Contents

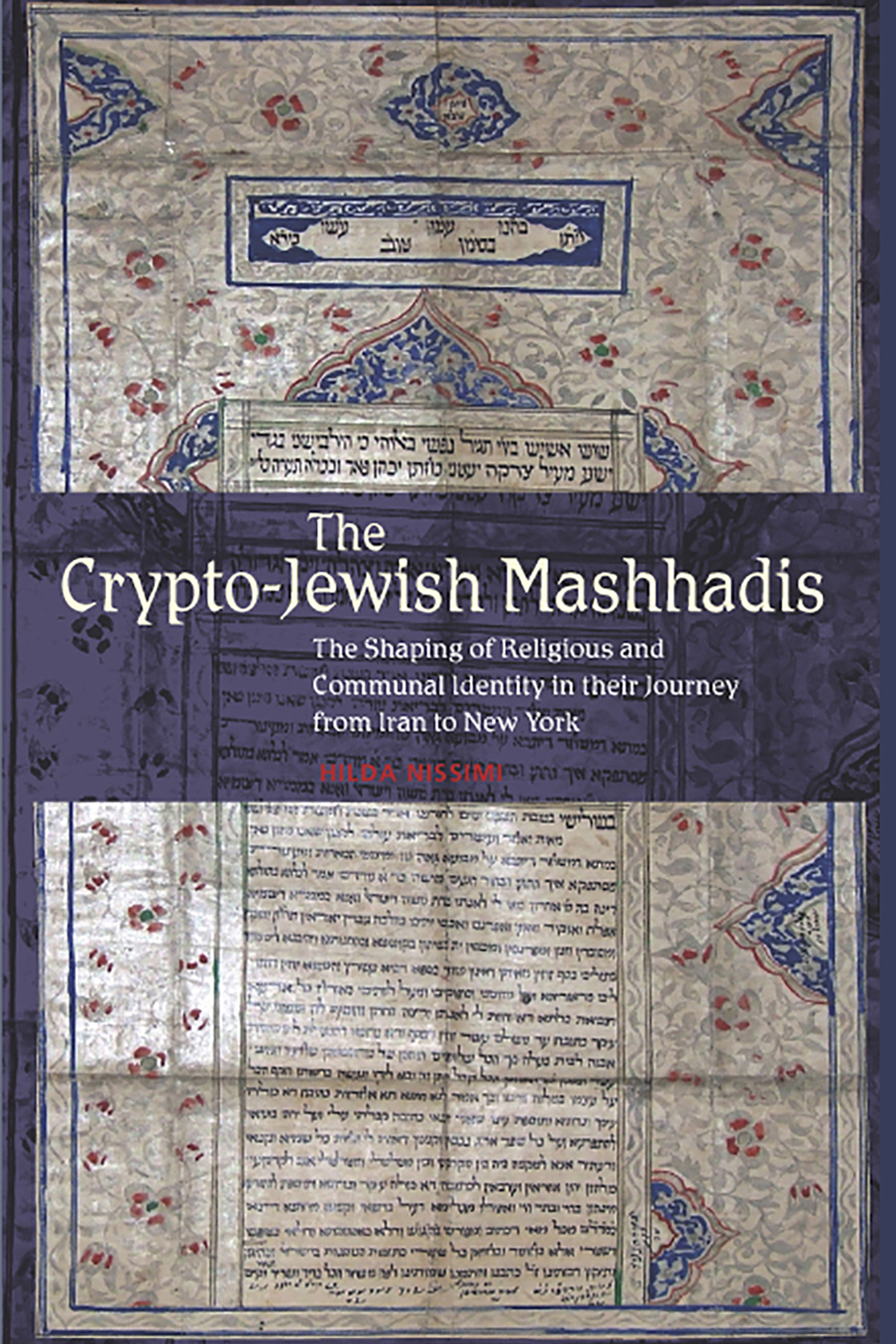

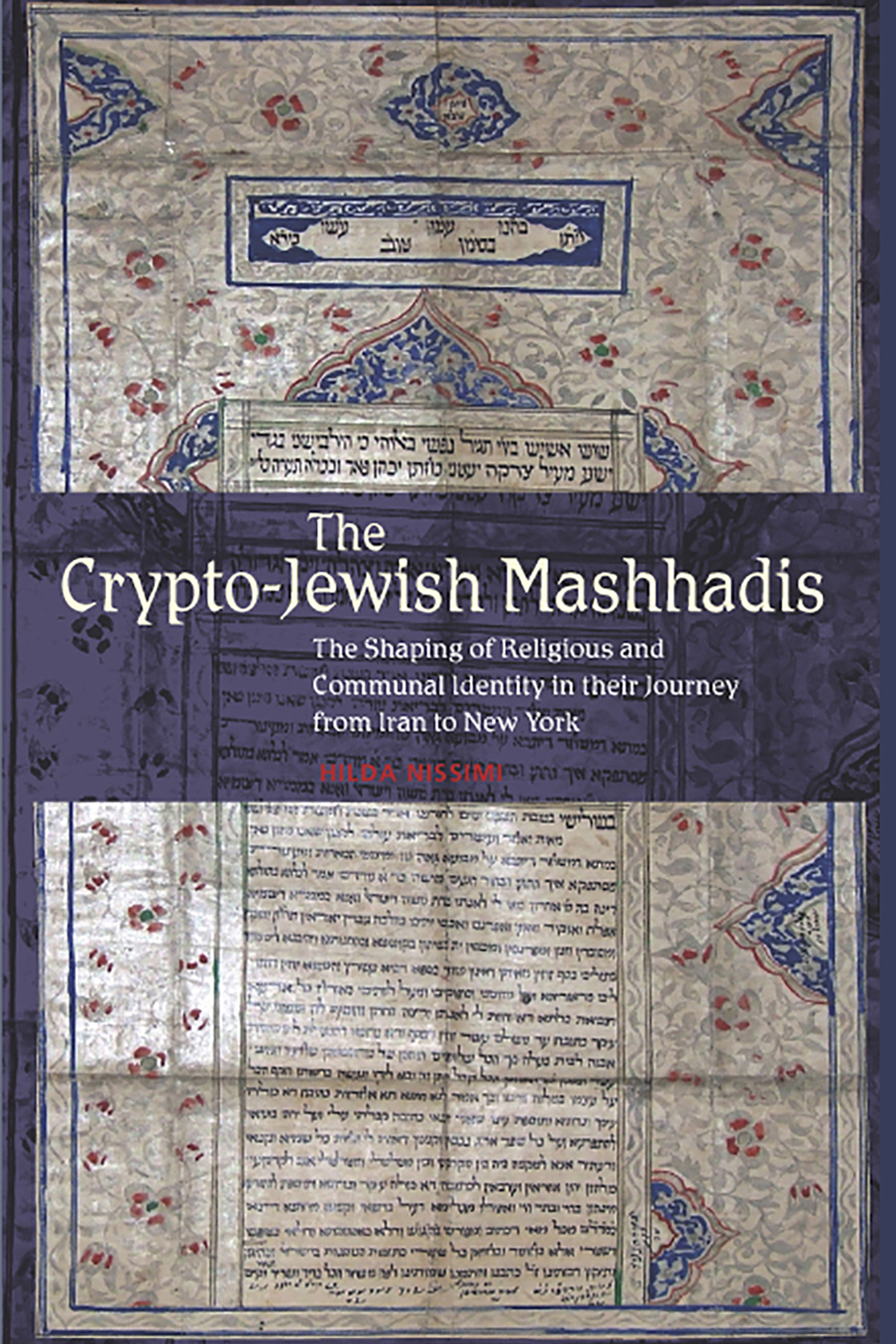

The

Crypto-Jewish Mashhadis

This book is dedicated to

The memory of

my mother and father-in-law, Malka and Michael,

who have embraced me into their family,

allowing me to make it my own.

To my husband Reuven, and my children,

Malka, Yair and Michael,

for making everything worth it.

And foremost to my own parents,

Miriam and Yeshaayahu Schatzberger,

To whom I owe it all.

The

Crypto-Jewish Mashhadis

The Shaping of Religious and

Communal Identity in their Journey

from Iran to New York

HILDA NISSIMI

Copyright Hilda Nissimi, 2007.

Published in the Sussex Academic e-Library, 2020.

SUSSEX ACADEMIC PRESS

PO Box 139, Eastbourne BN24 9BP, UK

Ebook editions distributed worldwide by

Independent Publishers Group (IPG)

814 N. Franklin Street

Chicago, IL 60610, USA

ISBN 9781845191609 (Paperback)

ISBN 9781789761245 (Trade Paper)

ISBN 9781782847298 (Epub)

ISBN 9781782847298 (Kindle)

ISBN 9781782847298 (Pdf)

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This e-book text has been prepared for electronic viewing. Some features, including tables and figures, might not display as in the print version, due to electronic conversion limitations and/or copyright strictures.

Foreword by Houman Sarshar |

The Jews of Iran have been living in that land for over 2,700 years. During this time they have consistently remained the single largest community of Jews anywhere in the Middle East outside present-day Israel. In this period, during the millennium that started with the rise of the Achaemenid dynasty ca. 560 BCE and ending with the end of Sasanian