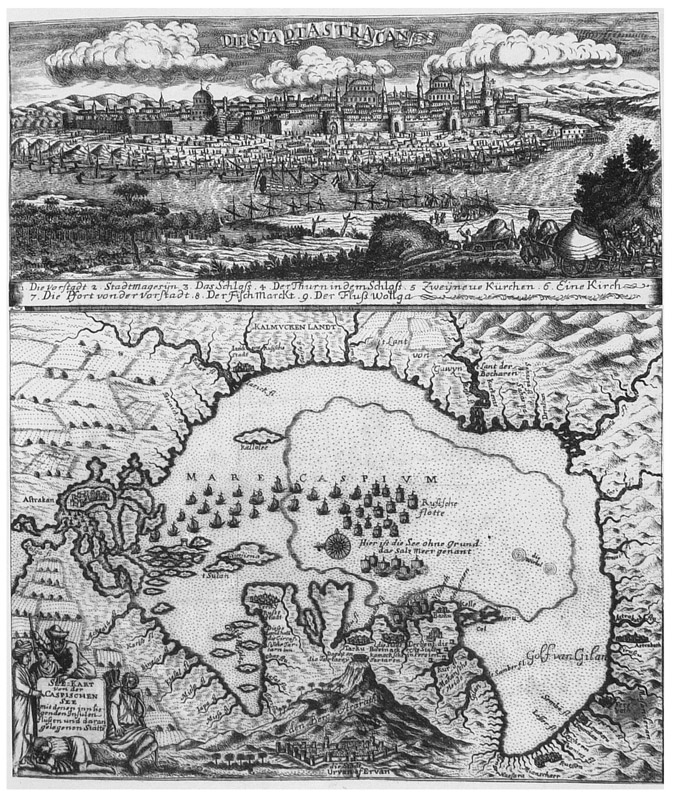

Vid Astrakhani i karta Kaspiiskogo moria (View of Astrakhan and the Caspian Sea) (1678), from the German edition of Jan Struyss Reisen durch Greichenland, Moscau, Tatarey... , reproduced in Natal'ia Borisovskaia, Starinnye gravirovannye karty i plany xvxviii vekov (Galaxy, Moscow, 1992), p. 155.

CHAPTER ONE

Frontier Colonization

As heaven and earth beget them, men have one same heaven, but each a different earth.

Ch'iu Chn, Supplement to the Expansion of the Great Learning

THE RUS' LAND AND THE FIELD

According to the Primary Chronicle, when the first Eastern Slavs established themselves in what would become Ukraine and western Russia they settled in woods and along waterways: So these Slavs came and settled on the Dniepr and called themselves People of the Clearings [poliane]; others called themselves People of the Trees [drevliane] because they settled in the forests; and different ones settled on the Dvina and called themselves People of the Polota [polochane], taking the name of the Polota River, which flows into the Dvina. And those Slavs who settled near Lake Ilmen' called themselves by their own nameSlavsand they built a town and called it Novgorod [New Town].

Known to the Rus' as the field (pole), the grassy plains that opened up to the south of their settlements appeared completely different. In contrast to the Rus' land (rus'kaia zemlia), the field contained few freshwater lakes or trees, and its inhabitants were nomadic pastoralists who did not speak Slavic, did not farm, had no permanent homes, and had little interest in either written law or the Christian god. Instead, as the chronicler put it, they lived according to the ways of their fathers, which included such unsavory habits as shedding blood, eating carrion and prairie dogs, and sleeping with their stepmothers.

The Rus' and the nomads were also tied through the Rus'-sponsored trade from the Varangians to the Greeks, which crossed the steppe and consequently depended on the nomads cooperation for its success.

Whenever the Rus' refused to provide the nomads with the gifts they expected, or the nomads broke their arrangements with the Rus' by raiding Rus' towns to seize slaves and other booty, the trade suffered, but such hostilities were rarely prolonged enough to shut the trade down completely.

The most obvious physical example of the complicated consequences of cohabitation was the stretches of earthen ramparts and palisades that the Rus' began building south of their settlements in the time of Vladimir the Great and Iaroslav the Wise. Known to subsequent Slavs as serpentine walls (zmievye valy), the intended purpose of the ramparts was to keep the nomads from raiding Rus' towns, as well as to keep the lands between the walls and the towns from being turned into nomadic pasture.

THE WILD FIELD AND THE TSARDOM

This rough parity collapsed in 1223 when the Rus' and their Polovtsy allies were routed by an army of unknown peoples (iazytsi neznaeme) on the steppe near the Kalka River.

