Contents

Page List

Guide

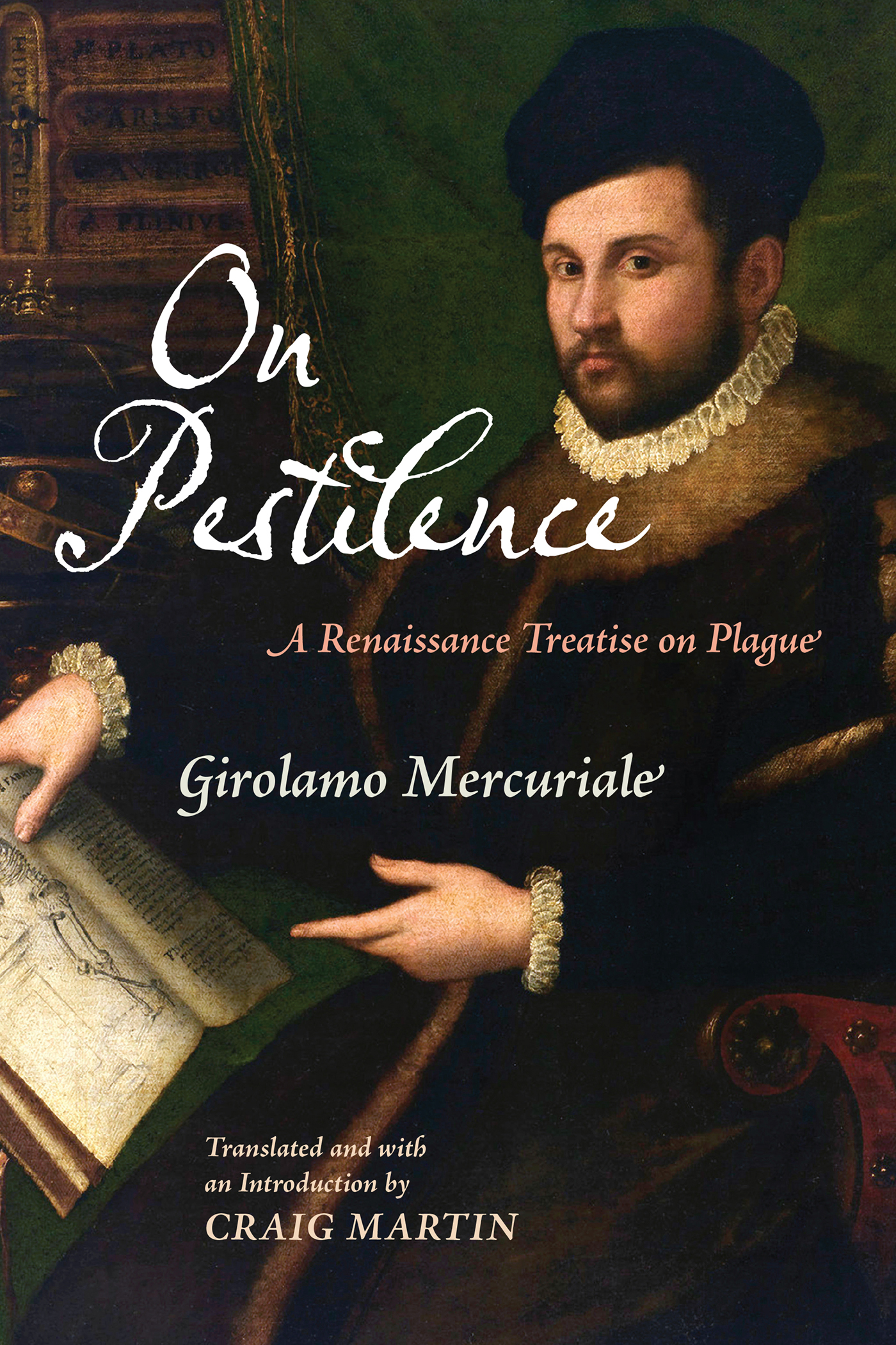

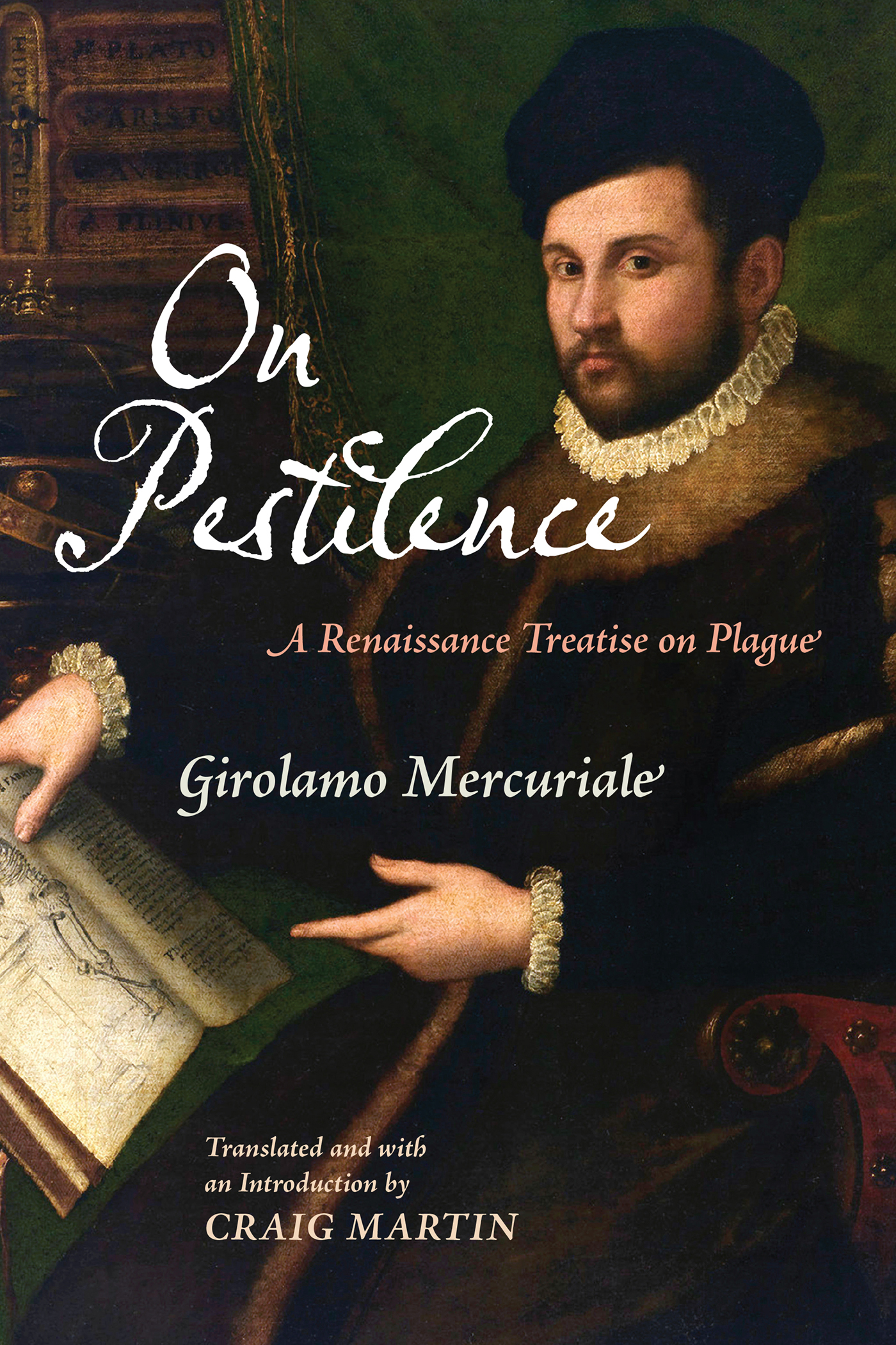

On Pestilence

On Pestilence

A Renaissance Treatise on Plague

Girolamo Mercuriale

Translated and with an Introduction by Craig Martin

Copyright 2022 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for

purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this

book may be reproduced in any form by any means

without written permission from the publisher.

Cures and remedies described in this book

are presented for historical purposes only and

should not be used as medical treatments.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10987654321

A catalogue record for this book is available

from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8122-5354-2

In memory of Russell Martin

CONTENTS

Introduction

The Plague in Venice and Girolamo Mercuriales Medical Theory and Practice

Plague struck much of northern Italy and Sicily from 1575 to 1578. It was perhaps the most significant epidemic to afflict Italy and especially Venice since the fourteenth century. Both university-trained physicians and laymen took up the task of writing these accounts.

Among those treatises written by learned elites, Girolamo Mercuriales On Pestilence (1577) holds a notorious position in the history of medicine and epidemic disease. A number of Mercuriales contemporaries blamed him for misdiagnosing the plague and demanding the removal of the quarantine at Venice, a demand that Venices rulers met. His detractors believed his actions caused the deaths of tens of thousands of Venetians. Mercuriales perceived role in exacerbating the epidemic that devastated Venices population is central to the treatises arguments and the controversies that surrounded its publication. Recent scholarship has largely interpreted the treatise as an attempt to safeguard or revive his reputation and career, a career that had been up to this point spectacular.

