Studies in the History and Culture of the Middle East

Edited by

Stefan Heidemann

Gottfried Hagen

Andreas Kaplony

Rudi Matthee

Kristina L. Richardson

Volume

ISBN 9783110712872

e-ISBN (PDF) 9783110713619

e-ISBN (EPUB) 9783110713688

Despite careful production of our books, sometimes mistakes happen. Unfortunately, the series editor Kristina L. Richardson was misspelled in the original publication. This has been corrected. We apologize for the mistake.

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Introduction

Aims

The Compassionate and Benevolent is a monograph about the medieval Jewish community of the Mediterranean port city of Alexandria. In historical terms, it is a diachronic study, elucidating processes in a given socio-political arena over a defined period of time.

Alexandria as city or community, then, is not my subject here but rather the field of research through which I consider community relations and power dynamics in the medieval Jewish society of the Islamic lands. The nature of the Alexandrian Jewish community and the extent of its autonomy, both important topics in themselves, are not the focus of this book. My aim here is to present a well-defined micro-history and through it, to reveal some general truths as well.

In some instances, the book narrows its focus, attempting to provide a glimpse into the life stories, conducts and practises of contemporary private people. This is done in order to explore the intricate affiliations between individuals and groups and to better understand wider processes.

Our use of the term Islamicate rather than Islamic is crucial for this book. Coined by Marshall Hodgson in his seminal work The Venture of Islam (1974), the term Islamicate refers to the areas and societies ruled by Muslims, which may have included a Muslim majority, but that also included other significant non-hegemonic communities, who were full participants in the social, economic, cultural and intellectual activity and discourse of their time and space, in spite of their apparent second-class status (protected peoples, ahl al-dhimma). The term Islamicate represents the important truth that, alongside their idiosyncratic characteristics, all of these communities, Muslims, Jews and Christians, shared many cultural traits.

The Jewish community of Alexandria was an indispensable component of this medieval city. As such, its past does not constitute only part of Jewish history, but also reflects patterns and processes in medieval Islamicate society and culture.

Why Alexandria?

