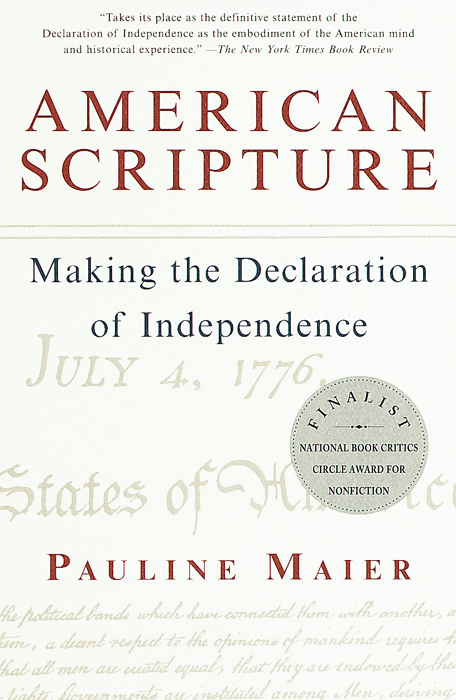

Acclaim for PAULINE MAIERs

American Scripture

American Scripture offers Americans a fresh perspective on their most treasured national relic.

The New York Times

A fascinating story. Maier has written a deft intellectual achievement.

Boston Globe

American Scripture is a timely reaffirmation that the Declaration of Independence is what Americans choose to make it. A remarkable, readable intellectual history.

USA Today

Maier has delivered a colorful study of our countrys most important political document: the Declaration of Independence.

The New York Post

Astute and accomplished. Carefully researched and thoughtfully written.

The New Republic

Outstanding. Employs superior historiography and political sensitivity to place the Declaration in its original context, and considers what it has become in the context of American political history.

Kirkus Reviews

ALSO BY PAULINE MAIER

From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 17561776

The Old Revolutionaries: Political Lives in the Age of Samuel Adams

The American People: A History

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, JULY 1998

Copyright 1997 by Pauline Maier

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, in 1997.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Knopf edition as follows:

Maier, Pauline.

American scripture: making the Declaration of Independence/Pauline Maier.

p. cm.

1. United States. Declaration of Independence.

2. United StatesPolitics and government1775-1783.

I. Title.

E221.M24 1997

973.313dc21 97-2769

CIP

eISBN: 978-0-307-79195-5

Author photograph Inspired Images

Random House Web address: www.randomhouse.com

v3.1

For Charles,

my Jeffersonian

Contents

Introduction:

Gathering at the Shrine

FEBRUARY 14, 1995. Speck-by-Speck, said the headline, the Nations Vital Documents Get Checkups. After years of preparation, the

A senior conservator carefully moved a fiber-optic light source over the surface of the Declaration, noting evidence of old bends and of earlier, amateurish repairs. She also took photographs of the document with a 35-millimeter camera, then placed sheets of plastic film over the case and traced the locations of tears, bends, repairs, glue spots, even scars from the animal skins used to make the parchment, confident that her painstaking work would produce invaluable information. Meanwhile, a physicist and, I assume, other conservators examined the Bill of Rights with a computerized imaging system capable of discovering the disappearance, or even the fading, of the tiniest flakes of eighteenth-century black, iron-based ink, which, it turns out, fades to brown with age, particularly if exposed to light. (That was news to me. For decades Ive read handwritten eighteenth-century documents assuming that brown ink was the style of the time. Even the colors of the past, it seems, can no longer be observed directly.)

The computerized imaging system, the jewel in the crown of the Archives conservation program, was developed after 1981, when experts suggested that new and better ways be found than those then available to monitor the documents condition. The Archives turned for help to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, which, in turn, had engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, design a system for taking precise pictures of the documents that was based in part on equipment being created for the Hubble Space Telescope. The

The discovery of haze where the Bill of Rights had touched glass prompted consultations with a microbiologist and a glass chemist. The problem seemed worse than when the document was examined in 1988, perhaps because the fiber-optic light source was more sensitive than the incandescent bulb used in the earlier examination. Or was there a real physical change, and, if so, was it caused by some chemical reaction between the parchment and glass or by a living organism capable of surviving without oxygen? The 1995 evaluation confirmed earlier observations of tiny white flakes in the document enclosures that could be sodium coming from the glass or perhaps the result of other structural changes in the glass. All these phenomena were noted, measured, evaluated, and recorded for future reference.

The Continental Congress probably hauled the documentrolled up, as was the custom with parchment scrollswith its other papers as it moved from place to place in the course of the revolutionary war. Later the Declaration found resting places with the national government at New York, Philadelphia, and, in 1800, at the nations new capital in Washington, D.C. The Department of State received custody when the Declaration of Independence was still a teenager, but even so it was continually transferred from building to building, or from home to home. When the British invaded in August 1814, a government clerk managed to save the document from destruction. By the time it returned to Washington from its hiding place in Leesburg, Virginia, curiosity seekers found its text, and particularly the signatures, which were written in various qualities of ink, already in bad shape. The wet-pressing process used to make a facsimile in 1823 did further damage, and the fading continued after 1841 when the State Department grew tired of pulling the document out to show visitors and put it on public display for the first timeon a wall in the new Patent Office opposite a large window, where it remained for thirty-five years. The document traveled to Philadelphias Independence Hall for six months during the centennial celebrations of 1876, and was subsequently put on display in the State Departments library.

By its hundredth year, however, the Declarations decay had become so obvious that the first of many scientific committees was appointed to decide what to do. Generally the experts recommended keeping the document out of light and, in 1903, as dry as possible, but their advice was not always followed. That was perhaps just as well, since extreme dryness makes parchment crack. Custodians continually sought to protect the document from fire, but no other serious efforts at preservation were made until the State Department transferred the

Enormous care was taken to preserve the documents. They were covered with double panes of plate glass between which a gelatin film filtered damaging light rays, and a continuous guard kept watch for thieves and other evil-minded people as well as for the silverfish someone reported seeing in the Constitutions case, causing near-panic.National Archives.

Modern scientific document conservation is obviously a very recent development, and it has not advanced equally on all fronts. Our ability to detect problems is growing faster than our ability to solve them, according to a professor of conservation associated with the monitoring program. What to do if we find something becomes the more difficult question. And an important one, it seems. The original, signed texts of the Declaration of Independence and, to a lesser extent, the Constitution have become for the United States what Lenins body was for the Soviet Union, a tangible remnant of the revolution to which its children can still cling. What we are struggling to preserve from time is, however, not a physical body but a physical document that was written to perform a constitutional function. That, too, involves some irony. The heroic efforts invested in conserving the document by which the United States declared its Independence from Britain testify to the powerful and enduring influence of English constitutional tradition on American political culture.