v

For Sue

vi

C ontents

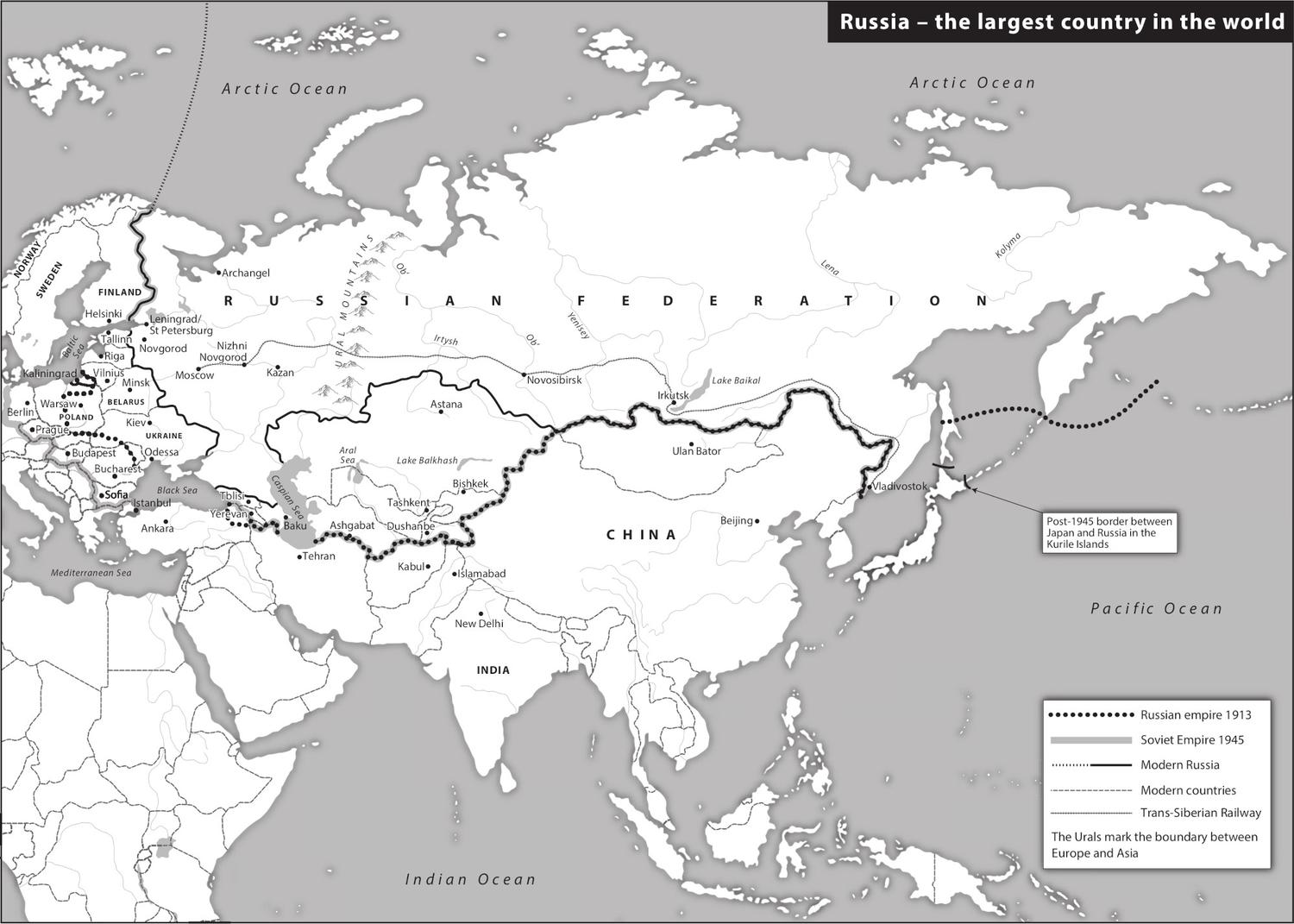

In writing about Russian history, you are faced by an immediate problem: what do you call the country you are writing about? It has been known as Rus, Muscovy, Russia, the Russian empire, the Soviet Union, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the Russian Republic. Not only Russians live in this country: at various times its inhabitants have included Ukrainians, Poles, Tartars, people from the Baltic, the Caucasus, Central Asia and many other places. Each name has political and historical overtones about which there is passionate disagreement among scholars, politicians, journalists and ordinary people.