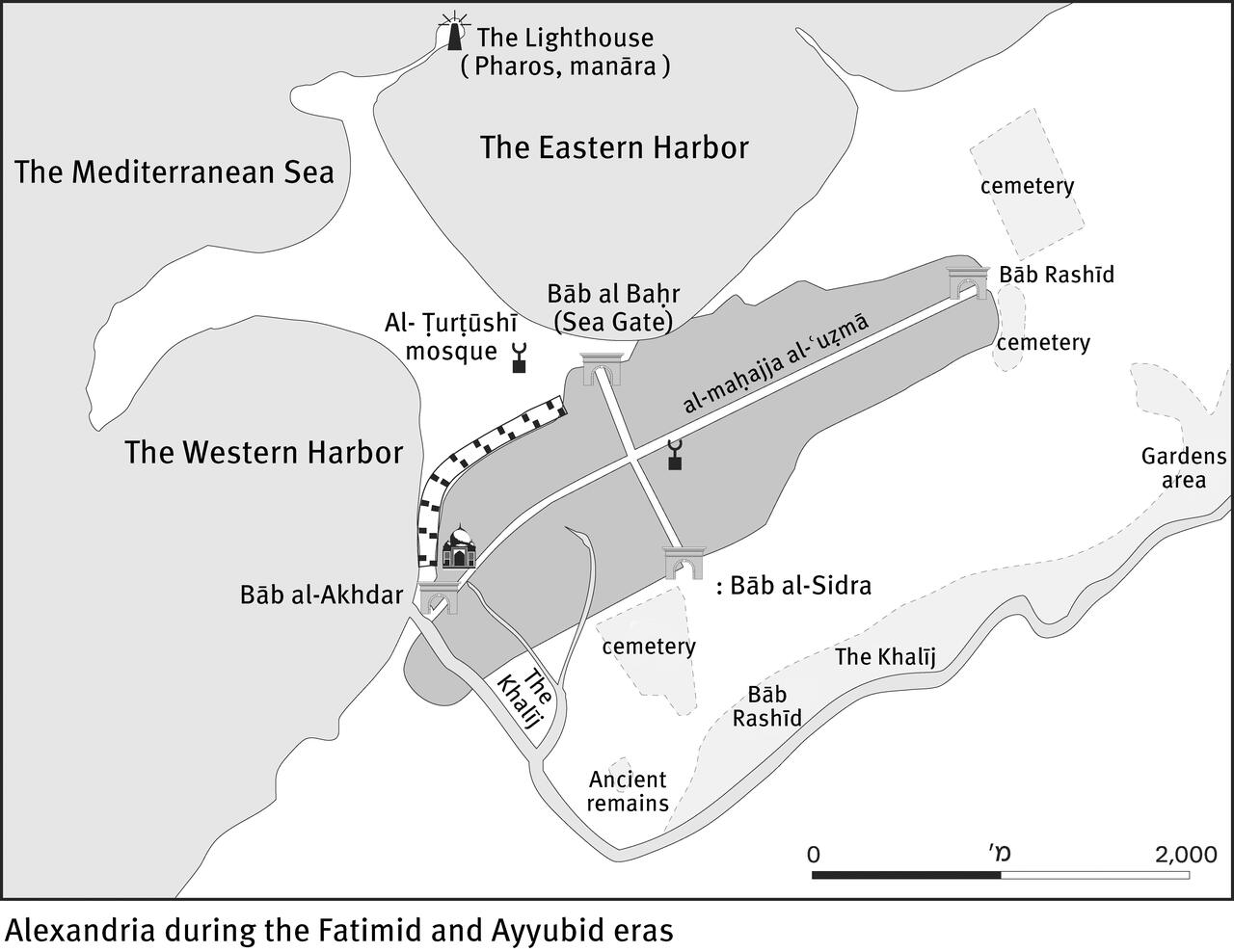

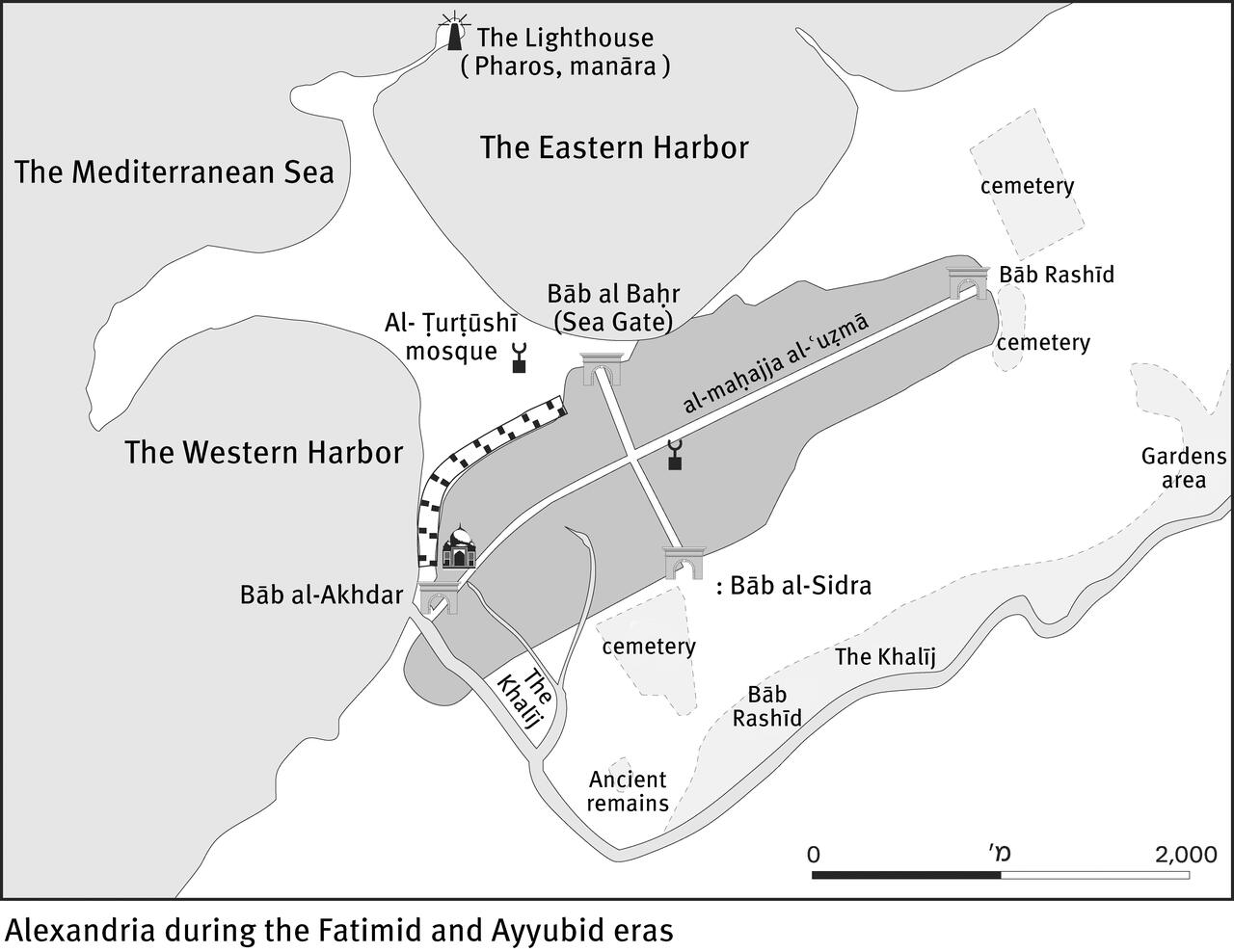

The city of Alexandria is a fertile field for research on Jewish leadership. In the first place, Alexandria with its urban setting was a primary scene of activity under Islam. To a large extent the urban spirit dictated the character of the realm and its politics. Alexandria, on the other hand, was a big enough city to provide the broad canvas needed for painting a clear and faithful portrait.

The Ruling Elite

Being ethnic and religious minorities, Jewish communities are frequently treated as monolithic entities, whose cohesive solidarity is highlighted and applauded. Nevertheless, the available sources, mainly those which originate from the Cairo Genizah, present themselves as voicing primarily a distinct segment within the Jewish community, that of its ruling elite.

The existence of elites that have a great deal of power and that act in a concerted fashion to preserve their status and continuity, aroused the interest of historians and social scientists already in the nineteenth century. Max Weber (18641920) connected the phenomenon to the increasing professionalization of modern society and to the rise of a professional bureaucracy,

It seems that after the first two decades of the postwar period, interest in elites faded as most attention was given to new social parameters such as gender, ethnicity, and later on to post-colonial issues. A certain revival of the topic is partially connected to the influential works by Pierre Bourdieu (19302002). Bourdieu paid much attention to matters of power and to the ways inequality is achieved, preserved, and reproduced through elite tastes, associations, and dispositions. The new notions he introduced to the field, such as cultural capital, habitus, and symbolic power, undermined earlier notions about the natural and necessary role of elites and provided new paradigms for the study of inequality.

The twenty-first century witnessed a revival of elite studies, most of them concerning the new elites in the United States

In the context of the present book, it may be worthwhile to mention also the work by E. Digby Baltzell (19151996) about the American elites, in which he provides detailed descriptions of the elites human composition, ways of life, careers, and ethics. In this informative and descriptive way, Baltzell brings these groups to light, delineates their boundaries and defines their nature. In my book I tried to follow a similar path, that is, to point out the very existence of such groups within Jewish society. Given the sweeping tendency to identify whole societies with their elite groups, especially in studies on Jewish history, I believe that even before trying to listen to the muted voices of the social margins: minorities, the poor, women, or children, it is worthwhile to put effort into exposing the elites and the ways they functioned.

