COMMUNAL SOLIDARITY

STUDIES IN IMMIGRATION AND CULTURE

ISSN 1914-1459

ROYDEN LOEWEN, SERIES EDITOR

16 Communal Solidarity: Immigration, Settlement, and Social Welfare in Winnipegs Jewish Community, 18821930, by Arthur Ross

15 Czech Refugees in Cold War Canada: 19451989, by Jan Raska

14 Holocaust Survivors in Canada: Exclusion, Inclusion, Transformation, 19471955, by Adara Goldberg

13 Transnational Radicals: Italian Anarchists in Canada and the U.S., 19151940 by Travis Tomchuk

12 Invisible Immigrants: The English in Canada since 1945, by Marilyn Barber and Murray Watson

11 The Showman and the Ukrainian Cause: Folk Dance, Film, and the Life of Vasile Avramenko, by Orest T. Martynowych

10 Young, Well-Educated, and Adaptable: Chilean Exiles in Ontario and Quebec, 19732010, by Francis Peddie

9 The Search for a Socialist El Dorado: Finnish Immigration to Soviet Karelia from the United States and Canada in the 1930s, by Alexey Golubev and Irina Takala

8 Rewriting the Break Event: Mennonites and Migration in Canadian Literature, by Robert Zacharias

7 Ethnic Elites and Canadian Identity: Japanese, Ukrainians, and Scots, 19191971, by Aya Fujiwara

6 Community and Frontier: A Ukrainian Settlement in the Canadian Parkland, by John C. Lehr

5 Storied Landscapes: Ethno-Religious Identity and the Canadian Prairies, by Frances Swyripa

4 Families, Lovers, and Their Letters: Italian Postwar Migration to Canada, by Sonia Cancian

3 Sounds of Ethnicity: Listening to German North America, 18501914, by Barbara Lorenzkowski

2 Mennonite Women in Canada: A History, by Marlene Epp

1 Imagined Homes: Soviet German Immigrants in Two Cities, by Hans Werner

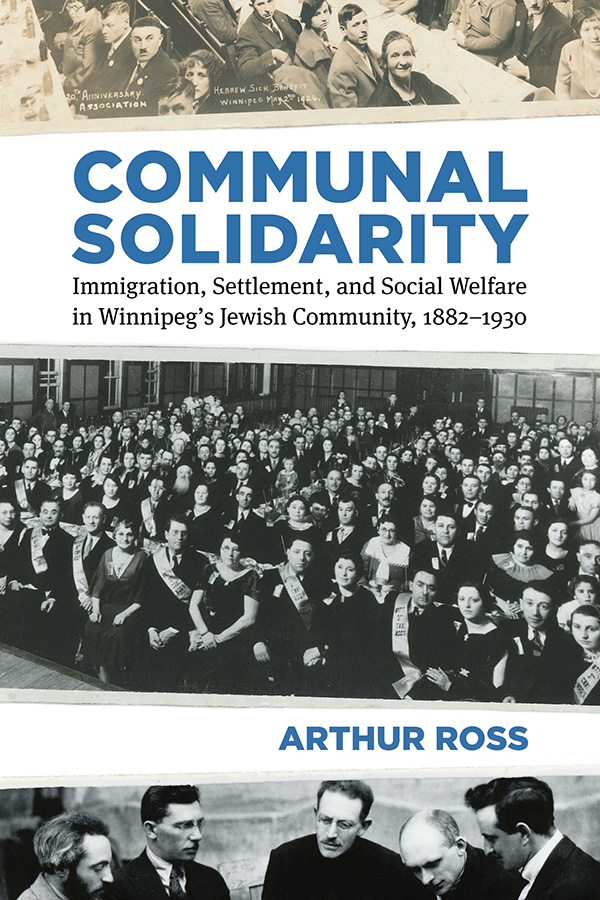

COMMUNAL SOLIDARITY

Immigration, Settlement, and Social Welfare in Winnipeg's Jewish Community, 18821930

ARTHUR ROSS

Communal Solidarity: Immigration, Settlement, and Social Welfare in Winnipegs Jewish Community, 18821930

Arthur Ross 2019

23 22 21 20 19 1 2 3 4 5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database and retrieval system in Canada, without the prior written permission of the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or any other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, www.accesscopyright.ca, 1-800-893-5777.