By 1577, Mercuriale had already developed an international reputation and a long history with Venice. A native of Forl, in the Papal States, he took his medical degree from the College of Physicians of Venice in 1555. In 1562, he went to Rome, where he served as physician to Alessandro Farnese, a cardinal and great patron of the arts. Much of his early educational and professional life circled around Venice and Padua, where he studied and collaborated with Vittore Trincavelli, a professor of practical medicine; with Gabriele Falloppio, who is best known for anatomical investigations; and with Melchiorre Guilandino (Wieland), who became prefect of the universitys Orto Botanico (Botanic Garden) and professor of pharmacological substances (known as simples). In 1569, Mercuriale was appointed ordinary professor in practical medicine at Padua.

If the goal of the treatise was to stabilize or even enhance his reputation, it likely succeeded. Despite discontent with his failure to diagnose the plague in Venice and Padua, Mercuriale remained a professor of medicine for nearly twenty-five more years, earning one of the highest salaries for his profession in all of Italy. He left Padua for the University of Bologna in 1587, accepting a lofty annual salary of 1,200 scudi, honorary citizenship, and an exemption from taxes.

Mercuriales advice to the Venetian government illustrates the dynamics of medical expertise in sixteenth-century Italy. The episode provides an example of experts inability to agree and of a divided government that opted for the advice of a prominent, well-connected physician over the recommendations of a government body, the Health Office (Provveditori alla Sanit), that was commissioned to protect Venetians lives. On Pestilence offers slightly hidden justifications and rationales, if not rationalizations, for Mercuriales diagnosis, yet its historical significance does not end there. Mercuriale put forward a deeply learned understanding of plague that employed historical analyses of epidemics and made extensive recommendations for public health measures, a relative novelty for plague treatises. While some writers of plague treatises, like Girolamo Manfredi (14301493), wrote short chapters containing advice for the prevention of the disease in cities, many did not consider the question.

Figure I. A portrait of Mercuriale by Theodor de Bry (15281598). The engraving identifies Mercuriale as professor at Padua, and the caption reads: The sun and phoenix of physicians, Girolamo Mercuriale was graced with this face. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collections (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Mercuriale was able to make more thorough historical comparisons than fourteenth- and fifteenth-century authors, in part, because he had access to a greater number of relevant primary sources, especially the writings of ancient Greek historians. Their works only began to circulate broadly in western Europe around the turn of the sixteenth century. Lorenzo Valla first translated Thucydides History of the Peloponnesian War, with its description of the Athenian plague (430426 BCE), into Latin in 1452, and it was not printed until 1483.

The craft of history underwent significant changes in the first half of the sixteenth century. Scholars increasingly used critical and comparative techniques to judge the reliability of ancient and later writings while distancing themselves from medieval understandings of the past. As Anthony Grafton writes, By 1560, both in Italy and in the north, a new ars historica had taken shape. Mercuriale honed his critical acumen on these newly available sources, contending that in order to classify and diagnose epidemics it was necessary to compare them to outbreaks of the past. Accordingly, he mined a broad range of ancient, medieval, and contemporary writings, bolstered by his own experiences, in an effort to understand the disaster that afflicted northern Italy. As a whole, the treatise is emblematic of Renaissance medical humanism, which employed comparative history and philology in its practice and theory. Mercuriale sought to redefine the concept of plague according to his reading of the Hippocratic Epidemics, while simultaneously putting forward a historical account of pestilences dependent on a panoply of descriptions of ancient epidemics, including the plague of Athens, the Antonine plague, the Justinianic plague and subsequent epidemics in the Byzantine Empire, and the medieval plagues that began in Europe in 1347 and continued throughout the early modern period.

Venices Plague of 15751577

In the three centuries that followed the plagues reentry into western Europe in 1347, epidemics with high rates of mortality recurred with varying frequency and virulence. Laboratory analysis, including that based on DNA harvested from mass graves, has shown that the bubonic plague, the disease caused by

Figure I. A portrait of Mercuriale by Theodor de Bry (15281598). The engraving identifies Mercuriale as professor at Padua, and the caption reads: The sun and phoenix of physicians, Girolamo Mercuriale was graced with this face. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collections (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Figure I. A portrait of Mercuriale by Theodor de Bry (15281598). The engraving identifies Mercuriale as professor at Padua, and the caption reads: The sun and phoenix of physicians, Girolamo Mercuriale was graced with this face. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collections (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).