Contents

Guide

This project was funded in part by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. government.

The publishers wish to thank The Blue Family Charitable Fund and The Kagawa Family Charitable Fund, as well as individual donors, for their generous support of this project.

2018 by Manzanar History Association

All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from Heyday.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

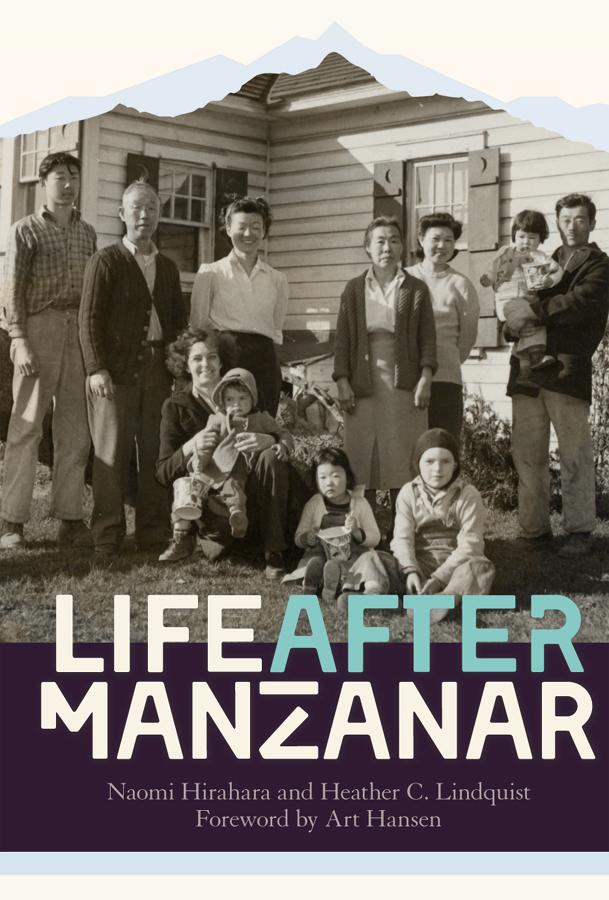

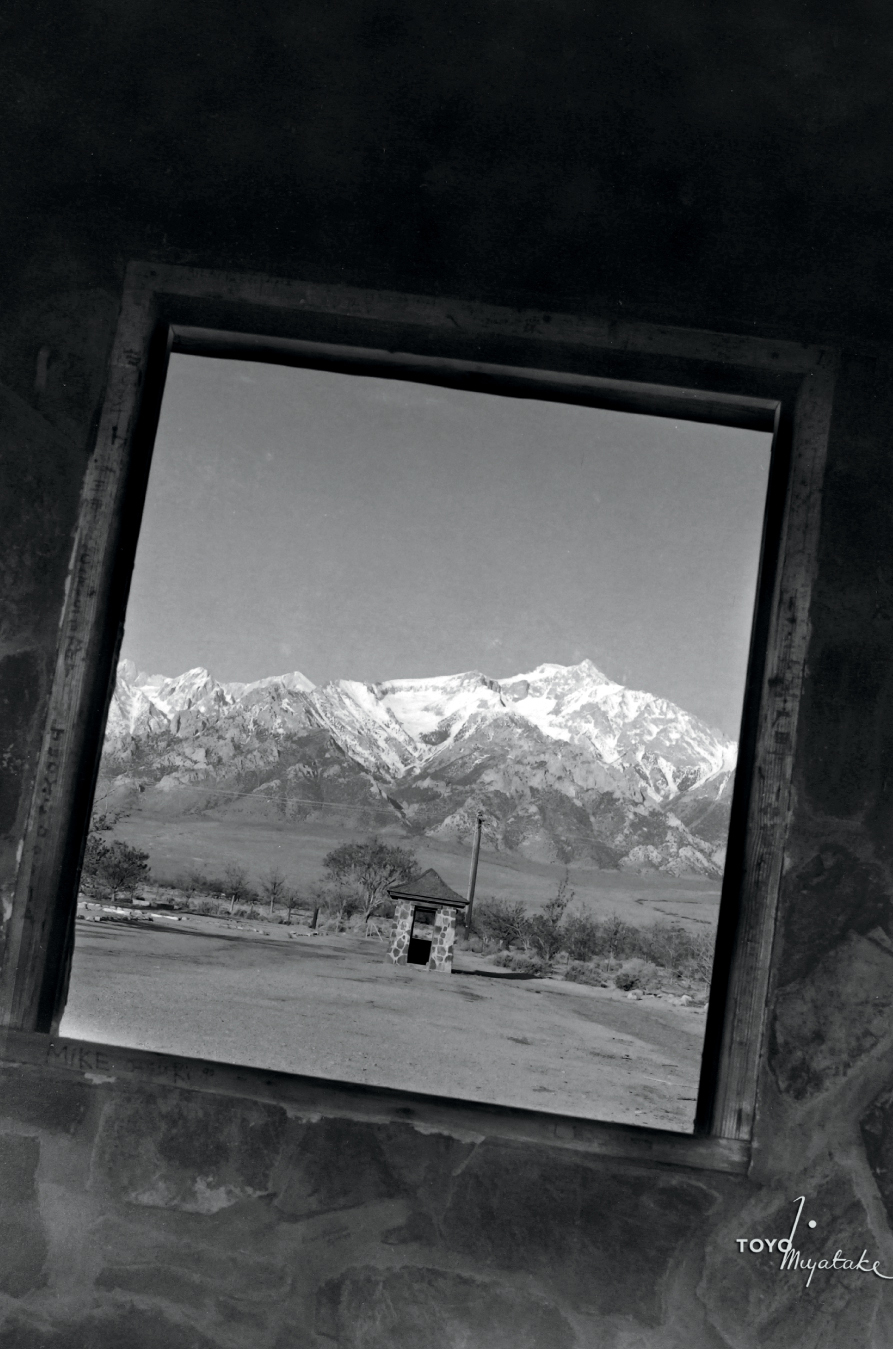

Cover photo by Stone Ishimaru. Courtesy of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. Tec Com Productions

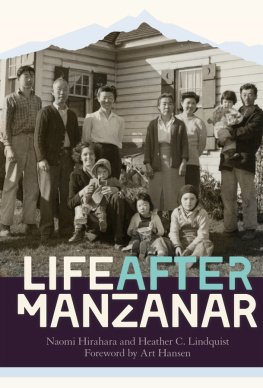

The family of Ichisuke and Ume Fukuhara, originally from Santa Monica, California, left Manzanar War Relocation Center and temporarily resettled in Farmingdale, Long Island. Here they are posed with their new friends, the Olsen family, outside their house on the grounds of the Calderone Greenhouses. Standing (left to right) are son Willy, Ichisuke, daughter Tomiko, Ume, daughter-in-law Fujiko, and Henry Fukuhara, Fujikos husband, who is holding their younger daughter, Yoshino. Among those seated is their older daughter, Shizuko.

ISBN: 9781597144469

Book design by Rebecca LeGates

Orders, inquiries, and correspondence should be addressed to:

Heyday

P.O. Box 9145, Berkeley, CA 94709

(510) 549-3564, Fax (510) 549-1889

www.heydaybooks.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to Maggie Wittenburg, former executive director of Manzanar History Association, and Jim Howell, a former National Park Service park guide. Maggie began volunteering for Manzanar History Association in 2003, and over the years, she rose to the role of executive director. Jim began working as a seasonal ranger for Manzanar in 2010, followed by a stint at Tule Lake and a second season at Manzanar. Maggie recruited Jim to work as a researcher for this book, and he did so, refusing to accept pay. For both Maggie and Jim, this book was a labor of love, not only because of the important lessons it has to teach but for the opportunity it gave them to collaborate. They shared a passion for history and for preserving the stories and lessons of Manzanar, but, unfortunately, they also shared a journey neither could have imagined when this book project began. Both were diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in late 2016 and died within six weeks of each otherMaggie in December 2016 and Jim in January 2017. We wish they could be here to see the results of their vision and work. We were honored to work with them and believe they would be honored by the final product of their efforts.

