A HISTORY OF PLAGUE IN JAVA, 19111942

MAURITS BASTIAAN MEERWIJK

SOUTHEAST ASIA PROGRAM PUBLICATIONS

AN IMPRINT OF CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS

Ithaca and London

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book is the product of my involvement with the ERC Starting Grant project Visual Representations of the Third Plague Pandemic (336564) in 2018. I owe a debt of gratitude to the projects principal investigator, Christos Lynteris, for his expert guidance and support. His suggestion to consider the focus of Dutch plague photography on bamboo has proven fruitful indeed. I gratefully acknowledge financial support for the publication of this book by the Association for Asian Studies and Stichting Historia Medicinae.

I wish to thank Marieke Bloembergen, Robert Peckham, Hans Pols, Susie Protschky, Ria Sinha, and the anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions at different stages of writing this book. A special thank you is owed to dear friends who helped to provide access to key sources and offered feedback on challenging sections: Angharad Fletcher, Jack Greatrex, Chi Chi Huang, Nicolo Ludovice, Maria Nicolaou, and Sarah Yu.

The staff at the Nationaal Archief and Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague, the Arsip Nasional and Perpustakaan Nasional in Jakarta, the University of Leiden Library, and the Museum Wereldculturen have been terrific in facilitating my research. Furthermore, the support of my editor Sarah Grossman and her colleagues at Cornell University Press was vital to the completion of this book.

I am deeply grateful for the continued personal and professional encouragement of family, friends, and colleagues around the world. My final thanks are owed to my parents, Paul and Erna, for a lifetime of loving support.

TECHNICAL NOTES

This book considers the Dutch response to plague in late-colonial Java. While the use of modern Indonesian spelling is generally preferable for scholarship on this region, I have chosen for the sake of clarity and consistency to adopt colonial-era spelling for Indonesian place names throughout (e.g., Soerabaja, Madioen, and Priangan). For the same reasons, most Dutch titles and organizations have been translated into English in the main body of the text with noted exceptions. Where relevant, abbreviations are used based on the original Dutch (e.g., BGD for Burgerlijke Geneeskundige Dienst and DP for Dienst der Pestbestrijding). The words improved and improvement in relation to the renovation of houses and villages in the name of plague control are used throughout as descriptive (as opposed to qualifying) terms.

The official currency in the Dutch East Indies was the guilder (f.). Financial and other numerical data presented in this book are often approximations compiled from multiple sources (see chapter 2).

Through the colonial period, Java was the most tightly controlled island in the Dutch East Indies. It boasted a large and diverse population that grew from approximately 4.5 million in 1815 to over 40 million by 1930. The colonial government was run by a corps of career civil servants: the interior government known as Domestic Governance (Binnenlandsch Bestuur, BB). Administratively, the island was divided into approximately twenty-two residenties (residencies) that consisted of several afdeelingen (districts) that were led by a resident and assistent-resident, respectively. These districts tended to overlap with historic regentschappen (regencies) that were led by a figurehead regent (regent). More locally, Dutch administrators collaborated with the (assistant) wedono (district chief) and loerah (village chief). The principalities of Djokjakarta and Soerakarta in Central Java remained nominally independent. The central colonial government was based in offices in Batavia (present-day Jakarta), its suburb Weltevreden, and the elevated cities Buitenzorg (Bogor) and Bandoeng. It was led by a governor-general appointed by the Dutch government in The Hague.

This book draws on a large number of visual materials as its historical evidence. Many of these images are available in a database compiled by the ERC-project Visual Representations of the Third Plague Pandemic and other digital repositories. I have included a selection of the images most pertinent to the arguments made in this book. Digital object identifiers and permalinks have been provided to access additional visual sources wherever possible.

