First published in 2021 by

Haus Publishing Ltd

4 Cinnamon Row

London sw11 3tw

Copyright David Owen, 2021

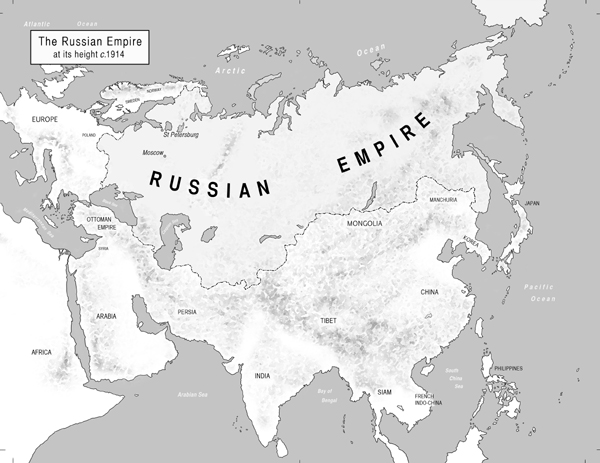

Cartography produced by Rhys Davies

Maps contain Ordnance Survey data Crown copyright and database right 2020

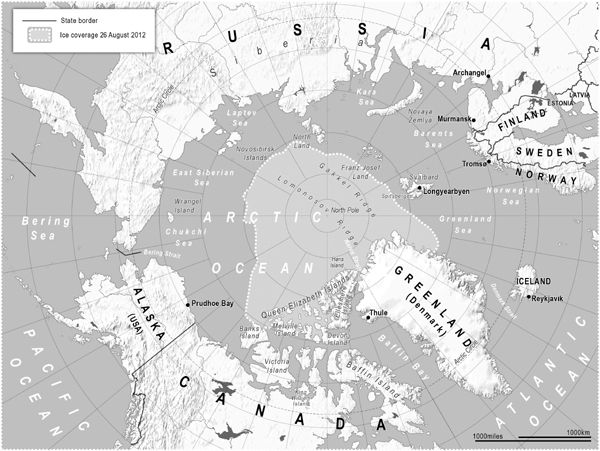

Map of the Arctic Circle reproduced with permission from Prisoners of Geography

by Tim Marshall (Elliott & Thompson, 2015), created by JP Map Graphics Ltd.

Contains public sector information licensed under the Open

Government Licence v3.0 (quotations from Hansard up to 1988)

Contains Parliamentary information licensed under the Open

Parliament Licence v3.0 (quotations from Hansard from 1989)

For quotes reproduced from the speeches, works and writings of Winston S. Churchill:

Reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown, London on behalf of

The Estate of Winston S. Churchill

The Estate of Winston S. Churchill

For the quotation from In Pursuit of British Interests: Reflections on Foreign Policy Under Margaret Thatcher and John Major:

Reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown Ltd, London, on behalf of the Estate of Sir Percy Cradock. Copyright 1997 Percy Cradock

With thanks to Esther Gilbert and the Sir Martin Gilbert estate (www.martingilbert.com) for permission to reproduce quotations from his many insightful publications on Winston Churchill

A CIP catalogue for this book is available from the British Library

The moral right of the author has been asserted

ISBN 978-1-913368-39-5

eISBN 978-1-913368-40-1

Typeset in Garamond by MacGuru Ltd

Printed in the UK by TJ Books Limited

www.hauspublishing.com

@HausPublishing

Introduction

A riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. To many, this phrase still encapsulates the challenge posed by dealing with Russia (or, as it then was, the Soviet Union). The idea persists, particularly among those with little direct experience of the country or its people, that it is difficult, if not impossible, for outsiders to understand; that it is a strange place with such a different outlook and customs that we cannot deal with it in the way we do other countries. There is no doubt that Russia can take time and effort to understand, much like any country, and particularly one so large and with such a rich history and cultural mix. Indeed, one respected commentator, the former British Ambassador to Russia, Sir Rodric Braithwaite, recently went so far as to state bluntly that:

Churchill was wrong: Russia is neither a riddle nor an enigma. Russians themselves concoct endless stories to glorify their countrys achievements and minimise its disasters and crimes. But the rest of us do much the same, as we try to explain Britains imperial history or the impact slavery still has on Americas revolutionary ideals. Russia is little harder to understand than anywhere else.

Churchill, who retained a fascination with Russia for his whole life, clearly crafted his phrase for rhetorical effect, and it is important to put it in context. What he actually said was: I cannot forecast to you the action of Russia. It is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma; but perhaps there is a key. That key is Russian national interest. Seeking to understand the UKs relationship with Russia, in both the past and the future, is something that has fascinated me throughout my life as a medical physician, a politician, a businessman, and, more broadly, as an internationalist.

According to his biographer, Churchill changed his stance towards the USSR frequently, and his explanation was not so much a lack of consistency, as is often alleged, but a consideration of what was in the historic life-interests of the British Empire at each stage.

The national interests of Britain and Russia have been intertwined for centuries, though some might argue that our periods of allegiance have been for pragmatic reasons rather than any deeper affinity. An early example is Peter the Great visiting London not for leisure or pleasure but to study shipbuilding. The royal families of the two countries over a few generations were also intertwined.

In my own lifetime, the relationship has gone from wartime allies to cyber adversaries with periods of deep mutual fear. We were arch enemies early in the Cold War but full of exuberant optimism and hope in the years following the collapse of the Soviet Union. My first recollection as a four-year-old in 1942 when refusing some food was to be told, think of the poor starving children in Russia. Yet by the time I was a student at Cambridge, a university that had earlier produced some of the Soviet Unions most successful spies, I joined the protests against the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956 and listened to the radio as the Hungarian broadcaster calling for help was suddenly cut off by the Soviet censors. Before the Berlin Wall began to be built in 1961, I crossed through Checkpoint Charlie in Berlin and drove to Communist Prague in January. In late 1962, shortly after I qualified as a doctor, I watched the Cuban Missile Crisis unfold on TV with Khrushchev versus Kennedy. I then worked as a neurologist for the psychiatrist Dr William Sargant, whose book Battle for the Mind drew on work by the and Britain. It sparked off the Greenham Common womens protest on the periphery of the former US airbase near Newbury.

Following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and as Russia emerged from the wreckage of the Soviet Empire in the early 1990s and started to carve out a new role for itself, I worked closely with Russian foreign minister Andrei Kozyrev during the early stages in my role from 1992 to 1995 as EU co-chair of the International Conference on the Former Yugoslavia working alongside the UN co-chair, first Cyrus Vance and then his successor Thorvald Stoltenberg (whose son, Jens, is the current secretary-general of NATO). I was also a member of the Carnegie Commission on Preventing Deadly Conflict from 1994 to 1999, with fellow Russian member Roald Sagdeev, Gorbachevs former scientific adviser.

Beyond the political arena, and bringing the experience I had gained as a board member of two international companies, Coats Viyella and Abbott Laboratories, I chaired the boards of three companies with Russian interests: Middlesex Holdings (later named GNE), Yukos International, and Europe Steel. This varied experience from 1995 to 2015 showed me not only the strengths of Russian medicine and science generally but also the benefits that well-run companies can bring to Russian people. I also recognised the challenges and risks of operating in what remains, certainly where major businesses are concerned, a highly politicised environment a place where business law, as generally understood, does not hold sway, where corruption is rife, and authoritarian government is the norm.