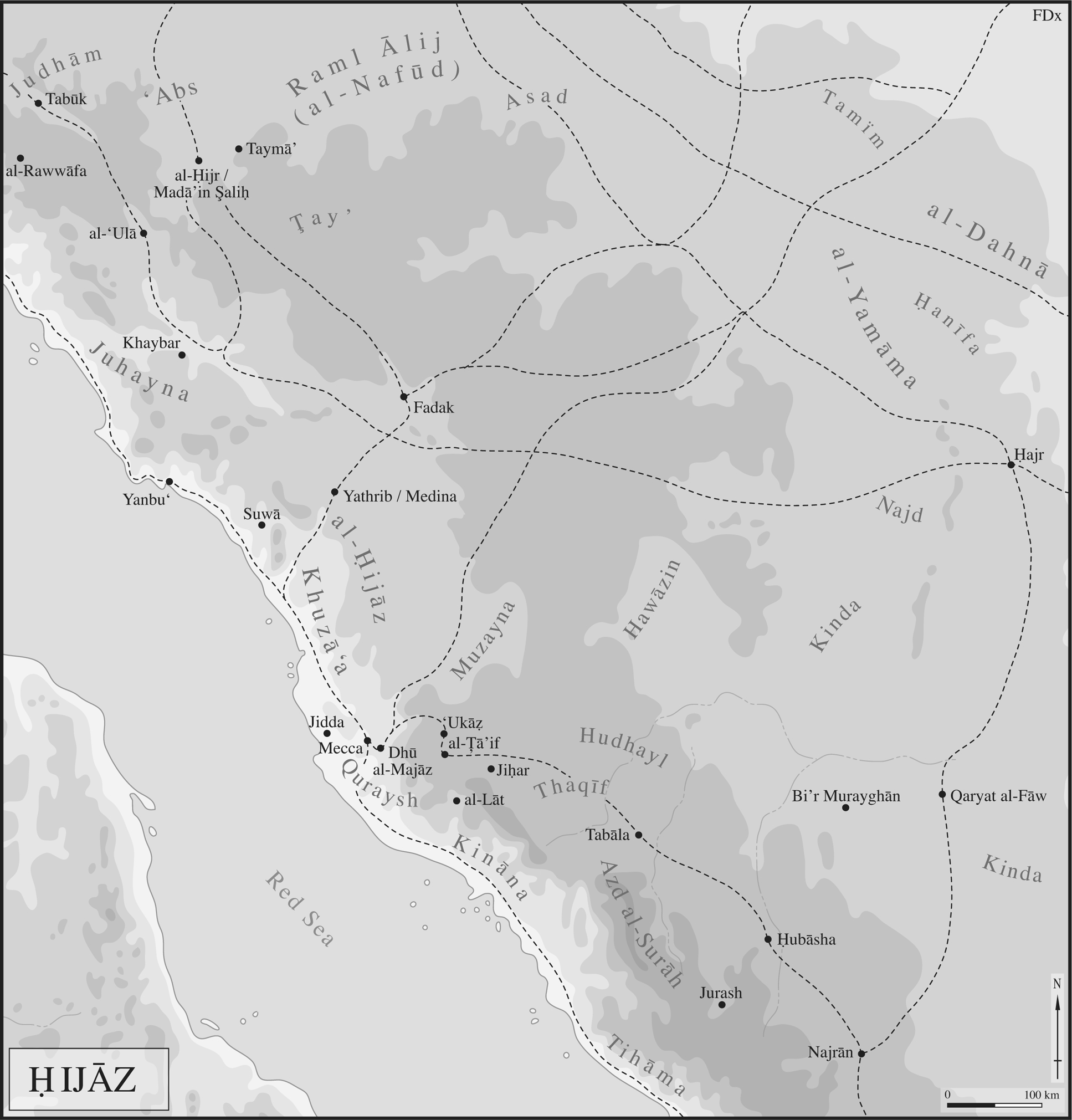

Map of Southwest Arabia, prepared by Fabrice Delrieux.

Map of the ijz, prepared by Fabrice Delrieux.