rule ca. 650 CE , they not only contributed to Jewish history with among other things the rebuilding of the Second Temple, but more importantly they made some of the most significant contributions to Judaism itself with books in the Neviim and the Kethuvim and, even more importantly, the compilation of the Babylonian Talmud, the venerability of which in Jewish law is second only to the Torah. Yet, in what is surely one of the more mysterious enigmas of Jewish studies, the Jews of Iran have also consistently remained one of the least studied families of world Jewry.

Though some works were published during the first half of the twentieth century, the existing body of Judeo-Persian scholarship was written mostly in the past fifty years with monumental works like Habib Levis three-volume The History of the Jews of Iran and Jacob Neusners five-volume A History of the Jews in Babylonia . To be sure, a broad range of articles and other books have further enriched the field, but compared to the historical scope of Jewish presence upon the Persian plateau the scholarship continues to be disproportionately scarce. Moreover, contemporary Judeo-Persian studies further suffers from the fact that the overwhelming majority of existing scholarship in the field is predominantly comprised of essentially primary sources such as archeological, historical, or even cultural studies that, though replete with unquestionably invaluable factual data, nevertheless often prove lacking in a level of theoretical analysis that can potentially bring to light nuances about Judeo-Persian history and culture that might remain otherwise obscure. Hence the merit of the book at hand.

