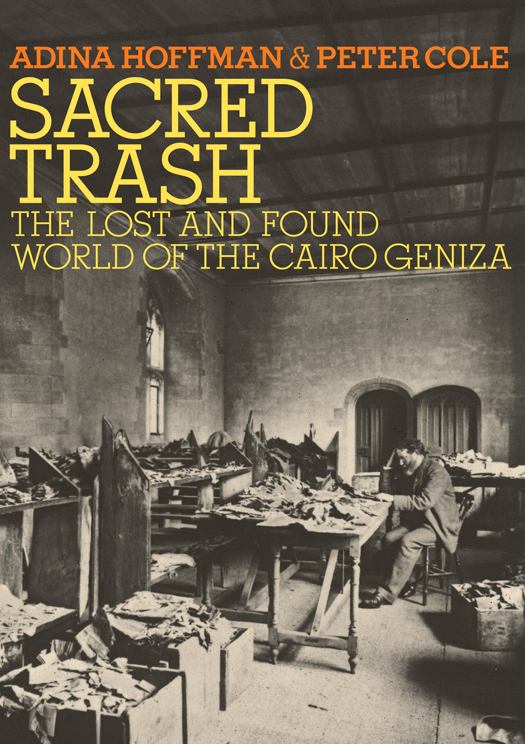

Copyright 2011 by Adina Hoffman and Peter Cole

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Schocken Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Schocken Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hoffman, Adina.

Sacred trash : the lost and found world of the Cairo Geniza / Adina Hoffman and Peter Cole.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-0-8052-4290-4

1. JudaismHistoryMedieval and early modern period, 4251789Sources. 2. JewsHistory701789Sources. 3. Cairo Genizah. I. Cole, Peter. II. Schechter, S. (Solomon), 18471915. III. Title.

BM 180. H 64 2010

296.0918220902dc22 2010016751

Jacket photograph reproduced by permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library

Jacket design by Barbara de Wilde

www.schocken.com

v3.1

JEWISH ENCOUNTERS

Jonathan Rosen, General Editor

Jewish Encounters is a collaboration between Schocken and Nextbook, a project devoted to the promotion of Jewish literature, culture, and ideas.

PUBLISHED

THE LIFE OF DAVID Robert Pinsky

MAIMONIDES Sherwin B. Nuland

BARNEY ROSS Douglas Century

BETRAYING SPINOZA Rebecca Goldstein

EMMA LAZARUS Esther Schor

THE WICKED SON David Mamet

MARC CHAGALL Jonathan Wilson

JEWS AND POWER Ruth R. Wisse

BENJAMIN DISRAELI Adam Kirsch

RESURRECTING HEBREW Ilan Stavans

THE JEWISH BODY Melvin Konner

RASHI Elie Wiesel

A FINE ROMANCE David Lehman

YEHUDA HALEVI Hillel Halkin

HILLEL Joseph Telushkin

BURNT BOOKS Rodger Kamenetz

THE EICHMANN TRIAL Deborah E. Lipstadt

SACRED TRASH Adina Hoffman and Peter Cole

FORTHCOMING

THE WORLDS OF SHOLOM ALEICHEM Jeremy Dauber

ABRAHAM Alan M. Dershowitz

MOSES Stephen J. Dubner

BIROBIJAN Masha Gessen

JUDAH MACCABEE Jeffrey Goldberg

THE DAIRY RESTAURANT Ben Katchor

JOB Rabbi Harold S. Kushner

ABRAHAM CAHAN Seth Lipsky

SHOW OF SHOWS David Margolick

MRS. FREUD Daphne Merkin

DAVID BEN-GURION Shimon Peres and David Landau

WHEN GRANT EXPELLED THE JEWS Jonathan Sarna

MESSIANISM Leon Wieseltier

For MMHC,

our Genizas sphinx

Hidden wisdom and concealed treasure, what is the use of either?

BEN SIRA

1

Hidden Wisdom

Cambridge, May 1896

W hen the self-taught Scottish scholar of Arabic and Syriac Agnes Lewis and her no-less-learned twin sister, Margaret Gibson, hurried down a street or a hallway, they movedas a friend later described themlike ships in full sail. Their plump frames, thick lips, and slightly hawkish eyes made them, theoretically, identical. And both were rather vain about their dainty hands, which on special occasions they weighed down with antique rings. In a poignant and peculiar coincidence, each of the sisters had been widowed after just a few years of happy marriage to a clergyman.