University of Manitoba Press

Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Treaty 1 Territory

uofmpress.ca

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

Studies in Immigration and Culture, ISSN 1914-1459; 16

ISBN 978-0-88755-837-5 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-88755-577-0 (pdf)

ISBN 978-0-88755-575-6 (epub)

Cover images: Courtesy of Author

Cover design John van der Woude

Interior design by Karen Armstrong

Printed in Canada

The University of Manitoba Press acknowledges the financial support for its publication program provided by the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Manitoba Department of Sport, Culture, and Heritage, the Manitoba Arts Council, and the Manitoba Book Publishing Tax Credit.

To Kathy

Contents

INTRODUCTION

Between 1882 and 1914, approximately 7,300 Jewish immigrants from the Pale of Settlement in Tsarist Russia settled in Winnipeg. Their decision to travel across an unfamiliar continent, embark on a difficult and lengthy transatlantic journey, and finally make their way to an unknown city thousands of kilometres from their port of entry was motivated by harsh necessity. Fleeing destitution, state persecution, and sporadic but increasingly murderous pogroms, emigration was a calculated risk. However, the estimated 2 million Jews who left the Pale of Settlement for the United States or Canada between 1882 and 1914 understood that, if they remained in Tsarist Russia, they had little prospect of improving their lives and would continue to endure unremitting hardship. They also knew that the traditional leaders of Jewish communities in the Pale of Settlement were incapable of either protecting them from oppressive state policies or alleviating their poverty. For those who made the difficult decision to emigrate, hopelessness outweighed the uncertainties of migration. After they arrived in Winnipeg, their previous experiences shaped their settlement, the process of finding a means of earning a living, and their founding of new Jewish communal institutions in an alien urban society. Freed from the social, economic, and legal constraints that had impoverished them and thwarted their ambitions, they were determined to earn a living either by finding the same type of work or by reinventing themselves, embracing new skills or occupations to take advantage of the diverse employment and business opportunities offered by Winnipegs burgeoning market economy. Similarly, no longer bound by the constraints of traditional Jewish communal authority, having been exposed in Tsarist Russia to the diverse social and political manifestations of a growing debate on Jewish emancipation, they were predisposed to take advantage of Canadas liberal democratic freedoms to establish new forms of communal governance.

In Canadas Jews: A Peoples Journey, Gerald Tulchinsky writes that the history of Canadian Jewish life contains elements of continuity and change.

The immigrants quickly discovered that, much like the shtetlekh, the small Jewish villages and towns that they had left behind, life in Winnipegs small Jewish community revolved around religious observance. By 1902, the community supported three synagogues. They provided Jewish immigrants not only with the comfort of a spiritual home, a place of worship where they could once again recite the familiar prayers and observe the religious holidays that had been an integral part of their communal life in the Pale of Settlement, but also membership in a congregation enabled them to make new friends and participate in social events such as weddings and celebrations of Jewish festivals such as Purim and Hanukkah. For the Jewish immigrants who established Winnipegs first synagogues, religious observance provided spiritual sustenance and an institutional base that enabled them to maintain their identities and adapt to an alien and often hostile society. In addition, as the only major institutions that had been established in the Jewish community, synagogues became forums for discussing communal affairs and safeguarding the welfare of its most vulnerable members. Throughout the early history of this community, synagogues provided an organizational platform to establish charities that dispensed assistance to destitute members of the community.

But reminiscent of the religious disputes that had disrupted Jewish communities throughout the Pale of Settlement, beginning in 1883 the synagogue congregations of Winnipegs Jewish community engaged in a series of bitter disagreements that divided the community, drained its financial resources, and undermined its capacity to raise money to protect its vulnerable members. As the leaders of the communitymen whose wealth enabled them to make substantial donations to synagogue building fundsorganized factions that competed with one another to promote the legitimacy of one form of religious observance at the expense of all others, their quarrelsome behaviour was an unwelcome reminder for many immigrants of how the rabbinate and men of wealth and privilege had dominated communal governance in the Pale of Settlement. Beginning in 1903, Jewish newcomers resolved to separate the provision of social welfare from religious adherence. Rejecting the prevailing synagogue-based practice of dispensing charity, a form of social welfare that divided members of the Jewish community into donors who made decisions about who was deserving and what they were entitled to receive and powerless supplicants who depended on their benevolence, these new immigrants began to establish mutual aid societies, organizations based upon egalitarian principles of communal solidarity. Implementing principles of self-help and reciprocal responsibility, mutual aid societies dealt with the pervasive problem of economic insecurity by providing financial benefits to their members free of the stigma of charity.