THE FAITH THAT drove the armies of Arabs out of the Arabian peninsula to take possession of Palestine, North Africa, and Syria within a few decades in the first half of the seventh century remains today a powerful force in world affairs. What generated this force is as obscure now as it was in the beginning, and historians have been impeded by the tendentious character of most of the sources for this great upheaval, as well as by their own prejudices. It is difficult for non-Muslims, above all Jews and Christians, to be dispassionate in confronting the tide of Muslim conquests that swept over the ancient cultures of the Near East. It is no less difficult for Muslims to apply scholarly rigor to the word of God as well as to a historiographical tradition that significantly postdates the events it records. Yet in view of the immense authority of Islam in the modern world it becomes more imperative than ever for both sides to make the effort.

The pioneering generation of Islamicists in the West, including Theodor Nldeke, Julius Wellhausen, and Ignaz Goldziher, applied the methods of classical philology as they had been successfully imported into the study of the New Testament and the Hebrew Bible by Erasmus and Gesenius. As these scholars recognized, the transmission of these old texts was susceptible to critical analysis, which in the fullness of time could be supplemented by surviving documents on stone, papyri, and coins, and eventually the discoveries of archaeological excavation. For Islam the authority of the Qurn, being the revealed word of God, notoriously resisted the Erasmian challenge, because of the vast hiatus between its creation, at whatever time and by whatever means, and very much later reports of the context from which it came. It took nearly two centuries for Islamic exegetes to acquire a corpus of what was known about the genesis of their religion. By then a complex process of textual contamination was already in place. During those two centuries non-Muslim chroniclers, interpreters, and historians had been at work in a variety of languagesGreek, Latin, Armenian, Syriac, and Arabic above all. They had conspicuously exploited one anothers material, which left traces of their borrowing in the texts they wrote, but naturally they had their own doctrinal perspectives.

Three recent books illustrate the dilemma facing anyone looking into the crucible in which Islam was forged. By their very diversity, these three accounts of the rise of Islam illustrate the problems inherent in telling this story.

Fred Donner, in his Muhammad and the Believers, explains what happened in an essentially chronological narrative that commingles quotations from the Qurn and various early documents with testimony from the traditional Muslim sources of several centuries later. He consciously writes with an eye to providing a generally sympathetic and generous view of the early Muslims that might be acceptable in the fraught politics of today. Hence his insistence on calling them the Believers, which is, to be sure, a perfectly correct rendering of the term that was often used for the followers of Muammad. He thinks that the community of Believers was considerably more ecumenical than many other historians have thought and that it was both open to contact with Jews and Christians and receptive of their views. Readers have been quick to notice that Donners account of Islamic origins portrayed a first generation of Muslims who seem much less menacing than they appeared to the Jews and Christians at the time, or to most historians since. But he does not avoid the many divisive and sanguinary encounters that the Believers had with others and even with many of their own.

In his history of the Arab conquest and the creation of an Islamic empire, In Gods Path, Robert Hoyland has reasonably adopted an approach that largely rejects treating later and tendentious texts as sources for the formative age of Islam. These are not only Arabic texts of the adth, but equally Arabic historiography (above all al-abar), Arabic Christian historiography (such as Agapius), numerous Syriac chronicles, and Greek histories such as the vast Chronographia of Theophanes Confessor, who relied upon sources now lost that were themselves dependent upon sources that were already lost when he was writing. Because Muslim historical sources are missing until the ninth century, Hoyland chose to confine himself to those extant texts that came only from the first two centuries of the Islamic era. Their authority would accordingly derive from their closeness to the events they describe.

But this is a risky methodology. These are inevitably Christian and Jewish sources, which are close to the events they describe but more directly colored by them. They tend to display a predictable undercurrent of antipathy to the Muslims. Hoyland compensates for this weakness by adroitly turning to the peripheral nations that impinged upon Muslim territory. In this way he gains a broader perspective for the events of the period. Hence he looks farther afield to Georgia, Armenia, and Central Asia, and by comparison can track whatever malice or error the contemporary or near-contemporary writers in the Near East itself might have been inspired to import into their narratives.

The great peril in Hoylands approach is the potential loss of genuinely illuminating information that might lurk in those later Muslim accounts. A historian must always be alert to the tendentiousness of sources but is not always justified in discarding them altogether. What is required is a meticulous examination of multiple tellings of the same story in an effort to determine its outlines as well as the deformations to which it has been subjected. This is exactly what Maria Conterno has done, in exemplary fashion, in her analysis of the sources that lay behind the narrative of Theophanes for the two centuries before his time.