Rodric Braithwaite - Russia: Myths and Realities

Here you can read online Rodric Braithwaite - Russia: Myths and Realities full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: Profile, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Russia: Myths and Realities

- Author:

- Publisher:Profile

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Russia: Myths and Realities: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Russia: Myths and Realities" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Russia: Myths and Realities — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Russia: Myths and Realities" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

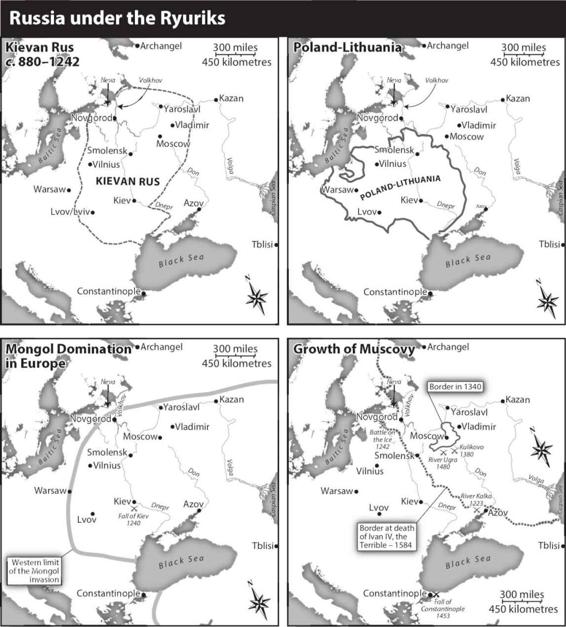

For Sue C ONTENTS In writing about Russian history, you are faced by an immediate problem: what do you call the country you are writing about? It has been known as Rus, Muscovy, Russia, the Russian empire, the Soviet Union, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the Russian Republic. Not only Russians live in this country: at various times its inhabitants have included Ukrainians, Poles, Tartars, people from the Baltic, the Caucasus, Central Asia and many other places. Each name has political and historical overtones about which there is passionate disagreement among scholars, politicians, journalists and ordinary people.There is a particular problem about how to name the state based on the medieval city of Kiev. Most Russians call it Kievan Rus and believe that their modern state is its direct descendant. That is something that many Ukrainians vehemently deny. They call the city Kyiv, and insist on the Ukrainian spelling of other proper names too. I have tried to use whichever spelling seemed appropriate to the historical period. But many people will inevitably disagree with me.Part of the book that follows is an attempt to explain why these differences are so important. I apologise for nevertheless finding it simplest to use the words Russia, Russian and Kiev for much of the time.*In transcribing Russian words into English, I have deliberately avoided the standard scholarly systems. I have tried instead to make things as easy as may be for the non-Russian speaker (Russian speakers will be able to work out the original spelling for themselves).The sounds should therefore be spoken as written. Sounds that do not exist in English are represented thus: kh, sounds like ch in loch; zh sounds like ge in rouge. An e at the beginning of a Russian word is usually pronounced ye. Thus Yeltsin, not Eltsin; but Mount Elbruz, not Mount Yelbruz (because in Russian the E in this case is a different letter). While is pronounced yo. Thus Fedor is pronounced Fyodor, and I so spell it and similar names such as Semen/Semyon. Khrushchev and Gorbachev are pronounced Khrushchyov and Gorbachyov, but I have chosen to stay with the more familiar spellings.I use familiar English versions: Moscow, not Moskva; Peter, not Ptr; Alexander, not Aleksandr. But I depart from consistency when that feels best. So, for example, I prefer Mikhail to Michael.People unfamiliar with them find Russian names very hard to remember. Its almost impossible to make it easier, but it may help occasionally if you remember that between the first name and the surname in Russian comes the patronymic, which ends in -ovich/-evich for a man and -ovna/-evna for a woman. One cant distinguish in English between two men both called John Johnson. But Ivan Ivanovich Ivanov is John Johnson son of John, and Ivan Stepanovich Ivanov is John Johnson son of Stephen. It is perfectly proper to refer to someone by his or her first name and patronymic. Thus the last President of the Soviet Union and the first two Presidents of the Russian Republic could be respectfully addressed as Mikhail Sergeevich, Boris Nikolaevich and Vladimir Vladimirovich.I have spelled the last syllable of Russian names, where appropriate, as -sky. I have left Polish names ending in -ski, since that is how they are spelled in Polish.This book is too short to support scholarly notes or a bibliography. I have, however, attributed direct quotations in endnotes. And I have added a very short and personal list of books.

For Sue C ONTENTS In writing about Russian history, you are faced by an immediate problem: what do you call the country you are writing about? It has been known as Rus, Muscovy, Russia, the Russian empire, the Soviet Union, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the Russian Republic. Not only Russians live in this country: at various times its inhabitants have included Ukrainians, Poles, Tartars, people from the Baltic, the Caucasus, Central Asia and many other places. Each name has political and historical overtones about which there is passionate disagreement among scholars, politicians, journalists and ordinary people.There is a particular problem about how to name the state based on the medieval city of Kiev. Most Russians call it Kievan Rus and believe that their modern state is its direct descendant. That is something that many Ukrainians vehemently deny. They call the city Kyiv, and insist on the Ukrainian spelling of other proper names too. I have tried to use whichever spelling seemed appropriate to the historical period. But many people will inevitably disagree with me.Part of the book that follows is an attempt to explain why these differences are so important. I apologise for nevertheless finding it simplest to use the words Russia, Russian and Kiev for much of the time.*In transcribing Russian words into English, I have deliberately avoided the standard scholarly systems. I have tried instead to make things as easy as may be for the non-Russian speaker (Russian speakers will be able to work out the original spelling for themselves).The sounds should therefore be spoken as written. Sounds that do not exist in English are represented thus: kh, sounds like ch in loch; zh sounds like ge in rouge. An e at the beginning of a Russian word is usually pronounced ye. Thus Yeltsin, not Eltsin; but Mount Elbruz, not Mount Yelbruz (because in Russian the E in this case is a different letter). While is pronounced yo. Thus Fedor is pronounced Fyodor, and I so spell it and similar names such as Semen/Semyon. Khrushchev and Gorbachev are pronounced Khrushchyov and Gorbachyov, but I have chosen to stay with the more familiar spellings.I use familiar English versions: Moscow, not Moskva; Peter, not Ptr; Alexander, not Aleksandr. But I depart from consistency when that feels best. So, for example, I prefer Mikhail to Michael.People unfamiliar with them find Russian names very hard to remember. Its almost impossible to make it easier, but it may help occasionally if you remember that between the first name and the surname in Russian comes the patronymic, which ends in -ovich/-evich for a man and -ovna/-evna for a woman. One cant distinguish in English between two men both called John Johnson. But Ivan Ivanovich Ivanov is John Johnson son of John, and Ivan Stepanovich Ivanov is John Johnson son of Stephen. It is perfectly proper to refer to someone by his or her first name and patronymic. Thus the last President of the Soviet Union and the first two Presidents of the Russian Republic could be respectfully addressed as Mikhail Sergeevich, Boris Nikolaevich and Vladimir Vladimirovich.I have spelled the last syllable of Russian names, where appropriate, as -sky. I have left Polish names ending in -ski, since that is how they are spelled in Polish.This book is too short to support scholarly notes or a bibliography. I have, however, attributed direct quotations in endnotes. And I have added a very short and personal list of books.