Hilda Nissimis book is a valuable and worthy contribution to what is gradually emerging as a new and much needed phase in Judeo-Persian studies brought about by a new generation of scholars who are expanding on the work of previous archeologists, historians, and anthropologists to shed light on previously overlooked nuances of what it meant, and indeed of what it means, to be an Iranian Jew. While the story and history of Mashhads Jadid-al-Islam (new-converts) has been told on various occasions by previous scholars, Nissimis book takes on the task of theorizing the available data with the aim better to understand many of the prevalent present-day dynamics that define this particular segment of the Judeo-Persian family. With the aid of existing scholarship on other communities of forced-converts in the world such as the Conversos in Spain and Portugal, Nissimi explores previously unexamined issues regarding the lives of Mashhads forced-converts after the infamous Allahdad, and successfully brings to light many defining characteristics of todays Mashhadi communities in New York, Israel, and elsewhere. More specifically, she explores the prevalence of endogamy, the tight-knit socioeconomic bonds, and the often enviable social infrastructure that has succeeded in holding the community together across economic and geographic boundaries over 150 years since the experience of its collective trauma on 26 March 1839 back in Mashhad.

Chief among the themes Nissimi explores is the role of women in the Mashhadi community, both during and after the underground period. With convincing arguments, Nissimi underlines the role of women within the family structure as one of the central elements in promoting not only the fortification of social bonds within the community of forced-converts, but further of assuring the safekeeping of their hidden Jewish identity. In her theorization, Nissimi puts her finger on a particular dynamic that extends well beyond the set perimeters of Mashhads Jewish community into other Jewish communities throughout Iran. The dynamic in question pertains more generally to the larger issue of various Judeo-Persian languages that all find their roots in ancient Persian languages spoken in Iran before the arrival of Islam ca. 650 CE . Restricted to their homes by various norms and values of the IranianIslamic patriarchal society, women remained infinitely more sheltered from outside social influences than did their sons and husbands. In this, Jewish women, who were even further sheltered from Islamic culture and Arabic influences on the Persian language, thus passed on to their children a language that remained much closer to ancient Persian languages than modern-day Persian. A direct testimony to the strength of this dynamic is the fact that with the gradual social freedoms granted to women after the rise of the Pahlavi dynasty we can observe a directly proportional decline in the number of Iranian Jews who speak these languages. As women left their home to join the workforce and the social world outside, they left behind the knowledge and the need to pass on to their children the language they themselves had learned from their mothers before them. Today in 2006, it is near impossible to find anyone under the age of 60 who can converse with any degree of fluency in any one of these slowly dying Judeo-Persian languages. With pinpoint accuracy, Nissimi thus uncovers within the Mashhadi microcosm one of the central dynamics of Persian Jewry pertaining to the role of women as safekeepers of some of the characteristic elements of Jewish identity within the Iranian macrocosm.

Of equal importance is Nissimis extensive focus on the Mashhadi Jewish communitys excessive preoccupation with memory a dynamic I have elsewhere referred to as the anxiety of remembrance. Any scholar of Jewish Iranian history will quickly reach an inevitable point of frustration with the lack of factual stories and historical documents pertaining to the lives of Iranian Jews. Whether one chooses to theorize about this absence as a consequence of centuries of oppression and routine persecution during which much of the Jews homes, lives, and livelihoods were routinely looted and destroyed, or whether one tries to explain this lack of documentation as a requisite means of dissimulation to which Iranian Jews often reverted at times of perceived harm or actual threat, the fact remains that barring a few works such as Babai ben Lotfs Ketab-e anusim (The Book of Forced Converts) (17th century) and Babai ben Farhads Ketab-e sargozasht-e kashan dar babe-e ebri va guyimi-ye sani (The Book of Events in Kashan Concerning the Jews: Their Second Conversion) (18th century) little has survived of the history of Jews in Iran between the beginning of the sixteenth and the middle of the nineteenth centuries. Against the background of this disconcerting void, the body of memorabilia, written history, and collected oral stories about the underground lives of Mashhads forced-converts emerges as a veritable wealth of information, both chilling in its testimony and striking in its breadth. Correctly understanding the compulsory collection of these elements as symptomatic of a traumatized communitys compulsion not to forget, Nissimi explores in great detail various echoes of this anxiety of remembrance to explain some of the ways in which it has effectively functioned as a glue in an increasingly cohesive and tight-knit collective. Putting forth the convincing hypothesis that this anxiety has perpetually remained one of, if not the central factor in the perpetuation of endogamy within the Mashhadi community even now nearly four generations after the end of the anusim s underground years, Nissimi brings a new perspective and novel understanding to this characteristic feature of the present-day communitys continued closeness and tight social ties.