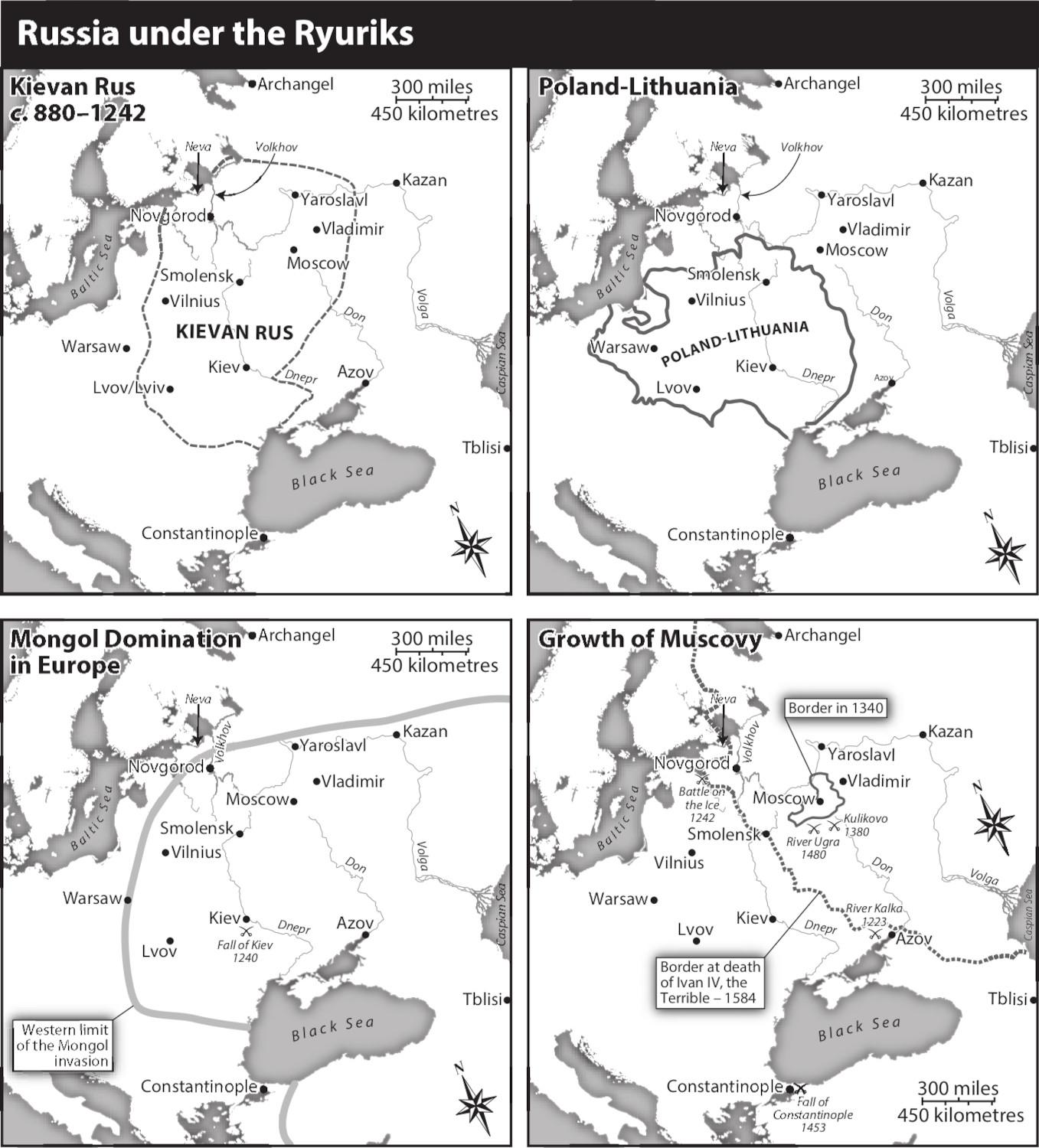

There is a particular problem about how to name the state based on the medieval city of Kiev. Most Russians call it Kievan Rus and believe that their modern state is its direct descendant. That is something that many Ukrainians vehemently deny. They call the city Kyiv, and insist on the Ukrainian spelling of other proper names too. I have tried to use whichever spelling seemed appropriate to the historical period. But many people will inevitably disagree with me.

Part of the book that follows is an attempt to explain why these differences are so important. I apologise for x nevertheless finding it simplest to use the words Russia, Russian and Kiev for much of the time.

*

In transcribing Russian words into English, I have deliberately avoided the standard scholarly systems. I have tried instead to make things as easy as may be for the non-Russian speaker (Russian speakers will be able to work out the original spelling for themselves).

