphs, for whom all Christian confessions were equal. The Orthodox of the Middle East (Melkites

It should be recalled that the Muslim doctrine of the era of the rightly guided caliphs

In the seventh and eighth centuries, Christians still made up the majority of the population in the lands of the Caliphate from Egypt to Iraq. At the same time, Islamization

Because of their level of education, some dhimmis managed to obtain a high social position in the Caliphate. Non-Muslims had a strong position in trade and finance, practically monopolized the practice of medicine, and almost completely filled the ranks of the lower and middle levels of the administrative apparatus. Christian, including Orthodox, doctors and administrators were of great importance at the caliphs court. Masterpieces of Arab architecture of the late seventh and early eighth centuries were created by Christian craftsmen according to Byzantine techniques. The Umayyad period (661750 ad ) is considered the last flowering of Hellenistic art in the Middle East.

The Fading Inertia of Byzantine Culture in the Seventh and Eighth Centuries

The Arabs had no experience managing a developed urban society and gladly made use of the services of former Byzantine officials in their tax administration. Before the eighth century, bureaucratic documents in Syria and Egypt were written in Greek. Part of the non-Muslim elite was closely associated with the ruling circles of the Caliphate. It is noteworthy that in contrast to the obvious presence of Jews and converts from a Jewish milieu in the entourage of Muhammad and the rightly guided caliphs, it was Christians who played a significant role under the Umayyads.

The governors (emirs) of provinces were almost completely independent. The caliph could change them, but he could not intervene in their affairs. This semi-autonomous status of the provinces ensured a maximal preservation of the traditional way of life and political stability. The system of tax collection and distribution of pay to soldiers were decentralized. The imperial center only received very little of the surplus revenue from the provinces. The old regional elites remained in place and the Arabs did not encroach on their authority, remaining content with collecting taxes.

Archaeological research in Palestine and Jordan in recent decades gives a picture of almost universal Christian presence in the cities of the Middle East in the seventh and eighth centuries, with Byzantine traditions of urban

The best preserved architectural monuments of Umayyad Christianity include Umm al-Jimal in northeastern Jordan where fourteen churches and two monasteries were active in the seventh century; two dozen churches and seven monasteries were close by. At the beginning of the seventh century, there were more than fifteen churches in Jerash (Gerasa), to which only one mosque was added in the Umayyad period. Many churches in northwest Jordan were rebuilt during the era of the Caliphate and continued to be used until the Mamluk era (12501517 ad ). In the village of Samra near Jerash, the mosaics of three churches date back to the beginning of the eighth century. Hundreds of Christian funerary stelae with inscriptions in Greek and Aramaic have also survived. In Madaba, there are Greek inscriptions mentioning the bishops and construction activity up to 663. In Ramla,

Next page