This remained the case even after the armies of Ivan IV conquered the town of Kazan in 1552. Pragmatism in relations with the steppe continued, only now the presumption was that Moscow alone should be in charge. During the next four years, the men of Ivan Vasil'evich subju-gated the rest of Kazans territory, and in the summer of 1556, with the aid and encouragement of their allies among the Nogays, they seized the poorly defended entrepot of Astrakhan at the mouth of the Volga and chased out the independent Astrakhan tsar, replacing him with a Nogay khan obedient to Moscow.

Yet for all that, the Russian takeover of the mostly Islamic world of the Volga and trans-Volga steppes nonetheless marked a key turning point. In the second half of the sixteenth century, the eastern end of the field became part of the tsardom, and the tsardom itself took an important step toward becoming a colonial empire. But the colonial lands that the tsar was acquiring were, for obvious reasons, seen quite differently than those being colonized by other European states in the same period. Unlike their European peers, the Muscovites did not cross the Western Sea or any sea at all to obtain their possessions, and if the American continent rightly constituted a new world, as Amerigo Vespucci insisted, because the ancients had no knowledge of them,

Perhaps most importantly, the Muscovites were not given to exploring or describing their new grasslands because there was as yet no perceived need to do so. that the first Europeans encountered in the New World, for the simple reason that the steppe was not new and the Muscovites were not inclined toward describing. This was largely how things would stay until the eighteenth century.

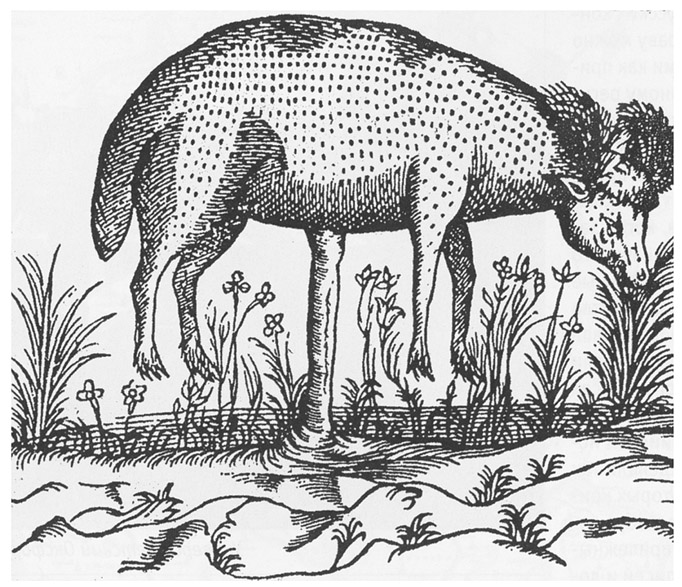

Engraving of the so-called baranets-melon, which appears to be from a seventeenth-century English manuscript. Rodina, 2003, n. 5/6, p. 24.

Yet if the Muscovites seem to have been somewhat short on ethno-graphic curiosity, their colonial inclinations were otherwise fully compar As one Bashkir clan leader recalled:

In the Year of the Mouse, on the second of October, the Russians took the city of Kazan and the White Prince [belyi-bii] became the sovereign [padishakh]. It was in [that year] that envoys went to all the lands with documents that said, Let no one run away, let all remain true to their faith and customs.... And I, Tatigach-bii, unable to think of anything else to do, summoned three men from the three clans of the people... and we traveled to Kazan where we agreed to be subjects of... the White Prince sovereign. We received the patent [iarlik], and gifts of food and satin cloth, and told the tsar that we are a people of three-hundred houses [i.e., nomadic tents] and that we have, after humbly requesting his permission, occupied the lands left behind by the Nogay. [The tsar] granted to us the landsfrom the upper White River, bordering on the Nugush, to the lower, bordering on the Kukush, with all the rivers and steppes, hills, and rocks that are on both banks. We then promised to pay tribute [iasak] in marten pelts, and after that, the White Prince ruler granted me, Tatigach-bii, the rank of noble.

Viewing fealty as a matter of quid pro quo, the nomads conducted themselves accordingly, alternatively cooperating with the Muscovites or raiding their settlements (or both), depending on what most suited their interests. The same Bashkirs who pledged their allegiance to Moscow in the 1550s, for example, were raiding Muscovite villages on the Kama just a few years later. Naturally, the tsars men were not impressed with this kind of inconstant behavior and built forts, took hostages, curried additional favors, and dispatched posses to try to stop it. Ill-equipped for the steppe in military terms, outnumbered, and isolated, there was not much they could do, however.

And the tsars men were indeed isolated. The Muscovite population of the garrison towns on the Volga and the monastery lands in the forest-steppe of Bashkiria numbered just a few thousand in the late sixteenth century.

Given their, at best, partial possession of the field, the rulers of Moscow naturally continued to defend themselves. During the troubles that affected the Horde in the fourteenth century, and then later following its unraveling in the mid-fifteenth, various Rus' princes resumed the old practice of building palisades and earthworks between stands of forest to cut off (