Another source of inspiration for this book were the works by anthropologist Abner Cohen, who, by analyzing a variety of elites, has shown how elites that cannot organize themselves in an open and official manner manipulatively use the symbolic language of the society of which they are a part such as values, myths and rituals in order to solve their organizational problems.

Most of these studies were written in the social sciences. Hardly any historical studies have attempted to apply these rich theoretical frameworks to past societies. The elite group described in this book had its own particular political and economic interests, protected by an entire organizational system which aimed at securing its specific interests and at preserving its cohesiveness. The links which connected the various elite members were based on personal ties and were articulated in unofficial terms of friendship, love and kindness. The compassionate and benevolent are only part of the many titles with which members of the group used to address each other. The existence of this ruling elite group was never formally articulated, yet the implicit rules that dictated the nature of the informal political games played out in Jewish communities, as well as its patterns of leadership, seem both stable and steady. The leadership assumed the form of a wide network. The more connected a person was to others, and the more central his position in the network, the better his chances of acquiring a leadership position. The network comprised social, familial, economic, intellectual and commercial ties. It crossed geographical and communal boundaries and incorporated a steady pool of cosmopolitan members, who served as communal leaders at different stages of their lives in various places all over the Islamic world. Despite its wide geographical dispersion, this was a distinct and particular group, struggling simultaneously for its own interests as a group and for those of the wider Jewish society. All members of the ruling elite were engaged to some extent in commerce, and commercial links were an indispensable part of the networks connections, but not the sole ones. The network was made up out of very small circles, sometimes of no more than two merchants, but each merchant belonged to more than one circle and was thus able to serve as a link to several other circles. Each member actually stood at the center of a cluster of entangled circles, which all together constituted a ramified social and commercial network. The network covered a vast geographical range, from North Africa to India, and large quantities of merchandise and money circulated through it. The maintenance of the network was crucial to the continuance of this commercial machine and therefore commercial interests frequently overrode political, communal and religious conflicts. Members of opposing political fractions maintained their commercial relations even during seemingly dramatic disputes between Babylonians and Palestinians, Rabbanites and Karaites, locals and immigrants.