Contents

Page List

Guide

Democracy, If We Can Keep It

ALSO BY ELLIS COSE

The End of Anger: A New Generations Take on Race and Rage Colorblind: Seeing Beyond Race in a Race-Obsessed World The Best Defense

Bone to Pick: Of Forgiveness, Reconciliation, Reparation, and Revenge The Envy of the World: On Being a Black Man in America A Mans World: How Real Is Male Privilegeand How High Is Its Price? The Press: Inside Americas Most Powerful Newspaper Empires The Rage of a Privileged Class: Why Are Middle-Class Blacks Angry? Why Should America Care?

A Nation of Strangers: Prejudice, Politics, and the Populating of America

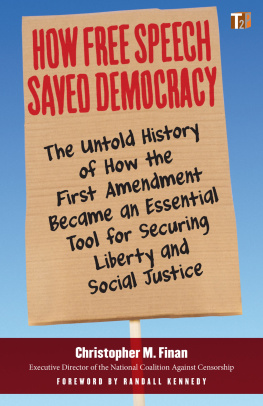

Democracy, If We Can Keep It

The ACLUs 100-Year Fight for Rights in America

Ellis Cose

For Peter Kougasian, whose intellect, talent, integrity

and wit will always be an inspiration

Contents

Introduction

I had not planned to write this book. When I became the writer in residence at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) at the invitation of Executive Director Anthony Romero, he mentioned the ACLUs upcoming centennial; but that was not to be my focus.

We had agreed that it might be an interesting experiment to embed a journalist with total editorial independence within the ACLU. I would not formally be part of the ACLU, but would be granted access to the organizations resources to inform my writing on issues related to its civil liberties mission. I had two book projects in mind. One would look at the evolving movement for criminal justice reform. The other would examine American entitlementsto privacy and social mobility, among other thingsand how technology affected them.

After Donald J. Trumps election, my focus began to shift. I couldnt imagine a coherent, constructive dialogue on criminal justice taking place with Trump in the White House. Also, Trump was threatening an unprecedented assault on civil liberties.

For months before he took office, Trump had promoted anti-Muslim travel restrictions. He regularly attacked the pressso distressing the Committee to Protect Journalists that the organization called out his betrayal of First Amendment values. The ACLU also was alarmed. The summer before his election, the ACLU released a study calling Trump a one-man constitutional crisis. It was clear that a clash of epic proportions loomed between the incoming president and the nations preeminent civil liberties organization. At that point, a book about the ACLU struck me as something worth doing.

As my focus shifted, I realized I would need to change my status. Writing a book about the ACLU while under the ACLUs roof (even with a signed promise of editorial independence) was journalistically fraught. After consulting with family and friends, I stepped down from that wonderfully privileged appointment to pursue this book as a fully independent project.

Democracy, If We Can Keep It is the result. I realized early on that writing a history of the ACLU would necessarily mean telling a story about the evolution of America itself.

The ACLU sprung out of a core promise that America made to its citizens. That promise, embodied in the Bill of Rights, was that America would always stand for freedom of conscience, freedom of speech, and freedom of dissent.

In the days when the republic was born, many questioned whether we even needed a Bill of Rights. Delegates to the Philadelphia Convention of 1787 explicitly voted against including one in the body of the Constitution. Why, many wondered, would Americans need protection from the institutions they themselves had created? As historian Gordon Wood put it, the adoption of the Bill of Rights was so fortuitous, so confused, and so inadvertent that it can only be regarded as a striking example of those many historical events whose monumental significance comes to transcend their petty and haphazard origins.

As a concession to certain foundersamong them George Mason and Thomas JeffersonJames Madison shepherded the Bill of Rights through the House. It was ratified in 1791. Not that anyone took the amendments very seriously at the time.

In the late 1790s, when American ships were being attacked by the French and fear of the conflict expanding was palpable, the promised rights became eminently disposable. One result was the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798.

Those laws made it easier to deport foreign dissidentsdangerous to the peace and safety of the United Statesand increased the waiting period for citizenship. They also made it a crime for journalists and others to publish writings that were false, scandalous, and malicious or that alienated peoples affections from the government. At the time, all branches of the government were controlled by Federalists. And the laws, as administered, effectively criminalized criticism of the Federalist government or of President John Adams.

Democratic-Republican Clubs, essentially debating societies, were disbanded. A number of writers and publishers were imprisoned. One pamphleteer was prosecuted for calling President Adams a monarchist and a toady to British interests.

As Robert and Marilyn Aiken describe the era: Federalist judges did not require the government to prove statements false. Malice was presumed and intent to defame was inferred from words that had a bad tendency.

When Thomas Jefferson took office in 1801, he pardoned those convicted under the Sedition Act and explained in a letter to former first lady Abigail Adams, I discharged every person under punishment or prosecution under the Sedition law, because I considered, and now consider, that law to be a nullity as absolute and as palpable as if Congress had ordered us to fall down and worship a golden image.

For the next century, many of the rights guaranteed by the Constitution were like precious heirlooms: things to be admired but not necessarily put to use. It was not until World War I that gross violations of the Bill of Rights by the federal government were seriously challenged. At that point, a movement of civil libertarians arose to insist that America obey its own Constitution.

Despite over a centurys effort devoted to cementing, codifying, and protecting those rights, today many Americans remain uncertain what those rights are and whether they should apply to all. National opinion polls routinely find that more than one-third of Americans have no idea what the Bill of Rights is or what the First Amendment protects. And to make matters even more surreal, America put in office a forty-fifth president who seems to believe much in the Bill of Rights is optional. He believes that dissent from his views is an act of treason and endorses tossing citizens out of the country for publicly criticizing him.

The year in which the ACLU celebrates its first century of existence seemed the proper time in which to publish a book that looks back on some of Americas history and that reminds us how difficult, and yet important, it has been to protect those who have the courage to stand up to the raucous, righteous, unthinking mob.

I am duty-bound to add that this is not the definitive story of the ACLU. I doubt that such a story could be contained in one volume. This book does not, for instance, tell in detail the story of the ACLU chapters and affiliatessome of which became influential enough to change national ACLU policy. Every ACLU leader since Roger Baldwin, its first executive director, has attempted to strengthen those affiliates. And over the years, the affiliates have grown from a rag-tag band of idiosyncratic, underfinanced cousins to become a force onto themselves. It would take a book just to tell their story. This is not that book.