Alisa Lynch, chief of interpretation, Manzanar National Historic Site, National Park Service

Bob Takamoto, Bruce Sansui, and Mas Ooka revisit Manzanar, July 2016. Right: Bob, Bruce, and Mas as boys, growing up behind barbed wire, c. 1944.

In 1942, the United States government ordered more than 110,000 men, women, and children to leave their homes and detained them in remote, military-style camps. Two-thirds of them were born in America. Not one was convicted of espionage or sabotage. Introductory text to the Visitor Center exhibition at Manzanar National Park

What becomes history and from whose point of view? How do you encourage people to explore its dark chapters and come away even stronger? Why remember when you would just as soon forget? Karen Ishizuka in Lost and Found: Reclaiming the Japanese American Incarceration

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Following Japans attack on the Pearl Harbor naval base in the United States territory of Hawaii on December 7, 1941, the U.S. government removed some 120,000 people of Japanese ancestryabout two-thirds of them American citizens, the remainder Japan-born aliens banned by law from achieving U.S. citizenshipfrom their homes on the West Coast and beyond, confining them in American-style concentration camps.

Historically, the World War II experience of people of Japanese descent (Nikkei) was referred to euphemistically as an evacuation or incorrectly as an internment. Recently, however, it has been characterized more realistically, if still too restrictively, as an incarceration. Perhaps, though, it would most accurately be designated a social disaster. Striking with as much force and devastation as some natural disasters, the wartime catastrophe that befell the Japanese Americans was entirely human-made, the result of racism, exploitation, improper government leadership, and lack of public vigil.

The U.S. governments stated rationale for the enforced mass uprooting and incarceration of Japanese Americans was military necessity and national security. Under the guise of keeping the nation safe from its enemies, Nikkei Americans were removed from their homes and communities and consigned for the duration of the war to remote and crude detention facilities located in windblown deserts and boggy forests of the countrys interior.

The first of these detention facilities was Manzanar, which made it the flagship and prototype for all the others that followed in its wake. It was located outside West Coast military zones in eastern Californias Inyo County, 212 miles north of Los Angeles and nearly halfway between the Owens Valley towns of Lone Pine and Independence, on U.S. Highway 395. Before the 1860s, the Manzanar site had been home for centuries to Paiute and Shoshone Indians. They were displaced by homesteaders, who in turn sold out to developer George Chaffey in the early 1900s. Chaffey planted fruit trees, subdivided the property into small ranches, and marketed it as Manzanar (Spanish for apple orchard). By 1930, the orchard owners had sold the land to the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power.

The Manzanar camp was established initially by the U.S. Army as an assembly center, and from March 21 through May 31, 1942, it was managed by the Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) as the Owens Valley Reception Center. On June 1, 1942, Manzanar became the only one of fifteen total assembly centers to be reconstituted as a relocation center administered by the War Relocation Authority (WRA), and it was renamed Manzanar War Relocation Center. As a WCCA unit, Manzanar had one project director (Clayton Triggs) and two acting directors (Solon Kimball and Harvey Coverley). In its relocation center phase, which extended to its shutdown on November 21, 1945, Manzanars two directors were Roy Nash (until November 24, 1942) and Ralph P. Merritt. The overwhelming majority of the camps peak population of 10,046 (nearly equally divided between male and female, with one-quarter of them school-age children) derived primarily from prewar Japanese American communities in Los Angeles County, particularly the city of Los Angeles, which was the prewar population, commercial, and sociocultural capital of mainland Japanese America.