Unusually for one who has spent a lifetime in naval scientific research, Bernard Ireland has maintained a parallel enthusiasm for naval history. Over some thirty years, he has written more than two dozen books on various aspects of naval history and technology, including Warships of the Age of Sail. Now retired, he can devote more time to writing and to (too many) other interests. He lives with his wife on the Hampshire coast, pleasurably near to his adult son and daughter.

THE FALL OF

TOULON

The last opportunity

to defeat the

French Revolution

BERNARD IRELAND

CASSELL

Contents

Napoleon at Toulon, December 1793 ( Mary Evans Picture Library) |

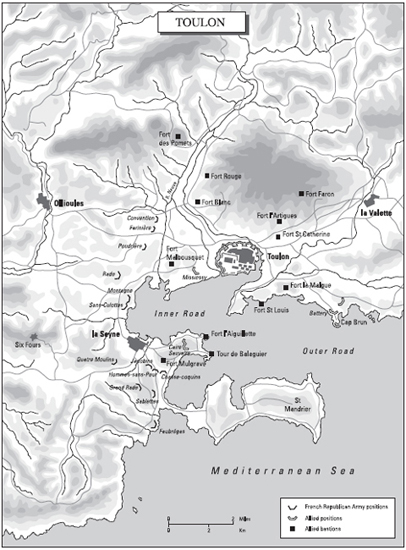

EARLY IN 1793, Revolutionary France declared war on Great Britain and, by so doing, added her to a coalition of enemies. In classic response, the Royal Navy was charged with blockading the French fleet in its various bases. Then, after only six months of hostilities, Vice Admiral Lord Hood, lying off Toulon in the Mediterranean, received a French deputation. It came with the extraordinary offer of delivering up to the British the town, its arsenal and the French Mediterranean fleet that lay within.

The background to this incredible act of treason is complex, the events that followed it heroic and ultimately tragic. Its primary cause was rooted, inevitably, in the tumultuous events of the French Revolution, its extremism and its excesses. To comprehend what happened in Toulon, it is thus necessary to have an insight into an upheaval which, far from unifying the French nation, plunged it into civil war.

A naval squadron and its dockyard are pillars of state authority and hardly likely to be surrendered meekly, without any pretence of opposition. None the less, this happened. To understand why, one needs to look carefully at the French navy of the time. Following a very respectable showing during the American War of Independence, it then withered under the destructive blast of Frances own revolution, which reached down into every stratum and facet of society and armed service.

For the complete picture, a brief portrait of the Royal Navy of the period provides not only an interesting counterpoint to that of the French navy, but goes far to explain its general attitudes. The handing over of a considerable portion of Frances battle fleet gave the British, gratis, the equivalent of a major naval victory. That they took little advantage of it is one of the most intriguing, and perhaps even now not fully explained, puzzles of naval history.

Like all good stories, therefore, the strange episode of the Royal Navy and the four-month occupation of Toulon has several threads, at first apparently only tenuously connected. Each of these has been pursued in turn in this book, tracing their individual strands until their coming together in the climactic events on the French Mediterranean coast at the end of 1793. In following these separate paths, it is inevitable that there is overlap. Some events may thus be viewed from either side of the hill, leading to apparent contradictions in national interpretation. Such is the stuff of history.

If Admiral Hood discovered (to misquote Nelson) that there were no laurels to be garnered at Toulon, the opposite was true for the young Napoleon Buonaparte, for whom the campaign was heaven-sent. Seizing the day, he was able to demonstrate for the first time those qualities that would, so shortly, catapult him to greatness.

INDISPENSABLE HELP was given by the staffs at the naval collections and archives in Gosport, Portsmouth (both at the Central Library and in the Dockyard Museum Library), in the British Library at Boston Spa and the London Library in St Jamess, the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich, the Army Collection and Museum in Aldershot and the Muse de la Marine in both Paris and Toulon.

In particular, however, the author is grateful to the staff at Fareham Public Library, who never failed to track down even the most obscure text or publication. It is reassuring to discover that, despite every government initiative, the national library system remains alive and well.

There is, of course, a huge and varying range of literature dealing with the events of those unstable times. Of all the titles consulted, those that are of most immediate value are listed in the bibliography. To all their various authors, alive or dead, named or anonymous, this author remains indebted.

Finally, as ever, he would like to recognize the support, patience and sheer hard work of his wife, for whom long-established keyboard skills had now to be allied with the mysteries of MS Word 2002.

Bernard Ireland

FAREHAM, MARCH 2005

chapter one

Revolution 178993

INSURRECTION AND REVOLUTION are conceived on a bed of discontent, for although a people may long endure injustices with little more than complaint, the effect is cumulative. As with steam leaking into a closed vessel, relief is ultimately essential if catastrophe is to be averted.

For ordinary French people in 1789 there were abundant reasons for resentment. And before them, as a perfect model of what could be done about it, stood the recent example of the United States of America. As with the French monarchy and nobility in France itself, the British rulers of colonial America had been extraordinarily unperceptive to legitimate grievances. Many of the colonists were third generation, and a completely new society had developed on the American east coast, a society which considered itself American rather than expatriate British. Government from London was regarded increasingly as out of touch and an interference in local affairs.

Having lost much of their overseas empire to the British in the Seven Years War (175663), the French saw in the American revolt a chance to embarrass their traditional enemy and, possibly, to regain territory. Beginning with shipments of weapons, French intervention extended to a significant naval presence and, ultimately, to a division of troops. For the young marquis de Lafayette, to harm England is to serve, dare I say revenge, my country.

Less defeated than wearily accepting that a continuance of the struggle was simply not worth the candle, Britain agreed to liberal terms at the Peace of Versailles, signed in 1783. Superior regular forces, directed without commitment, had proved impotent in the face of revolutionary fervour.

The American peace commissioners, while acknowledging their fledgling nations debt to France, were justly wary of the latters experienced foreign minister, who sought to make French support indispensable to the future of the United States. In reality, the British and the new Americans, despite their differences, were closely bound by family ties, and the commissioners shrewdly laid the foundations of a solid and continuing relationship.

To Great Britain, the political loss of the colonies had been a major blow but, to the poorly informed population at large, it was generally a matter of indifference. To many of those involved at an intermediate level, there was positive relief as the peace resolved a lengthy period of contention.