Introduction

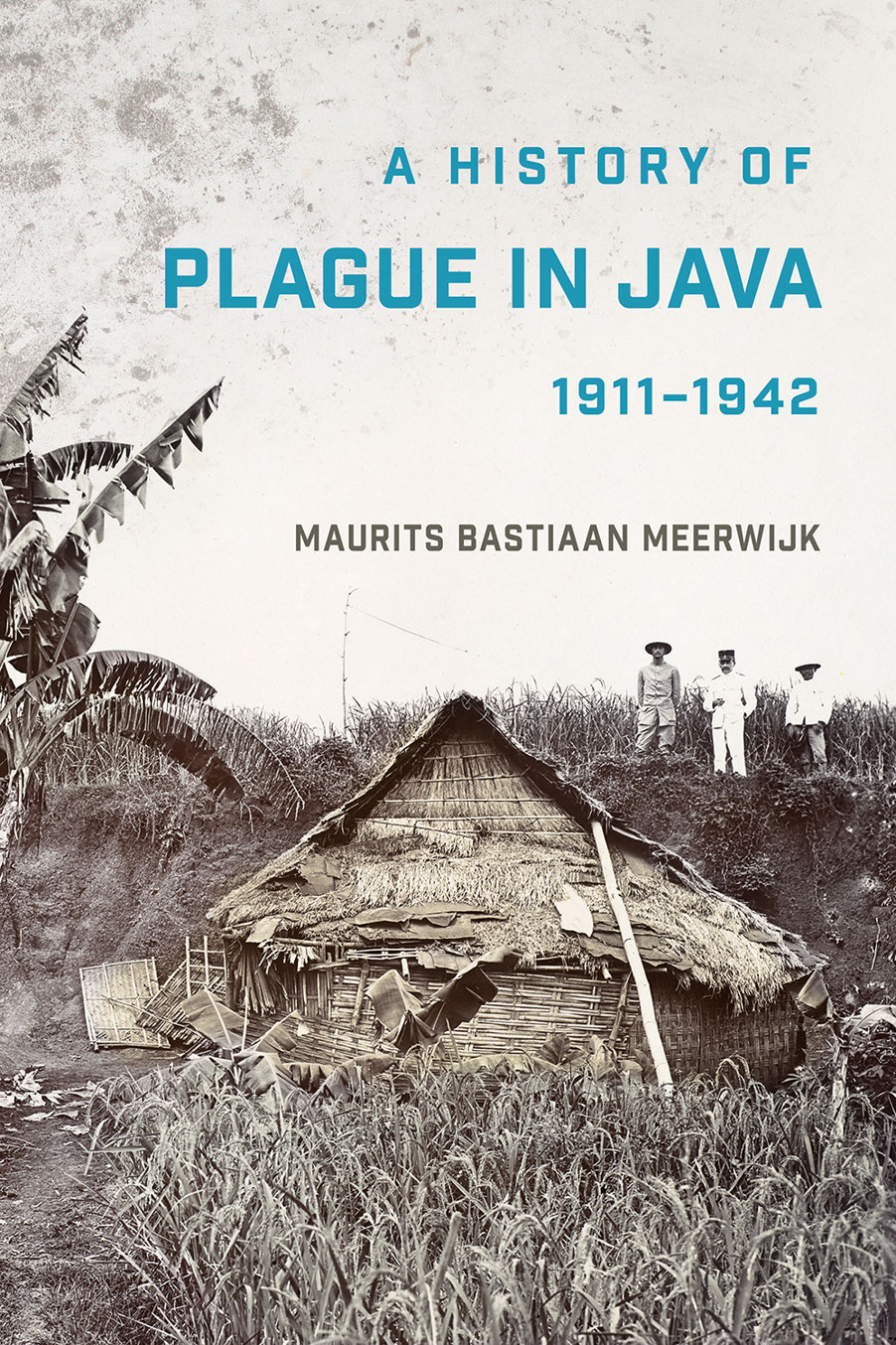

Three European men in white attire pose in a partially constructed house in Java around 1919 (figure 0.1). Two have climbed up into the beams, one emerging triumphantly through the skeleton of the roof. Below, two Javanese men in hybrid local and colonial uniform look on. The actual subject of the photographthe constructionhas been captured in its entirety. The roof dominates the image, its latticework contrasting with the sky behind. The structure is placed on a stone foundation and has wooden corner posts and joists. Most of the dwelling is drawn up of a different material, however, cheaper and readily available. Sturdy bamboo poles serve as support posts. The rafters are made of halved or split bamboo. The walls are made of a single layer of wicker bamboo mats called gedek. More pieces of bamboo are scattered in the foreground, one stalk at the base of the house revealing its hollow interior. The neatly dressed men climbing into the half-finished dwelling have something boyish about them, but the photograph nonetheless conveys a strong message regarding the prevailing race and power dynamics in the Dutch East Indies. To contemporary audiences, this would have been evident not only from the pose and positioning of the human figures, but also from the recognition that this evidently native house was no longer fully Javanese. We are witnessing a scene of home improvement in Java: one of the most invasive, sustained, and best-advertised health interventions of the Dutch colonial period that was implemented in response to the outbreak of plague in 1911.

FIGURE 0.1. Photograph of five individuals at a house being improved at Tjapar, ca. 1919. G. M. Versteeg, House at Tjapar with Home Improvement. Kastelijn, Snijders, and Fischmann with Mantri Home Improvement, ca. 1919, TM-60012999. Courtesy of the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen.

Plague is a bacterial disease that manifests predominantly in three distinct but equally graphic forms that continue to inform the pandemic imaginary. It is a zoonotic disease, strictly speaking, normally crossing over from animal reservoirs in small mammals to humans by the bite of an infected flea or by the handling of infected animals. In its most common and least deadly bubonic form victims develop acute febrile symptoms and characteristic lymphadenopathy (lymphatic swellings) in the groin, armpit, and neck: buboes. The disease overwhelms the immune system, and patients may ultimately succumb to organ failure. Bubonic plague may progress into septicemic plague, or more rarely victims develop this form through direct contact with an infected source. Here, plague bacilli infect the bloodstream and cause blood clots, tissue death, organ failure, and endotoxic shock. Finally, plague may advance to the lungs, leading to coughing, coughing up blood, and ultimately respiratory failure. This form alone is transmissible directly between humans, by breathing in highly infective particles expelled by patients through coughing or sneezing. Pneumonic plague is invariably fatal without treatment. But as with outbreaks of plague at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries elsewhere, the disease in Java was less remarkable for its mortality than for the cultural response it provoked.