But Mrs. Lewis and Mrs. Gibson were distinct to those who knew them. Older by an entire twenty minutes, Agnes was the more ambitious, colorful, and domineering of the two; Margaret had a quieter intelligence and was, it was said, more normal. By age fifty, Agnes had written three travel books and three novels, and had translated a tourist guide from the Greek; Margaret had contributed amply to and probably helped write her sisters nonfiction books, edited her husbands translation of Cervantes Journey to Parnassus, and grown adept at watercolors. They were, meanwhile, exceptionally closearound Cambridge they came to be known as a single unit, the Giblewsand after the deaths of their husbands they devoted themselves and their sizable inheritance to a life of travel and study together.

This followed quite naturally from the maverick manner in which theyd been raised in a small town near Glasgow by their forward-thinking lawyer father, a widower, who subscribed to an educational philosophy that was equal parts Bohemian and Calvinistas far-out as it was firm. Eschewing the fashion for treating girls minds like fine china, he assumed his daughters were made of tougher stuff and schooled them as though they were sons, teaching them to think for themselves, to argue and ride horses. Perhaps most important, he had instilled in them early on a passion for philology, promising them that they could travel to any country on condition that they first learned its language. French, Spanish, German, and Italian followed, as did childhood trips around the Continent. He also encouraged the girls nearly familial friendship with their churchs progressive and intellectually daring young preacher, who had once been a protg of the opium-eating Romantic essayist Thomas de Quincy.

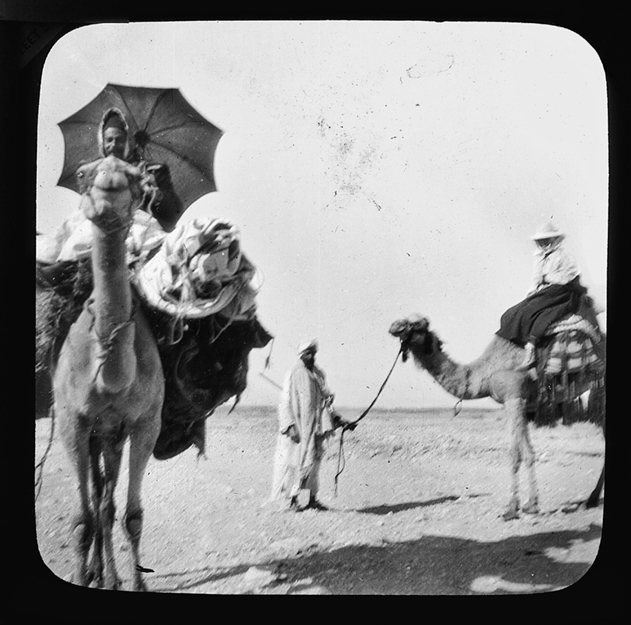

After their fathers sudden death when they were twenty-three, Agnes and Margaret sought consolation in strange alphabets and in travel to still more distant climes: Egypt, Palestine, Greece, and Cyprus. By middle age they had learned, between them, some nine languagesadding to their European repertoire Hebrew, Persian, and Syriac written in Estrangelo script. Having also studied the latest photographic techniques, they journeyed extensively throughout the East, taking thousands of pictures of ancient manuscript pages and buying piles of others, the most interesting of which they then set out to transcribe and translate.

()

As women, and as devout (not to mention eccentric and notoriously party-throwing) Presbyterians, they lived and worked on the margins of mostly Anglican, male-centered Cambridge societywomen were not granted degrees at the towns illustrious university until 1948and they counted as their closest friends a whole host of Quakers, freethinkers, and Jews. Yet Agness 1892 discovery at St. Catherines Monastery in Sinai of one of the oldest Syriac versions of the New Testament had brought the sisters respect in learned circles: their multiple books on the subject ranged from the strictly scholarly A Translation of the Four Gospels from the Syriac of the Sinai Palimpsest to the more talky and popular How the Codex Was Found. Somehow the rumor spread that Mrs. Lewis had just happened to recognize a fragment of the ancient manuscript in the monastery dining hall, where it was being used as a butter dish. In fact, the codex was kept under tight lock and key, and its very fragile conditionto say nothing of its sacred statuscertainly precluded its use by the monks as mere tableware. It took serious erudition and diplomacy for the twins to gain access to the manuscript in the monastery library; they then worked painstakingly over a period of years to decode the codex, as it were. The leaves, wrote Agnes, are deeply stained, and in parts ready to crumble. One and all of them were glued together, until the librarian of the Convent and I separated them with our fingers. She and Margaret proceeded to photograph each of its 358 pages and, on their return to Cambridge, processed the film themselves and labored over the texts decipherment. Later they arranged for an expedition of several distinguished Cambridge scholars to travel with them to Sinai, where they worked as a team, transcribing the codex as a whole.