The sounds should therefore be spoken as written. Sounds that do not exist in English are represented thus: kh, sounds like ch in loch; zh sounds like ge in rouge. An e at the beginning of a Russian word is usually pronounced ye. Thus Yeltsin, not Eltsin; but Mount Elbruz, not Mount Yelbruz (because in Russian the E in this case is a different letter). While is pronounced yo. Thus Fedor is pronounced Fyodor, and I so spell it and similar names such as Semen/Semyon. Khrushchev and Gorbachev are pronounced Khrushchyov and Gorbachyov, but I have chosen to stay with the more familiar spellings.

I use familiar English versions: Moscow, not Moskva; Peter, not Ptr; Alexander, not Aleksandr. But I depart from consistency when that feels best. So, for example, I prefer Mikhail to Michael.

People unfamiliar with them find Russian names very hard to remember. Its almost impossible to make it easier, but it may help occasionally if you remember that between the first name and the surname in Russian comes the patronymic, which ends in -ovich/-evich for a man xi and -ovna/-evna for a woman. One cant distinguish in English between two men both called John Johnson. But Ivan Ivanovich Ivanov is John Johnson son of John, and Ivan Stepanovich Ivanov is John Johnson son of Stephen. It is perfectly proper to refer to someone by his or her first name and patronymic. Thus the last President of the Soviet Union and the first two Presidents of the Russian Republic could be respectfully addressed as Mikhail Sergeevich, Boris Nikolaevich and Vladimir Vladimirovich.

I have spelled the last syllable of Russian names, where appropriate, as -sky. I have left Polish names ending in -ski, since that is how they are spelled in Polish.

This book is too short to support scholarly notes or a bibliography. I have, however, attributed direct quotations in endnotes. And I have added a very short and personal list of books.

xii

xiv

xv

xvi

Russia is a country with an unpredictable past.

Popular Russian saying

Everyone has a national narrative, constructed from fact, fact misremembered and myth. People tell themselves stories about their past to give some meaning to the confusions of their present. They rewrite their stories from generation to generation to adapt them to new realities. They omit, forget or wholly reinvent episodes that are uncomfortable or disgraceful.

These stories have deep roots. They feed our patriotism. They help us understand who we are, where we come from, where we belong. Our rulers believe them no less than we do. They hold us together in a Nation and inspire us to sacrifice our lives in its name.

The British have their Island Story of undeviating progress from Magna Carta towards power, freedom and democracy, punctuated by shining victories over the French: Winston Churchill wrote it up in his grandiloquent A History of the English-Speaking Peoples. The English acquired, exploited and then lost three empires in 600 years. The descendants of their imperial subjects think of them as greedy, brutal, devious and hypocritical. That is not at all how they think of themselves.

But the Nation is a slippery thing. Nations are like amoebas. They emerge from the depths of history. They wriggle around. They split by binary fission, recombine in different configurations, absorb their neighbours or are absorbed by them, and then disappear. War, politics, dynastic marriage, popular referendums shift provinces from one side of a frontier to the other. Ordinary people can be born in one country, grow up in another and die in a third, all without leaving their home town. Ask a Frenchman who was born in Alsace-Lorraine in 1869. Ask an Austrian Jew who was born on the border of Slovakia and Hungary in 1917. Ask a Pole who was born before the Second World War in what is now the Ukrainian city of Lviv, which since its foundation as Levhorod in the thirteenth century has been known to its Polish, Austrian, German and Russian rulers as Lww, Lemberg and Lvov.

Few of the states in todays Europe existed before the First World War. When Columbus discovered America, Germany, Italy, Russia and even France and Britain were still fragmented and the Polish-Lithuanian Union was on the way to becoming the largest state in Europe.

The idea of Europe is itself largely an artificial construction, an attempt to bring under one roof a collection of countries at the western end of the Euro-Asian land mass, each very different from the others, ranging from Iceland to Romania, from Norway to Greece, from Spain to Estonia, loosely bound together by a tradition of Christianity and a murderous record of domestic persecution, bloody rebellion and violent religious conflict at home, endless war for power and loot, genocide, slavery and imperial brutality abroad.

By those depressing standards Russians have as good a claim to be European as anyone else. Partly because of its huge extent eastwards into Asia, both Russians and foreigners nevertheless wonder whether Russia is part of Europe at all. Many of their immediate neighbours consider them Asiatic barbarians, and point angrily to the sufferings that the Russians have inflicted on them over the centuries. Napoleon was right, they think, when he allegedly said, Scratch a Russian and youll find a Tartar.

More than a thousand years ago a people arose on the territory of todays Russia whose origins are disputed. They adopted the Orthodox version of Christianity from Byzantium, thus irrevocably distinguishing themselves from those elsewhere in Europe who chose Roman Catholicism. They developed their own Slavonic language. They created Kievan Rus, which for a while was the largest and one of the most sophisticated, if also one of the most ramshackle, states in Europe. It is from here that todays Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians trace their origins.