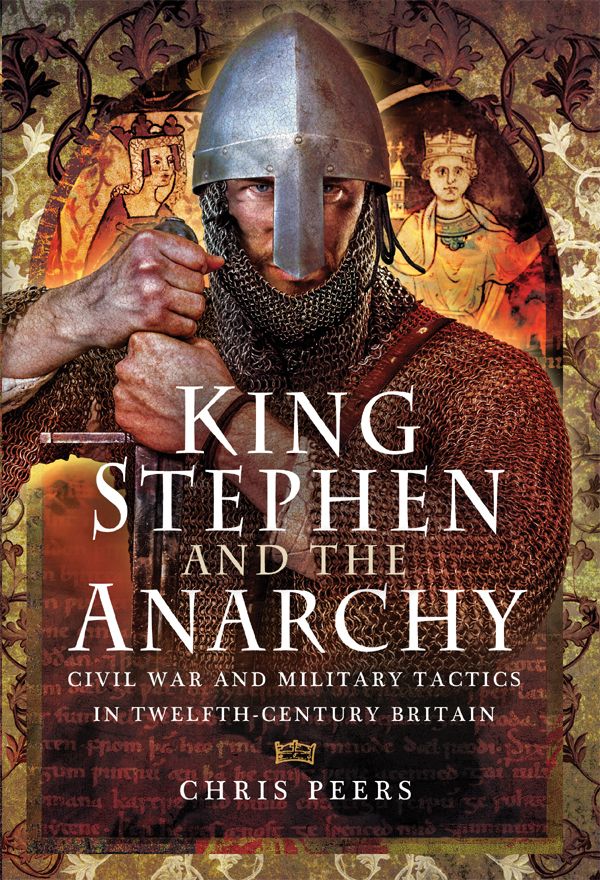

Unknown - King Stephen and The Anarchy

Here you can read online Unknown - King Stephen and The Anarchy full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, publisher: Pen and Sword, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

King Stephen and The Anarchy: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "King Stephen and The Anarchy" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Unknown: author's other books

Who wrote King Stephen and The Anarchy? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

King Stephen and The Anarchy — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "King Stephen and The Anarchy" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

King Stephen and The Anarchy

Civil War and Military Tactics in Twelfth-Century Britain

CHRIS PEERS

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

Pen and Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright Chris Peers, 2018

ISBN 978 147386 367 5

eISBN 978 147386 369 9

Mobi ISBN 978 147386 368 2

The right of Chris Peers to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

The Great Tower of Ludlow Castle in Shropshire.

The east gate of Lincoln Castle. (Flickr)

The west gate at Lincoln. (Flickr)

The west wall of Lincoln Castle.

The Observatory Tower, Lincoln Castle. (Flickr, David)

The Lucy Tower, Lincoln Castle.

Saint Georges Tower, Oxford. (Flickr, Anders Sandberg)

The original Norman motte at Oxford. (Flickr, Bernards Badger)

The side of Saint Georges Tower, Oxford, overlooking the river.

Part of the motte erected by Henry I at Bedford.

Tamworth Castle. (Flickr, Dun.can)

The Great Tower at Kenilworth in Warwickshire,

Warwick Castle. (Wikipedia Commons)

Castle Rising in Norfolk.

View from outside the earth rampart at Castle Rising.

The gatehouse at Castle Rising. (Flickr)

England in the reign of Stephen.

Medieval Orkney.

It all started as did so many things in Englands history when a group of tired and sweat-stained horsemen urged their exhausted mounts into one last uphill charge in the fading light of an October evening. Not long before that they had been facing destruction, nervously casting backward glances towards the sea which had brought them there, as the English line still stood unbroken on Senlac Hill in front of them. But now the figure of Anglo-Saxon Englands last king could be seen on the skyline ahead, hunched over his shield, fatally injured by a random arrow which had struck him in the eye. His soldiers were now too few or too demoralized to maintain the line, and as the horsemen approached they began either to run or to prepare themselves for a last stand, ready to die with their king. An army fighting in the old English tradition on foot with spear, axe and shield had been outmanoeuvred and worn down by the combination of well-organized heavy cavalry and missile troops which had already brought the Normans victory over the Byzantines and Lombards, and was soon to carry them as far as Jerusalem. It was 14 October 1066, and unlike many other so-called turning points in history, the significance of this one must have been very obvious to the men who saw it happen on that hill overlooking the English Channel. England was to change, profoundly and forever, as a result of that days deeds. What was to become known as the Battle of Senlac Hill, or Hastings, was entering its final phase, and those weary horsemen Normans, Frenchmen, Bretons, Flemings and others were about to be transformed from the desperate adventurers who had followed Duke William of Normandy across the Channel into Englands new ruling class. Not surprisingly they were convinced that the victory and the land of England had been given to them by God.

Despite their ferocity towards their enemies, and the greed for land and riches which had brought them across the sea, the Normans who led the invasion were a devoutly Christian people who had filled Normandy with splendid stone-built churches and abbeys, many of which survive to this day. Less than two centuries earlier the ancestors of many of them had been Vikings, pagan pirates who had forced the Frankish kings to grant them land in Normandy in exchange for peace. By 1066 they had enthusiastically adopted not only the faith and language of the Franks, but also the social system based on a pyramid of personal obligations, known to us today as feudalism, which had been developing since the centralized empire of Charlemagne had disintegrated in the late ninth century AD. Their leader William was Duke of Normandy, holding his duchy at least in theory as a vassal of the King of France, and presiding in his turn over a hierarchy of barons, knights, freemen and serfs, all holding their land from a superior in exchange for service of some kind, whether it be military, labour or food rents. But the Normans and their allies had retained something of their Viking ruthlessness, as the English were soon to discover. William, now King of England, dispossessed most of the native elite and distributed their lands among his own followers, imposing on this blank slate an exceptionally thorough and rigid version of the Frankish feudal system. In order to overawe the populace, he and his followers built or rather forced the common people themselves to build for them castles in every population centre and strategic location, and garrisoned them with foreign soldiers. Dissent was suppressed in a series of campaigns that even William himself, on his deathbed, acknowledged to have been excessively brutal.

But although King Harolds army had not been a match for the latest Continental techniques, England itself could not be so easily destroyed. It was a prosperous country of perhaps two million people, with a long tradition of efficient government and a thriving Christian culture in close contact with the rest of Europe. The conquerors cannot have numbered many more than 7,000, and although they retained their military traditions, their system of government and for a few centuries their French language, the process of absorbing them must have begun almost immediately after 1066. Seventy years later, when their grandchildren and great-grandchildren prepared to go to war in the upheavals of King Stephens reign which were later to become known as the Anarchy, they still looked back to the events of 1066 as their origin and their inspiration. They may even have known men who had fought at Hastings, as Stephen himself surely had as a young man, and there is no doubt that the knightly class would have identified themselves with the victors on that day. Many of them still owned land in Normandy as well as in England. But they were no longer purely Normans.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «King Stephen and The Anarchy»

Look at similar books to King Stephen and The Anarchy. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book King Stephen and The Anarchy and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.