First published in Great Britain in 2004 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

The moral right of John Hussey to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

John Hussey was born in 1933, and was awarded an OBE in 1971 for his services to British interests abroad. He has written for more than a dozen military and historical journals, and has appeared in BBC television and radio documentaries as a consultant on the First World War. He is currently the British representative on the historical committee advising the Belgian authorities on their project to restore the battlefield of Waterloo.

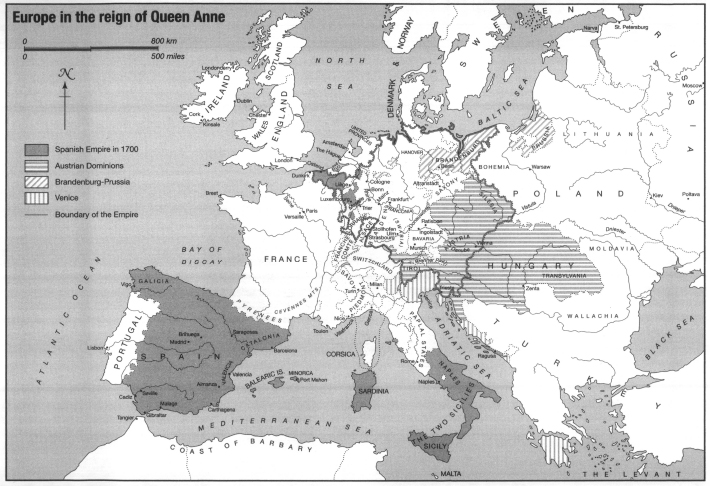

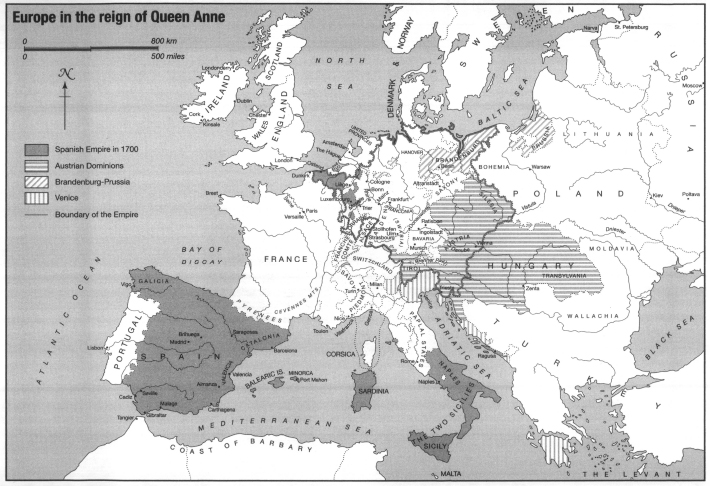

MARLBOROUGH WAS WITHOUT DOUBT one of the greatest military commanders in Anglo-American history; pre-eminent perhaps. Even the Duke of Wellington, the nearest British contender, was not called upon to operate at such a high politico-military strategic level. Eisenhower, with whom one might be tempted to compare Marlboroughs breadth and span of command, nowhere near approaches his skill as a field commander or his wide-ranging political responsibilities. On the accession of Queen Anne, Marlborough, who was already the English commander-in-chief in the Low Countries, was appointed captain general of land forces in England and Wales. In late twentieth-century terms this was the equivalent of combining the posts of c.-in-c. British Army of the Rhine and c.-in-c. United Kingdom Land Forces. In addition, Marlborough was entitled to give strategic advice to the Cabinet when English troops went to other war theatres, which today is the prerogative of the Chief of the Defence Staff. In addition to his other appointments, within weeks of becoming captain general Marlborough also secured the post of Master General of the Ordnance.

As John Hussey explains, to cover the ten great campaigns in which Marlborough served demands more space than he was given. For this masterly account he has chosen Marlboroughs 1704 campaign the brilliant march from the North Sea to the Danube, culminating in the stunning victory of Blenheim and his last campaign, which John Hussey characterizes as a masterpiece of manoeuvre.

We also get a vivid portrait of Marlboroughs development, including his early and formative years in the latter half of the seventeenth century, in which he lived two-thirds of his life. It was a century characterized by religious fear, hysteria, plots and betrayals dangers through which Marlborough trod a winding path with great skill. Although, as the author laments, there is no space for Marlboroughs personal life, we do get an insight into his abiding love for his wife, Sarah, illuminated by short extracts from his love letters.

The European political and grand strategic scene in which Marlborough operated is skilfully covered, as are the constraints of war practised at the time an era of much change both tactically and operationally. The author draws attention to the flaw in Clausewitzs analysis of warfare of the period: by hardly mentioning Marlborough, he overplays the conservatism of commanders at the tactical and operational level of war in the period between Gustavus Adolphus and Frederick the Great. By this oversight Clausewitz shows himself to be bounded by his own introverted Prussian experience.

John Hussey also provides an excellent rsum of the contemporary government machinery for administering the Army and managing the war. As he explains, Queen Annes army until 1707 consisted of three armies: English, Scottish and Irish. Up to that time Scottish and Irish regiments were transferred to the English establishment to serve abroad. Only in 1707, at the Union of Parliaments, did the British Army emerge from the combination of the Scottish and English establishments; the Irish being left separate. So, as he points out, in the first years of Annes reign it is correct to call the army overseas English, a distinction the French maintained until the twentieth century, and one which is used in this book.

We also get a very informative section on tactics, and how Marlborough surprised the French by his unorthodox deployments on the field of battle. By the early eighteenth century French military practice, as so often happens in successful armies, had ossified. Their commanders had failed to modify their tactics to meet the challenges brought about by new technology in weaponry; for example, improvements in the design of muskets.

John Hussey also challenges the view of eighteenth century warfare being frozen into total immobility by fortification and logistics, a perception partly fostered by Clausewitz, through his examination of Marlboroughs method of command and logistical skill. By caring for his men on the long march from the Low Countries to the Danube, the furthest the English had marched from a base since the Black Princes Spanish expedition over three centuries earlier, Marlborough showed that an eighteenth-century army could cover great distances and still arrive on the battlefield fit to fight.

We are reminded of the limitations of contemporary maps, and hence the careful and painstaking reconnaissance necessary to establish what routes existed, and even in which direction streams and minor rivers flowed. The staff work needed was all the more remarkable when one bears in mind how much of it was done by Marlborough himself. A staff system as we understand it did not exist.

This was an age when a successful commander had to spend an inordinate amount of time immersed in minor details, to a degree that a Montgomery, or a Patton, or most modern generals would not countenance. By the twentieth century highly trained and efficient staffs in most armies had relieved the commander of much of this time-consuming effort, allowing him to stand back and view the big picture. In Marlboroughs day a commander often stood or fell by the quality of his own staff work, and in this as in so many other respects Marlborough was a master.

He was truly a great commander.

Lhomme le plus fatal la grandeur de la

France quon et vu depuis plusieurs sicles

Il avait, par-dessus tous les gnraux de son

temps, cette tranquillit de courage au milieu du

tumulte, et cette srnit dme dans le pril

que les Anglais appellent cold head, tte froide.

VOLTAIRE Sicle de Louis XIV, Chapter 18

TO WRITE AN ACCOUNT of Marlborough the commander as he served through ten great campaigns would require far more space than this volume can offer. I have chosen, therefore, to concentrate on two campaigns: an expedition, and then a masterpiece of bloodless manoeuvre.